Today, the workers and oppressed people of the world stand together to celebrate the 36th anniversary of the Sandinista Revolution in Nicaragua. This article looks at the historic accomplishments of the 1979 revolution and honors the fallen Sandinista fighters who risked and sacrificed everything to free their country.

‘A Son of a Bitch, but Our Son of a Bitch’

Beginning in 1502, Christopher Columbus and the Spanish empire invaded the land that would come to be known as Nicaragua. They massacred and enslaved the indigenous resistance and underdeveloped the economy to meet the needs of the colonizer. The Niquirano, Chorotegano, and Chontal peoples valiantly resisted the conquest. Their resistance was led by the Chiefs Nicarao and Diriangán. It is from Chief Nicarao of the Niquirano nation that Nicaragua derives its name.

The Monroe Doctrine of 1823 marked the onset of Manifest Destiny and the white supremacist stance that the Caribbean and the Americas were part of the “backyard” of the United States. Filibusters (read pirates and slavers) such as William Walker sought to turn smaller, neighboring countries into English-speaking U.S. colonies. Walker organized a mercenary invasion of the country and set himself up as dictator in 1856. The U.S. military invaded and occupied Nicaragua for decades, reorienting its economy towards the needs of big business and establishing another compliant “Banana Republic.” Marine Corps Major General Smedley Butler’s summary of the true role of the U.S. military in Nicaragua and beyond is worth quoting at length, as it is still relevant eight decades later:

“I spent 33 years and four months in active military service and during that period I spent most of my time as a high class muscle man for Big Business, for Wall Street and the bankers. In short, I was a racketeer, a gangster for capitalism. I helped make Mexico and especially Tampico safe for American oil interests in 1914. I helped make Haiti and Cuba a decent place for the National City Bank boys to collect revenues in. I helped in the raping of half a dozen Central American republics for the benefit of Wall Street. I helped purify Nicaragua for the International Banking House of Brown Brothers in 1902-1912. I brought light to the Dominican Republic for the American sugar interests in 1916. I helped make Honduras right for the American fruit companies in 1903. In China in 1927 I helped see to it that Standard Oil went on its way unmolested. Looking back on it, I might have given Al Capone a few hints. The best he could do was to operate his racket in three districts. I operated on three continents.”

The humiliating foreign plunder inspired organized resistance, encapsulated in the popular guerrilla army of General Augusto César Sandino, who struck at the U.S. invaders wherever they could. To deal with this and future rebellions against their rule, the U.S. built a military school and trained the Nicaraguan National Guard. Anastasio Somoza Garcia—who hailed from a wealthy coffee plantation-owning family and was educated abroad in the United States—became the U.S.’s man in Nicaragua. He and his corrupt military henchmen emerged as the U.S.’s proxy rulers for the next four decades. From 1937 to 1979, the Somoza dynasty ruled over all facets of Nicaraguan politics and the economy with blood and iron. President Franklin D. Roosevelt was infamously quoted as saying that Somoza was “a son of a bitch, but he is our son of a bitch.” This quote captures the U.S.’s neo-colonial attitude toward the Caribbean, Latin America, the Middle East and beyond the length of the 19th and 20th centuries and through the present day.

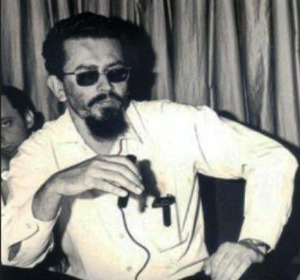

The Founding of the Sandinistas and the Leadership of Carlos Fonseca

The absolute bankruptcy of the Somoza regime bred resistance across Nicaragua. Named after the Campesino (Peasant) General Sandino—who was tricked and assassinated by Somoza in 1933—the Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN) was formed by Carlos Fonseca in 1961. The FSLN was both an urban and a rural guerrilla army that pulled together the disparate oppressed sectors of Nicaraguan society to overthrow the hated dictator.

The leadership of the FSLN studied and taught Marxism-Leninism and coordinated its efforts to confront U.S. hegemonic interests with other liberation fronts across Central American and the Caribbean. As the ideological motor of the Sandinistas, Carlos Fonseca emphasized to the future leaders of the nation the importance of reading history and studying other national liberation struggles. Many of the original guerrilla leaders received ideological and military training in Cuba before returning to spearhead the national rebellion.

Deep in the mountains or within clandestine urban foci, Fonseca sought to convert “each military combatant into a teacher of popular education.” Fonseca forged the Sandinista ideology based upon his analysis of the tactics employed by Sandino’s popular army and his study of revolution in Russian, Cuba, Vietnam and elsewhere. As a student of Vladimir Lenin and Ho Chi Minh, he emphasized that “the revolution’s significance was not just in military victories but in its capacity to grow into columns of steeled combatants.” Known to his comrades as “the other Che,” Fonseca promised his enemies: “For every West Point you have, we will form a Chipotón,” in reference to large swaths of mountainous terrain under Sandinista control that were used as staging grounds for attacks against the National Guard. Former guerrilla and present Sandinista leader Omar Cabeza’s Fire from the Mountain: The Making of a Sandinista makes for an excellent read for those wanting a detailed narrative of the disciplined training and enormous sense of self-sacrifice imbued within each Sandinista fighter.

Repression Breeds Resistance

In 1972, an earthquake rocked Managua killing thousands and leaving most of the city homeless. Anastasio Somoza Debayle, the second son of the former dictator, was now president of Nicaragua. Even though there was a shortage of blood as a result of the natural catastrophe, Somoza sold the blood of the victims abroad, cashing in on the tragedy in the most grisly of ways. This further increased popular anger at his misrule. Fighting between the Sandinistas’ fronts and the foreign-backed National Guard raged across the country.

The Sandinistas were extremely popular and flexible. Their ability to forge alliances with Liberation Theologians and to draw recruits from an array of class backgrounds merits further study for those seeking to build an anti-capitalist organization today.

Nora Astorga—guerrilla and future Sandinista ambassador to the United Nations—was one such recruit. Born into a deeply Catholic upper-class family, Astorga became politicized by the intense segregation and racism she saw while visiting Washington, D.C., in the 1960’s. Though she was guaranteed a prosperous future as a banking lawyer in Somoza’s Nicaragua, she refused to take her place at the trough and traded her briefcase for olive green fatigues and an AK 47. On International Women’s Day, she formed part of a kidnapping team that made international headlines when they abducted General Reynaldo Perez Vega or “El Perro” (the Dog), a CIA operative and Somoza’s second in command. Astorga lured Vega into a trap, where he was ambushed and held so he could be exchanged for FSLN political prisoners.

After the Sandinistas took power, Astorga—like Che Guevara a generation before her—oversaw the trials of more than 7,500 National Guard ruffians as the old state was smashed. Astorga, Giaconda Belli, Arlen Siu, Dora Maria Tellez and other Sandinista women ensured that within the ranks of the fighting units, the Sandinista Revolution was not just anti-imperialist, but also anti-machista (anti-sexist).

Sergio Ramirez—leftist intellectual and future Sandinista vice-president of the nation—wrote Adios Muchachos (Goodbye Children) to capture the élan of the times. He wrote of the “incomparable ethics of the Sandinista recruits.” He wrote of a people who believed everything was possible, at a time when everybody was united as sister and brother against the dictatorship. He told a famous story of Leonel Rugama, a Sandinista student leader who was in charge of recovering funds to be used in the people’s struggle. After a bank robbery, his getaway car was a public bus. With over $20,000 in his pockets, he refused to take a taxi because he did not want “to squander” the organization’s precious resources. Rugama’s conviction was emblematic of the fighting Sandinista spirit. At a later date, when Rugama was surrounded by Somoza’s goons in a shootout, they pressed him to surrender. Yelling “Que se rinda tu madre” (Tell your mother to surrender), he fought to the end for the patria (homeland) he knew was possible. His last words became an immortal battle cry for his comrades.

Victory

On July 19, 1979, the consolidated resistance marched triumphantly into Managua to the cheers of hundreds of thousands and claimed Nicaragua free of tyranny. Nicaragua became a beacon of hope for poor people across the globe and within the heart of the Empire itself. The old state apparatus was destroyed. In its place, the masses built up their own institutions of power such as the People’s Army, the Sandinista Workers’ Confederation, the Association of Agricultural Workers, the Nicaraguan Students Union, the Federation of Health Workers, and the National Teachers’ Union among others. These were all popular institutions of the revolution that could be mobilized against counterrevolution. Challenging old property relations, the Sandinistas began to transition to a mixed economy nationalizing public services. The disgruntled old ruling elites fled the country. Many joined their bitter Cuban counterparts in Miami to lament their losses and to organize counterrevolution, in hopes of turning back the clock of history.

The year 1980 was dedicated to eradicating illiteracy. Tens of thousands of student volunteers traveled into the countryside to offer education to neglected families. The state banned the sexual objectification of women in the media. The Sandinista spirit of internationalism and solidarity was contagious. International brigades of volunteers, from the U.S., England and around the world, traveled to Nicaragua to make their own humble contributions to the revolution in the form of building homes, bridges and other architectural projects.

The Contra War

Nicaragua was dangerous. It was proof that an organized people could overcome centuries of colonialism, exploitation and underdevelopment. In the words of Cuban poet and singer Silvio Rodriguez:

“The grass of a continent is on fire, the borders kiss and warm up to one another. … Now the eagle (the U.S.) has its biggest pain. It is hurt by Nicaragua. The eagle is hurt by love. It is hurt that a child can safely walk to school. Because now it cannot sharpen its spurs against them.”

Ronald Reagan, the personification of U.S. dominance in Central America, could not stand to see Nicaragua progress. He oversaw policies and proxy wars that hurled Nicaragua, Guatemala and El Salvador back centuries. In Nicaragua, his administration oversaw the recruitment, training and funding of the Contras. U.S. intelligence pitted hundreds of thousands of Nicaraguans against one another, employing a mercenary army whose sole task was to wreak havoc on the population. Like Renamo in Mozambique, U.S. intelligence unleashed the terrorist Contra army on peaceful Nicaragua to undo the gains of the revolution. In an interview entitled “Reagan was the Butcher of my People,” Nicaraguan priest Father Miguel D’Escoto spoke on the wanton destruction visited on his homeland. The human toll from the death squads the U.S. military trained and oversaw defies reason. It is well-documented that Reagan’s “freedom fighters” were responsible for 70,000 political killings in El Salvador, more than 100,000 in Guatemala and 30,000 in Nicaragua.

The Contras engaged in direction assassination campaigns against literacy and health care workers, engineers and anyone dedicated to rebuilding Nicaragua. Unable to get congressional approval for the war, U.S. intelligence services resorted to facilitating the sale of crack cocaine in Los Angeles and beyond in order to raise funds for this illegal war. They also secretly sold arms to their sworn enemy Iran to raise money. This was the Iran-Contra affair. CIA officer Oliver North became the face of this horrific scandal. Neither he nor anyone ever did a day in jail for these crimes. North went on to become a celebrated author, politician and patriot.

The counterrevolution’s aim—as it has been in Cuba and Venezuela—was to wear down Nicaragua. Military and economic sabotage was designed to make life unlivable under the new classes in power. The U.S. used war, hunger, inflation, devastation and hoarding as weapons to blackmail the everyday people. The left wing of the liberation movement argued that the Sandinistas should not hold an election under these conditions with their powerful enemies bankrolling the opposition. In 1990, the former bourgeoisie—Washington’s mercenaries, who were only partially unseated from power—were able to regroup and win the presidential election behind the “liberal” candidate Violeta Chamorro.

Nicaragua today

The Sandinistas returned to power in 2006 with the reelection of Daniel Ortega. But the party and the times today are not as radical as they were two decades before. Haiti experienced a similar dynamic after the U.S. organized a coup d’etat against Aristide and his Lavalas party in 1991 and then occupied the country. Imperialism’s message was unmistakably clear: We will accept a toned-down version of the Sandinistas, but do not push too far or we will snap the whip again, as they did in the case of Haiti with another coup in 2004. The example of Haiti helps explain why Nicaragua is now more of a centrist government, retaining some of the revolutionary qualities of Sandinismo but remaining trapped in debt and the austerity programs of the IMF and the U.S. government.

As part of the general wave of anti-imperialism across Latin America and the Caribbean, Nicaragua is now part of the Venezuelan-anchored ALBA (Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of America) and uses revenues from oil sales to fund anti-poverty programs Though the counterrevolution was a immeasurable immediate setback for the fighting classes of Nicaragua, the gains of the revolution remain clear. No one can deny the historic importance and symbolism of what the Sandinistas accomplished in such a short period of time. Never again could the imperialists say that the “wretched of the earth could not seize and maintain power. The Sandinistas proved that they could, inspiring the world over! Sandino Presente! Carlos Fonseca Presente!