Protesters led by Tenant Network RI lead a car rally to extend the Rhode Island eviction moratorium. June 22 outside Garrahy Judicial Complex. Photo courtesy of UpriseRI.com. Used with permission.

As many as 44,000 to 62,000 Rhode Island households representing as many as 100,000 to 143,000 residents may currently be at risk of eviction, according to research by HousingWorks RI. What are the roots of the housing crisis? Why have the state’s relief programs failed to divert it? And how can we fight for our right to housing?

The roots of the crisis

Before the pandemic, Rhode Island housing was deeply discriminatory and unaffordable. HWRI lays out the scope of the problem in their 2020 fact book.

In 2019, many workers already struggled to pay rent. National standards define affordable rental costs as within 30 percent of a household’s income. But 60 percent of the poorest bracket of Rhode Islanders pay upwards of 50 percent. Nowhere in the state could a household afford the average two-bedroom apartment at the median renter income of $34,000.

Black and Latino workers were most vulnerable. Sixty-seven percent of Black Rhode Islanders and 71 percent of Latino Rhode Islanders were renters, well above the national average. More than 25 percent of Latino households were overcrowded, and both groups were disproportionately employed in low-paying service, office, healthcare, and manual labor jobs.

Then the pandemic hit.

The state unemployment rate jumped to 18.1 percent in April, falling only to 12.4 percent at the end of June as phase 3 economic reopening began, leaving 68,000 people still out of work. Since the state moratorium expired in July, more than 1,200 evictions have been filed.

Despite the pandemic, property values have hit an all-time high. Rhode Island has no dedicated funding for affordable housing, and a long wait list to get a spot in existing units. And even when someone has found a new place, if they have been evicted, the court record of their eviction will show up on a background check. Potential landlords deny these applications, and many move out of state or become homeless. Meanwhile, demand for shelters has quadrupled since March, while beds statewide decreased by 142.

The failed government response

Since March, Governor Gina Raimondo has introduced several initiatives to combat the housing crisis. On paper, these measures seem monumental. But despite the state committing millions of dollars, few struggling tenants have reaped any benefit.

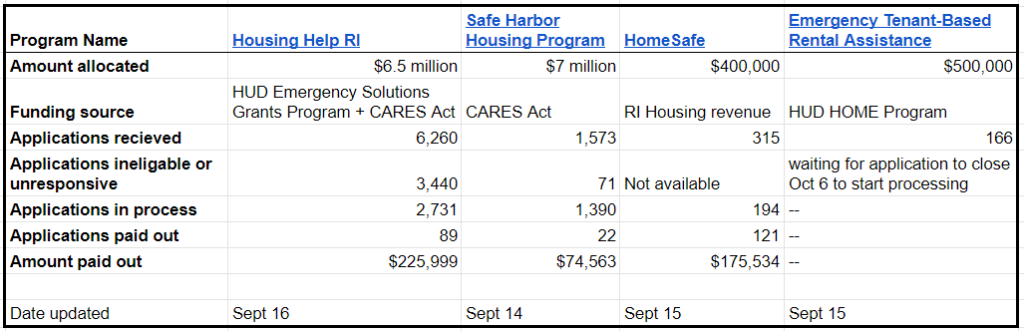

Courts were closed until the beginning of June, and Raimondo extended an eviction moratorium until the end of that month, which then expired despite calls for extension. To fend off a wave of evictions, the Rhode Island and city of Providence governments committed a collective $13.5 million to rental assistance funds between May and July. But of almost 8,000 applications submitted, only 111 applications had been fulfilled and $300,000 disbursed as of mid-September.

As shown in the graphic (Source: The Public’s Radio), the Housing Help RI and Safe Harbor Housing Programs use federal grants from the CARES Act and Housing and Urban Development. They have succeeded in processing fewer applications than HomeSafe, which is run by local community development corporations.

The failure of the program seems to be poor administration and bureaucratic barriers. Rather than hiring a dedicated staff to process applications, the state subcontracted over-burdened nonprofits. Worse yet, many applications are in limbo for lack of paperwork — either proof of hardship and finances from tenants, or tax forms from landlords.

The programs fail in part because they require landlord compliance. Rather than accepting the subsidies and waiting to receive them, a landlord is free to eject their tenants instead. Similarly, the new CDC moratorium has many exclusionary requirements, leaving landlords loopholes like terminating a month-to-month lease or informal agreement.

These, along with most other measures nationwide, are set to expire by January. By then, estimates put national rent debt at between $7.2 and 70 billion. Capitalists are concerned about long term economic effects. But 12.8 million poor and working people are worried about how they will survive.

Fighting for real relief

In every financial crisis, big businesses are bailed out while working people bear the costs. We need a people’s bailout. Rent, including rent debt, must be canceled until the pandemic is over. Empty units and houses should be turned over to unhoused people, as was recently won in Philadelphia. Small, working landlords, who rely on rent to pay their mortgages, should have their mortgage payments suspended as well. Meanwhile wealthy landlords, who sit back and collect workers’ hard-earned paychecks, should shoulder the cost of their investments.

Neither Trump nor Biden has addressed the eviction crisis, and no matter who wins, we cannot afford to wait and see what happens. The struggle for housing justice has already begun in Providence, where Tenant Network RI is organizing tenant unions to help working people stand up to their landlords. Tenant unions are winning in Minneapolis, and they can win in Rhode Island and across the country.

Just housing under socialism

When Party for Socialism and Liberation presidential candidate Gloria La Riva visited Providence, she called for rent cancellation and more: for a workers’ government, where a home would be a right. “We say, get rid of those bosses and ownership by private people. Get rid of ownership by a handful of the rich, and let us run things!”

Rent cancellation is just a glimpse of what’s possible. For the planet to survive and workers to thrive, we need socialism.