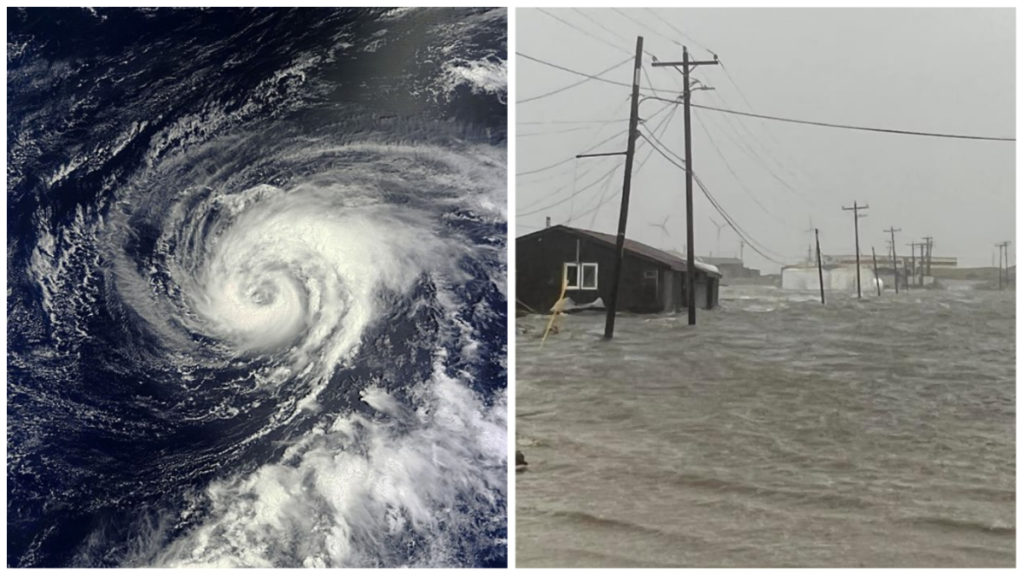

From September 16 to 18, communities across a 1,000 mile stretch of coastline in western Alaska were ravaged by the floodwaters of Typhoon Merbok. This typhoon cut off electricity and internet access, polluted the water supply, and severely damaged and destroyed houses, roads and seawalls, displacing hundreds of people in the process. Through the course of the storm, entire communities were inundated and airports were flooded, damaged and temporarily out of operation, leaving the whole region isolated and inaccessible as western Alaska can only be reached by boat or plane.

While storms are not uncommon in the region, Typhoon Merbok is the worst in recent memory — no stronger storm in the region has ever been recorded. This storm was forecast to occur earlier in the week when the Bering Sea waters were the warmest they had been in 100 years. Although the state government was aware that it was coming, nothing was done in preparation for the impending disaster. Being a region at the forefront of the effects of climate change, people in western Alaska are generally highly self-reliant, resilient and prepared for climatic shifts. However, due to the unprecedented nature of this typhoon, many elements essential to life in the area were damaged beyond repair.

Typhoon Merbok hit western Alaska at an extremely critical period of time. That week, the last barges of the year departed from villages in the region. These barges, along with air freight, are critical logistical infrastructure. Barges provide everything from food to consumer goods and construction materials to communities, and many of the items essential to repair the damages of this typhoon will now either be prohibitively expensive or unavailable until spring. It is also hunting season on which families across the region are dependent for subsistence through winter. Not only were many subsistence cabins — critical to the food security of people in western Alaska — damaged or destroyed in the storm, the time needed to repair existing housing and construct emergency shelters will leave less time for hunting, creating a potential food security crisis this winter.

Winter is also approaching fast. Freeze up is expected in about three weeks across the region, at which point many repairs will become substantially more difficult if not impossible due to both logistical and climatic challenges. Displacement and housing insecurity are also compounding issues. The Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta region already had issues with overcrowding and a lack of housing, and now many have seen their homes severely damaged or lost in the storm.

Communities in western Alaska have experienced a great deal of hardship both historically and particularly over the last few years. While the region continually grapples with the effects of climate change, it was also decimated by COVID-19 with some of the highest death and infection rates in Alaska. The superintendent of the Lower Yukon School District, Gene Stone, described the disaster caused by the typhoon as part of a year of “biblical proportions” in an interview with KYUK. “We had a fire, a 180,000 acre fire. We’ve had a crash in the fishery. I don’t want to call it famine, but people aren’t getting the fish that they’re used to eating,” Stone said. “And then we have COVID, so we have that plague, and then we have floods. We’ve kind of had everything.”

Recovery efforts and the state of Alaska’s responsibility to the region

After Governor Mike Dunleavy issued a disaster declaration on Sept. 17 — one day after the worst effects of the predicted typhoon occurred — the state government began the process of applying for federal aid. If approved, federal aid would cover up to 75% of the costs resulting from Typhoon Merbok with the state covering the additional 25%. The Alaska Community Foundation has also been successful in gathering donations with a goal of attaining $500,000. The Party for Socialism and Liberation Anchorage is encouraging Alaskans to donate a portion of their PFD, the check residents received this year from the state’s oil revenue investment fund, to the Western Alaska Recovery Fund being run by ACF.

Recovery efforts are in full swing as communities work tirelessly to repair damaged infrastructure, get electricity back to people’s homes and restore potable water. However, recovery efforts will require a great amount of monetary aid from the state and federal government, which has long neglected the needs of the largely Indigenous communities of this region. The state’s failure to prepare for disasters like this one is reflective of its larger disregard for the issues impacting rural Alaskans.

As the effects of climate change increase at an accelerated rate, Indigenous communities across Alaska are disproportionately affected by natural disasters and climatic degradation. Sea level rise and erosion pose a constant threat of displacement to communities in rural Alaska. Climate change affects salmon runs and game migration patterns, threatening subsistence hunting and fishing. It causes larger and more persistent wildfires and will only continue to fuel natural disasters like Typhoon Merbok in the future.

The lifeblood of Alaska’s economy remains vested in natural resource extraction such as oil and mining with the vast majority of this wealth concentrated in the hands of the rich. Instead of ignoring the needs of rural Alaska, future catastrophe could be avoided by using the massive wealth generated in Alaska to develop infrastructure and to plan proactively for natural disasters. With planning and infrastructure, communities will have a degree of protection. Alaskans, especially in rural communities, rely on each other when times get tough, but community and personal self-sufficiency should not be the only response.