On Sept 29, 1982, about 40 officers stormed the Blues Bar in Times Square—a primarily Black and Latino gay men’s bar—and locked the doors, lining up the patrons then hitting them in the face, body and groin. As the cops shouted racist and homophobic slurs—with their guns drawn and ready to fire any moment, they threw bullets on the ground calling them “gay suppositories” that they would use to “shoot up gay asses.”

The cops trashed the bar, causing tens of thousands of dollars of damage.

None of the patrons of the bar were arrested or charged with any crime—the sole purpose of the raid was to terrorize with brutal force African American LGBTQ people. Just like today, none of the cops were charged with any crime; as the armed wing of the ruling class, they carried a pass to brutalize at will. In this case, 35 people sustained injuries and 10 went for treatment in local hospitals.

“I have never seen such destruction since my days in Vietnam. It was as if a powerful, deadly tornado wrecked total havoc within the frame of the building while allowing the outer structure to stand,” said James Credle of Black and White Men Together on the Blues Bar raid at a Congressional Hearing on Police Brutality that took place in 1983 in Brooklyn. “Blood was everywhere—splattered on the floors, the walls, the equipment—it was a total wasteland.”

Despite the ferocity of this attack by the cops and the fact that the bar was across the street from the New York Times, there was no report of this heinous racist, anti-LGBTQ raid in the ruling class media.

Moreover, despite official silence, this police attack meant more than a raid on one establishment. The Blues Bar was located in an area where working class, poor and oppressed LGBTQ people of all nationalities—primarily African American—came together to create safe havens from the hostility of daily anti-LGBTQ oppression and exclusion from downtown mafia-run bars. These downtown bars promoted white supremacy in their carding policy at the door (Blacks needed three pieces of identification to enter—a state-sponsored Jim Crow legality that ruled the few safe havens for gay people.)

Then on October 8, the police would not let up on their repression and raided the bar again. This time the community pulled together emergency planning meetings to organize a response.

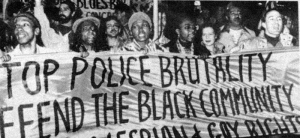

On Oct. 15, at 10 PM, more than 1000 largely Black LGBTQ people and allies descended on Times Square chanting “Hands off Blues!” and “Hey hey, Ho ho, police brutality has got to go!”

“People were so angry and so pissed off–it was a unique demonstration. People were outraged on a couple of levels: there was no media coverage and the raid was right across the street from the Times, people were outraged over the violation of a gay safe space. The police thought that the raid would make the community more invisible, but it had the opposite affect. The call was made for people to demonstrate in Times Square and people from all sectors came out to say no to racist, anti-LGBTQ police violence,” recalled Saul Kanowitz who is pictured fourth from the left in the photo of the protest and is today a member of the Party for Socialism and Liberation.

“Dykes, fags, butch, fem, women, men, blacks, whites, Hispanics, other people of color, transvestites—we were at Stonewall, standing together to say to the police: “I have pride! I have dignity! I have respect! I will not allow you to destroy or change me!” said Credle in his testimony surrounding the events around the Blues Bar raids, describing the battle cries that united the community the night of the Stonewall Rebellion 13 years earlier and which had continued up to that time.

It was a united multinational LGBTQ movement that set the stage for countering the manifestation of the anti-people offensive launched in the early 1980s. Finally, after this tremendous militant demonstration, the New York Times did dedicate an article to the outpouring of the community against police brutality.

As the onset of the AIDS crisis deepened in the years to come, the community would have to turn to deal with the reality of the crisis and to the increased bigotry and hysteria, but the spirit of the Blues Bar fightback, established in the early 1980s, reemerged later in the AIDS movements and LGBTQ struggle that was forever framed by it.