William Massey, a founding member of The Party for Socialism and Liberation, died, April 16 at 83. Bill had been an activist in the struggle against war and racism and for socialism and liberation for 56 years.

He was born in 1934—a year of, not one, but three general strikes. At precisely the moment of his birth in early September, textile workers from South Carolina to Massachusetts were waging a bitter struggle for union recognition. He often joked that if he were a mystical man, the timing of his birth could have been taken as an omen for a life that would be spent fighting for the rights of workers and the oppressed.

Like so many that are getting involved in struggle today, Bill was not born a socialist. Though his father was a meter man for Consolidated Edison whose main privilege was to work through the depression; his mother’s family had immigrated from Ireland to escape poverty and they were nine in a five-room apartment in the Bronx; being did not determine their consciousness. Bill often quipped that two of the only things inherited from his dad were fiercely anti-communist ideas and a debilitating essential tremor. Upon his graduation from Cardinal Hayes High School in New York City, he joined the Marines and attained the rank of sergeant.

After being discharged, Bill made a brief attempt to find another side of himself by joining an Irish Christian Brothers seminary. Another of the humorous reflections on his life was that he meditated right out of there after six months. Soon he was back to his arch conservative roots by taking a job at the conservative journal National Reviewin their circulation department. There were other jobs during this period and for more than a year and a half Bill lived homeless. Something was missing, but he had no clue what it was.

In 1962, Bill was frustrated with job hunting and decided to check out a movie showing in Times Square. The film he chose was “Judgement at Nuremberg.” He was angered by the horrors of the Holocaust while simultaneously being inspired by the courage of the Civil Rights Movement fighters in the South. He hitchhiked to Albany, Georgia to participate where he ended up in jail with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.—though in a separate, but probably not equal, section.

It was James Forman, a talented organizer of the Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee and later the author of “The Making of Black Revolutionaries” who welcomed him to the movement and sent him off to be arrested at the appropriately named Crow’s drug store lunch counter with Eddie Brown, a young black man from Albany and SNCC photographer Danny Lyon. Forman did look puzzled when Bill told him he was a conservative, but there was work to be done.

Bill shared a cell with Bob Zellner, who though a white Southerner, was also a dedicated organizer with SNCC. Each time Bill met someone, his misconceptions and preconceived notions were challenged. He also met a young man, Ken Shilman, who had been in Monroe, North Carolina as a participant in the struggle to defend Robert Williams and the Black people in that community who had been fighting for the right to bear arms in order to protect themselves against racist attacks. Shilman had been drafted into the Army but then given a dishonorable discharge because as he told his commanding officers, he did not want to be part of their “murder machine.”

When asked by Bill what he thought about socialism, Shilman revealed he considered himself one. Dealing with his conservative cell mate’s skepticism, he spoke patiently of capitalism being a pyramid and described how the few had to walk all over the many to reach the pinnacle. It was the goal of socialists to turn the pyramid upside down so the majority was on top.

Bill returned to New York hungry for knowledge. Still homeless and out of work, he hung out at the New York public library. For the first time he read “The Communist Manifesto.” After so many years of speaking against its message, he realized just how reasonable a document it was and embraced its ideas. Ken Shilman invited him to a meeting of the Socialist Workers Party. Bill determined they were about overthrowing capitalism—in other words the weapon needed to flip that pyramid. He joined them and never looked away from the fight for socialism or the need for a party.

Five years after joining, he met and became the partner of a Young Socialist Alliance recruit, Beth Semmer. The two had been together as friends and comrades for 50 years at the time of William’s death. They married in 1986 and Bill made a speech that concluded with, “Not the church not the state we alone decide our fate.” Beth was talking politics, singing songs like Jimmy Roger’s “Hobo Bill’”to him and holding his hand to the end.

The couple had begun questioning the politics of the SWP in the early 1970s. They were expelled in 1974 and Bill began hunting for a new party immediately. After participating in a march against racism in Boston with Workers World Party and hearing Vincent Copeland, one of the founders of WWP, he joined them in 1975. It only took a couple of weeks to persuade Beth to follow.

In the past 56 years, Bill worked with many and learned much from those who had gone before. He learned from not only Vincent Copeland, but also Sam Marcy, Dorothy Ballan and Elizabeth Ross, some of the other founders of WWP who had also previously been in the SWP. He met a Teamster from Minneapolis who had been a leader of one of the general strikes the year Bill was born. He struggled with and learned from men who had gone to prison during WWII for their anti-war stance as well as men who ran the German blockade of the Soviet Union as partisan seaman on merchant vessels. A man who as a teenager had passed out leaflets against the Nazis and was put in a concentration camp, later escaped and walked across Europe to rejoin the resistance was someone Bill called comrade. Several times he went to meetings where Malcolm X spoke and was inspired by his powerful words of justice. He met James Baldwin and persuaded him to sign on to the defense case for students under attack in Bloomington, Indiana.

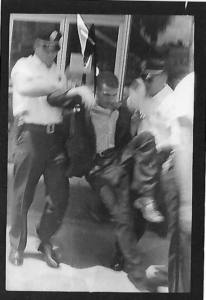

Though being arrested with Dr. King would always remain the high point of his life behind bars, he spent other time in jails over the years. Besides Albany Georgia, he was arrested in Washington, D.C., New York, NY, Chicago, twice in Seattle and once at Fort Lewis in Washington State. His favorite arrest was at a House Un-American Activity Committee hearing in D.C. He was defending the right of people to travel to Cuba and had hopped on a table to explain why he was protesting. The picture of his arrest by six policemen made the front page of several of the tabloids in New York City. One reporter stated that Mr. Massey, an unemployed dishwasher, had made the ridiculous statement that there was more freedom in Cuba than the U.S., just before he was wrestled to the ground by numerous burly policemen and carried down the steps of Congress.

Bill had a reputation for passing out the most leaflets, getting the most signatures on petitions and selling the most newspapers or magazines or whatever else he committed to doing. A picture of him passionately demonstrating to free the Cuban Five was in the newspaper Granma. That was a very special moment for Bill. He had been to Havana as a Marine before 1959. He knew why they made a revolution. While still working for National Review, he asked William F. Buckley if they had pointed out the conditions of poverty and exploitation under Batista. He truly wanted evidence to use as a conservative in arguments. Buckley said they had many times. Bill went through all the bound volumes to find the proof only to learn he had been lied to.

Bill ran for the Senate in Washington State against “Scoop” Jackson and worked with anti-war GIs at The Shelter Half coffee house near Fort Lewis. His arrest on the base happened when his anti-war group invaded by rowboat to leaflet about soldiers’ rights. He spent several years working at the Oakland Import depot unloading containers. He was proud of playing a role struggling for the rights of Black and women workers in their Teamster local.

In Bill’s last decade he struggled with severe disabilities. He was on oxygen 24/7 and was blind due to age related macular degeneration. The essential tremor he inherited from his father was particularly debilitating. Still it was not uncommon to see him in a wheel chair with an oxygen tank at a demo or a meeting to greet Cuban visitors or PSL candidate Gloria La Riva.

William took great joy in uprisings like Madison, Occupy Wall Street, the Movement for Black Lives and Fight for Fifteen, but he also knew it was essential to take the struggle of the masses to a higher level. A battle-tested leadership representing the most oppressed who are capable of facing the ruling class must be developed. True liberation will not come until the capitalist system that grinds those on the bottom of the pyramid is overthrown and destroyed. In his 70th year, William had one of his proudest moments. He was a founding member of the Party for Socialism and Liberation.

From the moment he embraced socialism, he was uncompromising, a militant, an anti-racist fighter and socialist revolutionary. Despite his body becoming ever increasingly fragile, his mind remained hungry for understanding and changing the world. The day he suffered a cardiac arrest and became unresponsive, he was asking whether the PSL was planning demonstrations to defend Syria from imperialist attacks and about the struggle against the racist police murder of Stephon Clark.

For 56 years, William Massey struggled to create a better world free of war, poverty, racism, sexism, bigotry against LGBTQ people and the assault on the environment. William Massey, Presente!