In this week of the 50th anniversary of the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., we are seeing an onslaught of bourgeois rhetoric decrying the uprisings that followed his assassination.

Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. once called “riots,” (which we refer to as uprisings) as the “language of the unheard.” In other words, they were the cry of communities marginalized, left behind and oppressed. After Dr. King was assassinated, the U.S. erupted in 110 uprisings across the country, ravaging many of the nation’s largest cities. Dr. King’s own words are instructive, because, despite the scale of uprisings the week after his death, this was not a new happening in urban America. In fact, the intractable racism of the North and West, which was more deeply rooted in inequalities in the labor and housing market than the de facto Jim Crow of the south, (though both were rooted in white supremacy) had created serious tactical challenges for the Black-led movement for major social change sweeping the nation.

Dr. King’s assassination was a piercing reminder of these challenges, and suggested that some methods of struggle, previously verboten, in particular armed resistance, suddenly seemed to be more appropriate. This week, the capitalist press will be filled with accounts lamenting the “riots” of the 60s, using the uprisings after Dr. King’s death as a coda for a moment where “the good 1960s” turned into the “bad” (and by this they mean far more radical) “1960s.”

Why did urban America rise up so often in the mid-1960s? The below is an excerpt adapted from the book “Shackled and Chained: Mass Incarceration in Capitalist America” that speaks to just that.

Urban uprisings and the Black liberation movement in the 1960s

In the original draft of his speech to the 1963 March on Washington, Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee Chairman John Lewis expressed the more vexing questions raised in the course of the monumental struggle against Jim Crow segregation:

“We march today for jobs and freedom, but we have nothing to be proud of, for hundreds and thousands of our brothers are not here. They have no money for their transportation, for they are receiving starvation wages or no wages at all…. What is there in this bill to ensure the equality of a maid who earns $5 a week in a home whose income is $100,000 a year?”

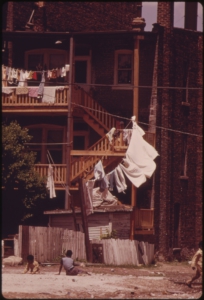

Lewis’ key point was the seemingly permanent and racist character of inequality in the United States. Even as the apartheid walls of Jim Crow came tumbling down, the majority of Blacks still lived a precarious existence in either urban slums or impoverished rural areas. This was as true in the supposedly “free” North as the South. Black people experienced extreme and disproportionate poverty, unemployment, denial of social services, red-lined neighborhoods (which they were prohibited to move into), police harassment and racist work environments.

Even where legal and formal equality was already the norm, the networks of capitalist power had already entrenched bigotry in a much more profound way. In this context, the civil rights movement began to turn decisively to challenge social and economic inequality, issues that had long been present but largely submerged under the fight for equality under the law. Inspired by the anti-colonial movements worldwide, many arrived at the conclusion that Black communities needed not just equal rights as citizens but liberation from white America.

In this expanding Black liberation movement, a range of organizations, reflecting disparate class and political backgrounds, stepped forward to offer their program for how real equality could be achieved. The Black liberation movement shifted the regional basis of protest activity away from the South to the cities and suburbs of the North and West, which had long considered themselves more enlightened than their Southern counterparts.

The problems of the urban “ghettos”—slum conditions, unemployment, job discrimination, oppressive policing and an unresponsive political system—could also be found in the South in one form or another. But because African Americans in the North already possessed many formal legal rights, including the vote, the struggle there took a radically different form. Unlike in the South, where “whites only” was open law, in the North this racist principle was reinforced in the “free” market: employers who would not hire, real estate developers who would not sell, bureaucracies that would not deliver, politicians that would not respond, courts that would not prosecute abusive police. How do you fight white supremacy in a political system that publicly disavows it? How do you fight poverty in a system that says “equal opportunity” is already the rule?

These were the hotly debated questions of the movement. “Black Power” emerged as a slogan and concept in the mid-1960s as an answer. The notion of “Black Power”—Black political, economic and cultural control over Black communities—could appeal to individuals who advocated a range of political philosophies and strategies. It had liberal and social-democratic variants, as Black representatives utilized the reorganization of voting districts spurred by the Voting Rights Act to take hold of government offices. It took more separatist expressions, as some groups sought to construct an independent Black political state in the South. Others employed the slogan primarily to build independent Black cultural and community institutions, which would help foster a united Black or pan-African identity. It could also take on varied meanings for Black socialists.

The League of Revolutionary Black Workers demanded power at the workplace and over the means of production. The Black Panther Party emphasized organized Black self-defense and the building of a revolutionary multinational united front that would ultimately overthrow capitalism.

All these political trends were responding, in one form or another, to the series of explosive urban uprisings that took place in the North, Midwest and West Coast in the late 1960s. African Americans nationwide were deeply connected to and inspired by the struggles of the South. But given the critical differences from one region to the other, the non-violent tactics and strategies that dominated at one stage of the struggle could not simply be imported and repeated.

In 1964, after the NYPD killed a Black teenager in Harlem, police charged at a protest of thousands, which set off five days of unrest in Harlem and across the city. Over 6,000 police were needed to quell the “disturbances.” In August 1965, a traffic stop in the Watts area of Los Angeles turned into a major confrontation between neighborhood residents and police. Supposedly routine traffic stops had long served as a cover for harassment, and on that night local residents attempted to intervene to prevent the arrest of a Black motorist accused of drunken driving.

Police were able to arrest the driver, along with his brother and mother, leaving the angry crowd simmering. That night, the anger boiled over into five days of “rioting.” At its peak, over 13,000 National Guardsmen were sent to Watts to restore order. Over 200 buildings were damaged in Watts, mostly white-owned businesses where usurious prices and discrimination had bred resentment. The governor’s report on the uprising stated: “We note with interest that no residences were deliberately burned, that damage to schools, libraries, churches and public buildings was minimal.”

While the “rioters” in Watts and Harlem were described as “animals” and unruly hooligans, their actions clearly had a political character. This was understood as much by the government authorities as by Black political activists. In 1967, President Johnson convened the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, or Kerner Commission, to study the rash of “riots” in the country. Although the report offered a false pathologized view of “ghetto” inhabitants, it diagnosed such problems as a result of social conditions and principally “white racism.” The report highlighted “pervasive discrimination and segregation,” which resulted in “the exclusion of great numbers of Negroes from the benefits of economic progress.”

Further, there was a “crisis of deteriorating facilities and services and unmet human needs,” in the “ghettos where segregation and poverty converge on the young to destroy opportunity.” In a poll taken by the Urban League shortly after the 1967 Detroit rebellion, at least 44 percent of respondents stated that police brutality, overcrowded living conditions, poor housing, lack of jobs and poverty had “a great deal to do” with the cause of the uprising. A poll conducted in Watts found that 64 percent of those living in the curfew zone felt that “discrimination,” and “deprivation” were key causes of the uprisings, while another poll found 58 percent of surveyed Watts residents citing “economic problems” as the central cause.

It is worth noting that the uprisings that swept the nation during the 1960s found significant, if not majority, support amongst African Americans living in affected areas. In the Newark riot of 1967, 45 percent of Black males from the ages of 15 to 35 identified themselves as rioters. In Detroit, 30 percent of Blacks surveyed were “highly sympathetic” to the riots, while in Oakland 50 percent felt riots would be “helpful.”

The uprisings or “riots” during the 1960s and early 1970s numbered in the hundreds. The Kerner Commission reported 164 “disturbances” in 1967 alone, eight of which were “major,” 33 of which were “serious.” Another study states that from 1964 to 1968 there were 329 riots “of significance.” The pattern of Black uprising was thus woven into the social experience of the period. It had a decisive impact on the mood and organizational forms within the Black communities, and within white communities whose perceptions of the events were heavily filtered through ruling-class media and politicians.