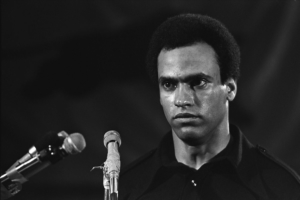

Imagine the backdrop of Huey P. Newton’s Aug. 15, 1970 speech on Women’s Liberation and Gay Liberation–just 10 days after he was released from prison. The U.S. imperialist war on Vietnam was still raging although the Tet Offensive was a great inspiration to all oppressed people. The year before Newton had announced Panthers would fight alongside the Vietnamese People’s Army. In Latin America, Socialist Salvador Allende had been elected president and Bolivia had nationalized foreign holdings. The Cultural Revolution in China was creating a beacon from Asia for revolutionaries around the world.

In the U.S., the repression against the Panthers had begun full force with the state sponsored murders of Bunchy Carter, John Huggins, Fred Hampton and Mark Clark–yet the breakfast program initiated the year before was deepening roots with the masses. The United Farm Workers union boycott of grapes was underway and wildcat and other strikes were taking place, several with majority Black leadership. Mass student protests were taking place as Nixon invaded Cambodia.

A year after the Stonewall Rebellion, a vast majority of the left was silent on gay issues or vehemently hostile to the LGBTQ community. Cuba’s isolation had not yet allowed for the revolutionary government to take on LGBTQ issues, which it later did. (Cuba of course now has become a shining example of removing an oppression that was only needed under capitalist rule, being the nation that has placed the most resources per capita in educational and anti-homophobia campaigns–the biggest push taking place during the constraints of the Special Period.)

The Soviet Union initially led the way in overturning anti-gay laws after the 1917 revolution, but the military encirclement by the imperialists and necessary dependence on skilled labor from the former ruling system put LGBTQ issues of liberation on the back burner to say the least.

So why did Huey P. Newton, the co-founder of the Black Panther Party, direct an emphatic message to the movement only a year after the Stonewall Rebellion and nascent women’s mobilizations for equality when so much else was going on?

The BPP under Newton’s leadership was taking on the development of a theoretical approach based in revolutionary Marxism that outlined the need for a united movement to fight racism and homophobia.

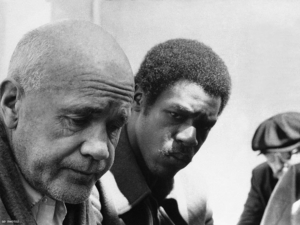

While Newton was in prison, the BPP met with French gay activist and author Jean Genet as he toured the United States appealing to audiences to build support to free the Panthers who were in prison. At his engagement at University of California, Los Angeles, an audience member shouted, “Speak about your last book!”

“No, I’m not here to talk about literature or my books. I came to defend the Black Panther Party,” responded Genet.

Revolutionaries, and exemplary ones like Newton, understand that militancy needs to backed up with vision and direction for a revolutionary movement. Newton’s leadership undertook redirecting the movement both with his solid grasp of dialectics (how things change) and sensitivity to an emerging revolutionary movement.

Lessons for the movement today

When we imagine the LGBTQ movement, we have to understand it in its totality and avoid relying on stereotyped images that the capitalist class has used to sow division.

Here’s a few reminders of the breadth of leadership:

Ortez Alderson was a leader of Third World Revolutionaries and chair of the Black Caucus of Chicago Gay Liberation who organized gay participation in the Panther Constitutional Convention in both 1970n and 1971. After breaking into a draft board to destroy files he spent a year in prison. In 1990 he died of

AIDS after being active in that movement.

A delegate to the Black Panther Convention, Kiyoshi Kuromiya was born in an internment camp during WWII; he was active in the gay rights movement prior to Stonewall. Black lesbian activist Vernita Gray helped launch Chicago’s gay liberation movement, starting the first community hotline in 1969.

The LGBTQ movement since the time of Newton’s speech has made many advances including protections in the workplace, same sex marriage and others. Yet there are setbacks like events in North Carolina and other states last year as well as numerous other battles that are taking place or about to explode anytime.

Words to describe the oppressed are a reflection of the struggle a that time–one reason the name of what was once called the Gay movement has changed many times over with each victory and each divisive strike of oppression by the ruling class.

At the time Newton was entering really unchartered territory to speak to his audience and the movement at that time about stepping up and adopting new revolutionary values to express the maximum amount of solidarity with LGBTQ people, women and other oppressed groups.

A beautiful part of his view is the notion of imagining ourselves with our allies, free of oppression, liberated, building a new society, rather than becoming entrenched in notions that might only describe our oppression now as we struggle to be free.

Newton’s vision would clearly stand in opposition to those who would compare the weight of the yoke of different oppressions, as such a view would stand in the way of all workers and oppressed coming together to tear off the yokes carried by the oppressed.

His remarkable vision embedded understanding how to win in the revolutionary process resulting in statements like this one below, which he also applied to the understanding of LGBTQ people:

Many times the poorest white person is the most racist because he is afraid that he might lose something, or discover something that he does not have. So you’re some kind of a threat to him. This kind of psychology is in operation when we view oppressed people and we are angry with them because of their particular kind of behavior, or their particular kind of deviation from the established norm.

And he cautioned those in the movement to be open to what liberation brings and not be didactic in our descriptions under oppression: “Remember, we have not established a revolutionary value system: we are only in the process of establishing it.”

Unity and solidarity as key

“When we have revolutionary conferences, rallies, and demonstrations, there should be full participation of the gay liberation movement and the women’s liberation movement,” said Newton in his speech. Today his words may seem obvious, but it took years for gender parity and LGBTQ inclusion in many movements. Two examples: among the leadership for the building of the 1993 Equal Rights March on Washington an internal struggle was waged where gender and ethnic parity was won through the intervention of revolutionary forces; only over the past decade and a half or so has it been assumed that a LGBTQ representative speak at an anti-war rally.

And he did not want to give up on moderate forces and petit-bourgeois elements that had the potential to struggle with revolutionary proletarian leadership: “Some groups may be more revolutionary than others.”

“The gay liberation front and the women’s liberation front are our friends, they are our potential allies, and we need as many allies as possible,” said Newton.

We are organizing now under different conditions especially as the ruling class’s spokesperson for division through racism, hate and bigotry, President Donald Trump, is hard at work attempting to confuse the masses who are understanding more and more the need to fight.

The call for unity–a type of unbreakable maybe even never-thought-of-before unity is in order in our organizing today. Every group oppressed under the system of profit must carry those next to them,

it’s going to be a tremendous struggle, but the prize is the same vision Newton was conveying, the liberation of humanity.