This statement was originally published on TheRedNation.org

Come celebrate Albuquerque’s first ever Indigenous People’s Day this Monday, Oct. 12 .

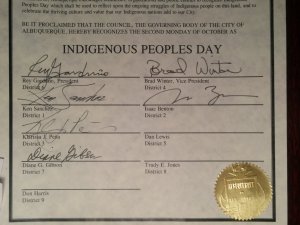

Today, Oct. 7, 2015, is historic for Indigenous peoples of Albuquerque. The Albuquerque City Council declared the celebration of Indigenous People’s Day on the second Monday of October, a day nationally recognized as “Columbus Day.”

Albuquerque is New Mexico’s largest city, and has the highest concentration of Native people in the state.

City Council President Rey Garduño-with guidance and input from The Red Nation and community organizations-wrote, sponsored, and proposed the initiative. Six councilor endorse and three abstained. Those who endorsed included Garduño, Ken Sanchez, Klarissa Peña, Isaac Benton, Brad Winter, and Diane Gibson. Those against included Dan Lewis, Trudy Jones, and Don Harris.

The Red Nation sparked the campaign last February by leading an Abolish Columbus Day demonstration, in coalition with other community groups, at the steps of City Hall. Garduño spoke at February’s event, vowing support for a citywide measure.

Albuquerque’s struggle rose directly from the Native community’s demands and support from non-Native groups, not from boardrooms. Through active coalition-building and community engagement, Indigenous People’s Day is now reality. Albuquerque joins cities—such as Seattle, Minneapolis, St. Paul, Berkeley, Portland, Lawrence, and Santa Cruz—that have also declared similar celebrations.

Many Native Nations refuse to celebrate Columbus Day, and instead recognize Indigenous Peoples Day or some other variation according to their specific histories. In New Mexico, a majority of the nineteen Pueblo Nations acknowledge their own nation-specific days. For example, the Pueblo of Poajaque celebrates “to vi’ taa,” or “People’s Day.”

What the nation-wide Abolish Columbus Day city campaigns have in common is the powerful and dynamic voice of urban Native communities. According to Census numbers, about four of every five Natives live off-reservation and about 44 percent of all Natives are under the age of 25. About 55,000 thousand Native people call Albuquerque home—35,000 of which are Diné (Navajo). Also represented in the city are 291 federally recognized Native Nations. The current Native movement, with strong ties to homelands and traditions of activism, is increasingly young, urban, and diverse, and recognizes its resounding impact for all Native Nations.

Indigenous Internationalism

Indigenous People’s Day celebrations, however, are not parochial, but part of a long history of resistance, Indigenous internationalism, and solidarity with other oppressed peoples. In 1977, the International Indian Treaty Council, the international arm of the American Indian Movement, called for the global end of the celebration of Columbus Day and declared instead the International Day of Solidarity and Mourning with Indigenous Peoples. The UN Committee on Racism, Racial Discrimination, Apartheid, and Colonialism passed the resolution, with the support of many organizations, such as the African National Congress and the Palestine Liberation Organization, who recognized that the devastating legacies of European colonialism and African slavery had to be addressed in the Americas.

In 1982, Spain and the Vatican proposed a 500-year commemoration of Columbus’s voyage at the UN General Assembly. The entire African delegation, in solidarity with Indigenous peoples of the Americas, walked out of the meeting in protest of celebrating colonialism-the very system the UN was supposed to end. The commemoration was crushed, and the UN declared a celebration of the World’s Indigenous Peoples Day and the Decade for the World’s Indigenous Peoples, which began in 1994. The second Decade was declared in 2005, and the UN adopted the Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in 2007.

Despite the celebration of Indigenous People’s Day, an estimated 370 million Indigenous peoples living in some 90 countries still constitute 15 percent of the world’s poor, and one-third of the 900 million people across the globe living in extreme poverty. Indigenous peoples live in or possess some the world’s most resource rich areas, and are often victims to corporate development projects that disproportionately affect their lands and lifeways, a direct violation of their basic human rights. They are also disproportionately subject to state persecution, sexual violence, discrimination, social exclusion, poverty, and homelessness, all symptoms of ongoing colonization and corporate exploitation.

The U.S. Native Struggle

These catastrophic realities reflect the norm for Native people living in the richest and most powerful country in world history. In the U.S., a settler colonial nation-state that actively attempts to erase Indigenous histories and presence, Native peoples are subject to the highest forms of persecution and state violence, from birth to death.

One Senate report found, “[Native] children experience post-traumatic stress disorder at the same rate as veterans returning from Iraq and Afghanistan.” Another report found Native children are three times more likely to be held in juvenile detention and two times more likely to be transferred to adult prison. Seventy percent of the juvenile population committed to the Bureau of Prisons are Natives, with 31 percent of that population committed as adults. Eighty-five percent of those committed to these federal institutions come from Arizona, Montana, New Mexico, North Dakota, and South Dakota, states with high Native populations.

On any given day, one in 25 Native adults are currently imprisoned within the U.S. justice system, at rates four times higher than whites for Native men and six times higher for Native women. Law enforcement kills Native people at the highest rate of any group. Most contact with the U.S. justice system happens off-reservation in border towns.

While making up less than one percent of the U.S. population, four percent of the nation’s homeless population is Native. Two and one-half percent of unsheltered veterans are Native, and 4.8 percent of sheltered families are Native. Most of these people live in border towns.

In Albuquerque, Natives make up 13 percent of city’s chronic homeless population, while making up only 4.6 percent of the city’s total population. Native poor and homeless are frequent targets of police and community harassment and violence. Since 2010, Albuquerque law enforcement has shot 50 people, killing 28. In 2014, after a record low of homicides, the Albuquerque Police Department committed 20 percent of city homicides. New Mexico has one the highest rates of police violence, with much of it directed towards Native people.

With these grim realities in mind, the fact that Native peoples in Albuquerque have demanded and succeeded in the recognition of Indigenous Peoples Day shows the power of Native people in coalition with other oppressed groups. It is also a testament to the power of ongoing Native resistance to settler colonialism and the resiliency of Indigenous life.

More than Symbols of Oppression

Powerful voices such as Amanda Blackhorse (Diné) show the movement to abolish racist sports mascots can galvanize millions of Indigenous peoples around the world. “Any attempt to humanize indigenous people,” she writes, “is a step in the right direction.” Any attempt to celebrate the real history of Indigenous peoples is also an attempt at humanization and a step in the right direction. The mobilization of Native people against symbolic violence in imagery, holidays, and sports mascots makes visible other Native struggles.

These struggles take place daily in cities such as Albuquerque, Gallup, Farmington, and many other murderous border towns. The perpetual threat of “man camps” sprouting near intensive resource extraction areas and adversely affecting already vulnerable Native communities has a clear connection to border towns. Many border towns began as man camps and developed into settlements, whether around railroad construction or mining, or other forms of intensive capitalist development. Violence against Natives in these communities has not subsided, and is often carried out through police violence and community discrimination. In places like Gallup, since July 2013 more than 180 Native people have died unnatural deaths, due to exposure, hit-and-runs, beatings, stabbings, and other forms of violence.

These struggles over Native life, however, are directly connected to struggles over resources such as water, oil and gas, and uranium. Navajo Nation, for example, is home to two of the dirtiest coal fired power plants in the nation and numerous hydraulic fracturing projects, which have formed the largest looming methane cloud, or “hot spot” of greenhouse gases, in North America.

The devastating Gold King Mine spill, which dumped three million gallons of toxic mine waste water into the San Juan River, also shows how corporate polluters have left thousands of mines to be cleaned up by the public. These companies continue to reap huge profits, while many Navajo Nation farmers were no longer able to use the San Juan to water crops and livestock. Relief was shoddy and inconsistent by federal agencies and the Navajo Nation. No mining company has yet been held responsible for the gross contamination of an entire river basin or offered relief assistance for the contamination they caused. Instead corporations continue to pollute and Navajo people at risk. Future spills are expected.

Join Us!

This is why The Red Nation, in coalition with many groups, understands the celebration of Indigenous People’s Day must be met with serious demands to address the conditions of Native life: the end of border town violence, the eviction of corporate polluters from Native lands, and the upholding of treaty rights for Native people on- and off-reservation.

Albuquerque’s Indigenous People’s Day proclamation declares the day “shall be used to reflect upon the ongoing struggles of Indigenous peoples on this land.” As we plan to celebrate Albuquerque’s first ever Indigenous People’s Day on Oct. 12, we must reflect on the historic and ongoing struggles of Indigenous peoples, and continue to fight.

Indigenous peoples’ continued existence, however bleak, is a product of the ancestors’ resistance to colonialism and capitalism. Our future and the earth’s future depend on carrying forward this sacred duty, a duty that deserves celebration.