Marina Ortiz is the founder of East Harlem Preservation, which began a campaign to take down the Sims statue in 2010.

The East Harlem community was pleased to learn that New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio had (finally) agreed with their seven-year call for the removal of the J. Marion Sims statue from its location on Fifth Ave. and 103rd St. Rather than abolishing the theme of a white southern doctor who experimented on enslaved Black women without anesthesia or informed consent, however, the city has chosen to keep the Sims pedestal (and signage) in place as a clear conciliation to conservative critics.

According to a Jan. 12 press release, the City will “relocate the statue to Green-Wood Cemetery and take several additional steps to inform the public of the origin of the statue and historical context, including the legacy of non-consensual medical experimentation on women of color broadly and Black women specifically that Sims has come to symbolize. These additional steps include: add informational plaques both to the relocated statue and existing pedestal to explain the origin of the statue, commission new artwork with public input that reflects issues raised by Sims legacy, and partner with a community organization to promote in-depth public dialogues on the history of non-consensual medical experimentation of people of color, particularly women.”

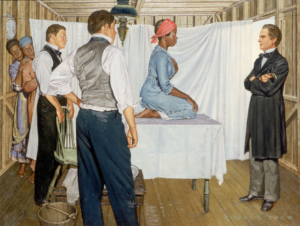

Sims has been hailed as the “father of modern gynocology” for developing a surgical method in the 19th century to treat vesicovaginal fistulas, a complication of childbirth. It took the anti-racist struggle to bring to light that this breakthrough was a result of Sims’ experimenting on enslaved African American women without consent and without anesthesia. Of the three women who are known – Lucy, Anarcha and Betsy – records show that Anarcha underwent 30 separate surgeries. Sims’ cruel experiments are documented in Harriet A. Washington’s 2006 book, “Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present.”

National campaign to remove racist monuments

The placatory “move” comes in the wake of a public debate surrounding the removal of symbols of white supremacy. Although certainly not new, the topic did gain national media attention on June 27, 2015 when activist Bree Newsome removed the Confederate battle flag from the South Carolina Statehouse—10 days after the murder of nine black parishioners in Charleston by self-avowed white supremacist Dylann Roof.

Community activists and legislators across the country stepped up their efforts even further after August 12, 2017 when James Fields Jr. —a white neo-Nazi protesting the removal of a monument to Confederate General Robert E. Lee in Charlottesville, Virginia—drove his car into a crowd of anti-racist protesters, killing 32-year-old Heather Heyer and injuring dozens more.

Sims the ‘most offensive statue’

While addressing the Charlottesville protests, Columbia, South Carolina Mayor Steve Benjamin also singled out J. Marion Sims. “I believe there are some statues on our state capitol I find wholly offensive,” he said. “The most offensive statue wasn’t a soldier, it’s J. Marion Sims, who’s considered the father of modern gynecology who tortured slave women and children for years as he developed his treatments for gynecology.”

The issue had thus broadened to the point where local opposition to symbols of white supremacy could no longer be dismissed as a matter of censorship or removing “art” for content—which had been the previous administration’s position. Mayor de Blasio then responded to the growing controversy—which included older protests against monuments to Christopher Columbus, Theodore Roosevelt, and Nazi collaborator Henri Philippe Pétain—by announcing the formation of an Advisory Commission on City Art, Monuments and Markers in August 2017.

Not surprisingly, no further public action was taken by the administration until after the general election. In mid-November 2017, the Mayor’s Commission held hearings throughout the city—during which thousands presented testimonies on monuments to Christopher Columbus, Theodore Roosevelt, and Henri Philippe Pétain. Although the debates were often contentious—with dozens of anti-racist activists, progressive educators, and radical artists sounding off against conservative historians, “traditionalists” and members of the NYPD and FDNY—not a single person testified in defense the Sims statue.

In January, 2018, the Commission presented a Report to the City of New York with recommendations. Surprisingly, or perhaps not, Mayor de Blasio then announced that only the Sims statue would be moved. The symbolic “move” was seen as a slap in the face by many who had voted for his reelection.

20,000 signed petition to take away the statue

While East Harlem residents were disheartened to learn that the administration had capitulated to a conservative political base with deep pockets, they also acknowledge and celebrate the victory of over 20,000 petitioners and activists who for years had objected to the Sims monument’s presence their neighborhood.

Still, the community maintains that Sims’ continued presence (in the form of a plaque) does a huge disservice to the neighborhood’s majority Black and Latino residents—groups that have historically been subjected to medical experiments without permission or regard for their wellbeing.

Dr. Sims is not our hero. There are many African American and Puerto Rican women (and men) who have made great medical and scientific contributions that have benefitted the East Harlem community—Dra. Helen Rodriguez-Trias, a leader in the fight against sterilization abuse, and Dr. Rebecca Lee Crumpler, the first African-American woman doctor in the US, to name a few. These are the s/heroes residents would prefer to have children learn about as they stroll in Central Park, confident in the understanding that Black Lives Matter.