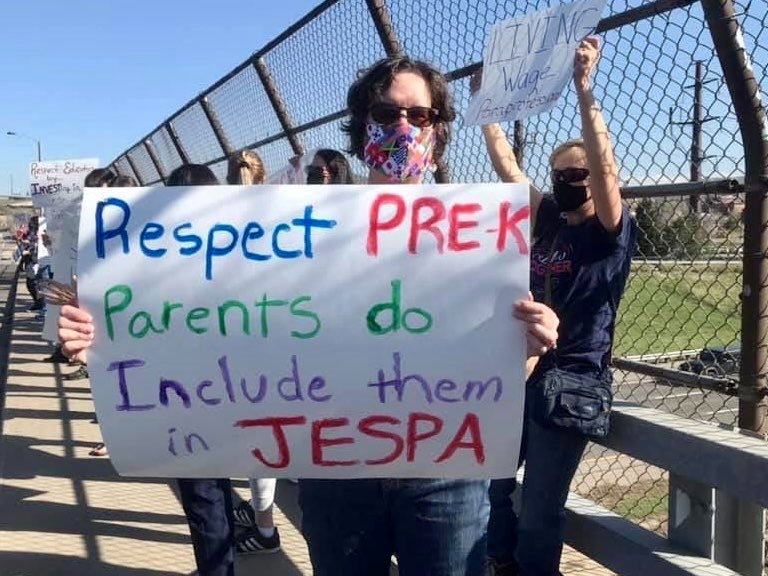

On June 4, the Jefferson County School Board in Colorado voted unanimously to recognize the union of preschool teachers across the county. One hundred and thirty-nine non-licensed preschool teachers will now be represented by the Jeffco Education Support Professionals Association, which also represents nearly 4,000 other school workers, including bus drivers, cafeteria workers and technicians (licensed teachers are represented by Jefferson County Education Association, a sister union to JESPA). This was the culmination of a campaign that began at the beginning of the year with a mass email from a new preschool teacher who was fed up with the austerity conditions faced by teachers and the lack of a voice she found in her district.

The school board vote came on the heels of an incredible 93-to-1 vote in favor of unionizing out of the 139 eligible staff. Jefferson County is a mostly suburban area west of Denver along the foothills of the Rocky Mountains.

‘I wasn’t willing to stay in that position and be quiet.‘

In January, Hannah Mauro, a new preschool teacher at Rose Stein International in Lakewood, felt she didn’t have a voice at her job. The school district was implementing changes that directly affected her and her colleagues, but these decisions had never been run past them.

Some of these changes came from years earlier. In 2019, the school board had announced a new policy that required preschool teachers to have a state teacher’s certification, which requires a degree, in order to teach. Up to that point, preschool teachers, known as Early Childhood Instructors, were not required to have one. The district initially offered assistance in receiving this certification, but during the COVID-19 crisis this aid was withdrawn.

For many older ECIs, many who had been in schools for years, it didn’t make sense to go back to school to get a certification for a job they had been doing for decades. As “at-will employees,” they could be fired at any time with few protections and little options for recourse. Tonya Toller, an instructor at Ryan Elementary, spoke of an employee who was let go the day before Christmas break. Sarah Smith, a teacher at Adams Elementary, spoke of a woman who was fired the day she returned from maternity leave.

In addition, the ECIs now had to take on the job of training new, licensed teachers, and many of the administrative tasks that had previously been handled by preschool directors — a position that did not figure into the new scheme.

Mauro had begun organizing seriously with her union after a meeting with administrators in November of 2020. It was an online meeting for the new, licensed teachers (Mauro joined alongside her licensed co-instructor), where administrators explained that the ECIs would be taking on the role of substitute teachers across the county. ECIs responded with shock and anger to this sudden demotion, and Hannah Mauro spoke up in the meeting.

After pushback from teachers, this change was never implemented. Mauro realized that she could no longer stay quiet. Using the school distribution list, she sent a mass email to all the other unlicensed instructors, saying that they were all in the same position and that organizing was the solution.

“If there’s anyone else that feels this hopeless and this small like I do, I want them to know that they’re not alone,” she said of her email. “Even if I got fired, it was worth it, because I wasn’t willing to stay in that position and be quiet.”

Tonya Toller was one of the recipients of that e-mail. She felt that the change in licensing requirements put her at the bottom of the pecking order — less a teacher in her own right, more of an assistant. She quickly signed a union card and volunteered to work on the campaign, reaching out to teachers she knew and using her contacts in the broader community to find even more to talk to. Toller said working to build the union was liberating: “Instead of going from my small little voice, we were able to go into a larger voice because we were all collaborating and working together.”

‘Yes — I want a union!‘

Within a few months, the teachers had a majority of union cards signed. According to Mauro, this should have been enough. She explained, “The board policy is super clear, and says that we don’t even need board members to approve us, and that if we have a majority of our work group who want a union that we should be considered organized.”

But the school board refused to recognize the union based on signed cards and demanded a certified election. According to Mauro, “One of the responses we got from the district was that it’s possible that we didn’t understand what we were signing, which was a huge slap in the face.”

“That we cannot read the sentence at the top: ‘Yes, I want a union,’” continued teacher Sarah Smith in a separate interview.

The teachers were disappointed in the decision, but looked forward to winning the vote. “I was angry, but I was also ready for the challenge,” explained Toller.

Smith spent this time talking to her coworkers about the issues that forming a union could help to solve. Instructors were chronically overlooked for input on the curriculum they were going to teach, and all the while they had very little job security in the face of administrative decisions. In addition, she and other organizers like Toller lobbied the board to make sure that they would respect the results of the election.

Even before the election, the other JESPA organized workers were showing the teachers a glimpse of what they could win. According to Smith, in May, JESPA had bargained for a 3% one-time bonus for their members — and fought to include the preschool teachers who were currently organizing. “You guys — this is JESPA, this is not Jeffco giving this to us,” Smith told her colleagues.

The election, which took place as an online vote, began on May 26, in the last three days of the school year. It was a hectic time for the preschool teachers. Between wrapping up their instruction and cleaning their classrooms for the summer, 93 out of 139 non-licensed preschool teachers in Jefferson County entered a vote in favor of joining JESPA. During the time between submitting their union cards and the election, support for the union had increased — from a majority to a supermajority.

While the union had already reached a majority and won on the first day of voting, the election officially closed on June 2. The very next day at a school board meeting, leaders of the campaign were prepared to make a statement in front of the board, but this was cut from the agenda without explanation. The board went ahead and called the vote, unanimously recognizing the union. Campaign leaders, like Smith, were somewhat confused by the last minute program change but thrilled that they had won their fight.

‘We moved a mountain‘

Now that these teachers have won their union, they are looking forward to contract negotiations. Teachers are working together to formulate demands by submitting ideas for the top three things they would like to see change in their workplace. Dignified wages are a vital point for preschool teachers across the county. The current starting wage for non-licensed preschool teachers in Jefferson County is $12.50/hour, a tenth of what the district superintendent makes hourly.

Teachers also want to see larger classroom budgets that cannot be taken away. According to Mauro, in the 2019-2020 school year, classrooms received $850 per classroom. The next year, each classroom got $500. Both budgets were first frozen, then dissolved, leaving instructors paying out of their pockets. While the district did receive federal relief funds, they claim the pandemic prevented them from funding the classroom budgets. Even in normal years, educators like Smith were paying $150 a month from their paychecks to stock their classrooms. They hope to solve this through the bargaining process and win victories for both themselves and their students.

Most of all, the Jefferson County preschool teachers are looking forward to having a collective voice. This voice is something that they have found among themselves over the course of the campaign. Smith had been wanting a union for most of her 23-year career in Jeffco. When Mauro sent that mass email, she was barely two years into her first teaching job, and had never been involved in labor organizing before.

“She’s the driving force of everything. She’s very humble, but it would not have happened without her,” Smith said of Mauro. “To watch her do it, and to be brave, it was empowering to us.”

“There’s a first time for everything,” Mauro said of her experience. In Smith’s opinion, “We moved a mountain.”