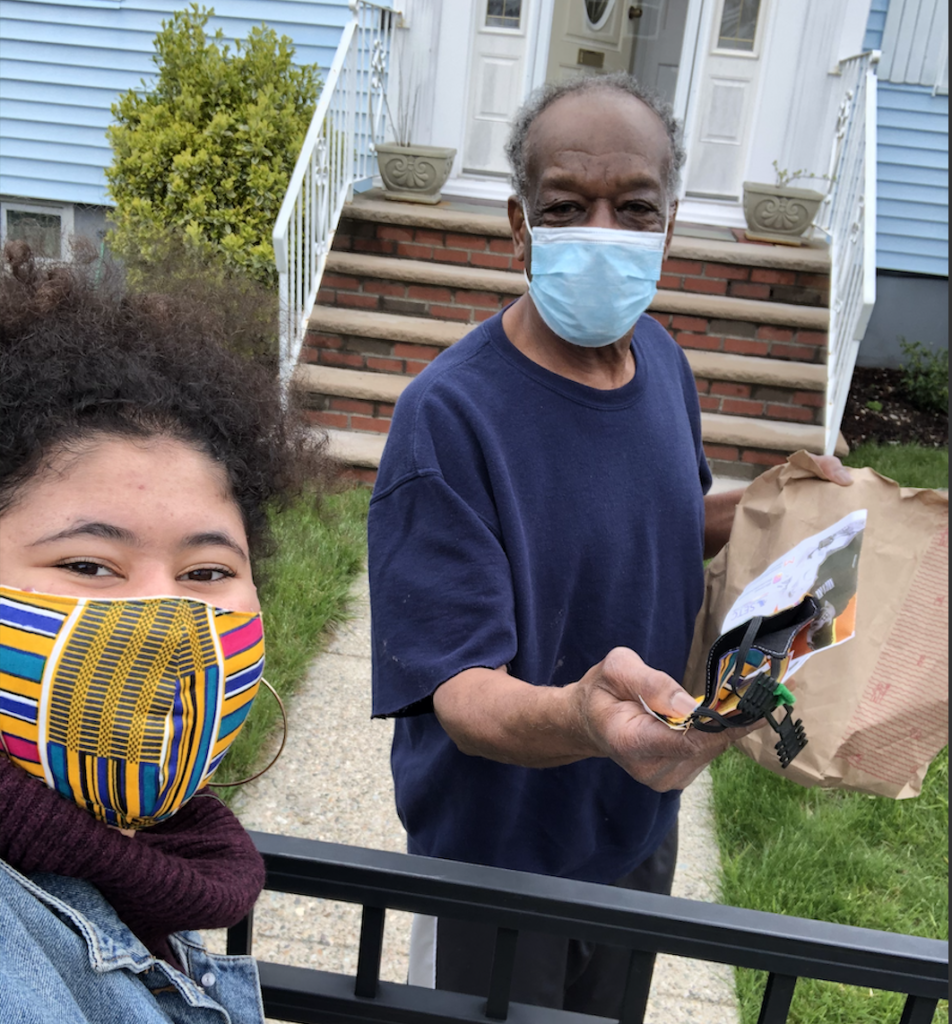

In the time of the devastating COVID-19 pandemic, the South End Technology Center @ Tent City and the Boston branch of the Party for Socialism and Liberation have partnered to produce and distribute masks and other equipment that are desperately needed by essential workers and highly vulnerable populations, including people of color, working class people and the elderly. This focus on meeting human needs follows in the footsteps of the Tech Center’s founder, Mel King, and the history of Tent City.

Mel King is a community organizer, educator, mathematician and household name in Boston. Born and raised in the South End, he is well known for his role in the fight against Boston’s Urban Renewal program in the 1960s. These infamous policies displaced working class people, especially in Black communities across the city. The South End was hit particularly hard.

Mel King and others organized to uplift the concerns of tenants and keep them informed of developments in the South End. After families’ homes were demolished to clear space for a parking garage, community members from the South End erected a temporary “tent city” and occupied the vacant lot, demanding that the land be used to house South End families. Despite being initially rebuffed by the city, the organizers continued the struggle for years until the city agreed to support the demand for affordable housing to be built on the plot. In order to honor the history of its creation, the new housing complex was named “Tent City.”

The creation of the new housing complex was a huge win for the residents. As its name reflects, the persistent organizing of community members won affordable housing, and the struggle teaches current-day organizers and community members about how to fight back against attacks on their homes and way of life.

The Tent City victory is only part of what has made Mel King so beloved in Boston. He built his career through community organizing and education. He taught math at his alma mater, Boston Technical High School until 1953 when he expanded his focus to working with youth from oppressed communities at United South End Settlements. He was fired by USES because of his advocacy for neighborhood control over urban renewal rather than governmental control. In response to protests over his termination, King was rehired as a community organizer. In 1983, he ran for mayor as the first African American finalist for the Boston mayoral seat.

King also served as a conduit through which organizers met one another as well as the community they served, just as he became a mentor to many others that were inspired to organize through his example. His face is adorned on murals and his name on fab labs throughout the city. Another contributor to his legacy is his political candor. King has consistently called attention to the systems that affect the living conditions of workers and the oppressed. In his book, Chain of Change, King writes about how the ruling class exploits oppressed nations domestically and internationally:

“They have no intention of letting go their hold of the one-way benefits that come through the colonial relationship, in which they have the upper hand. The same people who, today, are ripping off the resources of people of color in Africa and Asia, have also been busy exploiting the resources of the Black community in Boston for all these years. The controls used to maintain this relationship, both at home and abroad, are psychological and physical.”

Upon his retirement in 1997, Mel King founded the South End Tech Center in partnership with Tent City and MIT’s Center for Bits and Atoms. The goal of SETC is to expand the surrounding community’s access to science and technology. The center serves students, workers and community members access or explore technology. For example, one of the programs in the Tech Center serves formerly incarcerated people providing education around digital design and fabrication. Oftentimes, people connect to the Tech Center through word of mouth, community partnerships and out of necessity.

The Tech Center services address and alleviates some of what they refer to as both a digital divide and a fabrics divide — a divide in access to materials with which you make other things out of, and the tools to make them. Digital literacy is taught to a largely immigrant community in their native languages, and the curriculum is dictated by the students based on their needs. According to Dr. Susan Klimczak, the education organizer of the Learn 2 Teach, Teach 2 Learn program at the Tech Center, they have “one of the few [fabrication laboratories] with open access to the public.”

In L2TT2L, young people are urged to identify a problem within their community and then use the skills they learned to address that problem. Teens are taught fundamentals of applied skills in computation and physical crafting, and they then pivot to teaching the same to slightly younger teens. This is done with the help of 3D printers, laser cutters and the other electronic equipment in the fab lab. Dr. Klimczak explained that L2TT2L employs “participatory design” to empower young teachers and learners: “Young people have led the way to designing the culture of the program… Everyday, young people [give] us feedback, pick the next cohort, design the activities.”

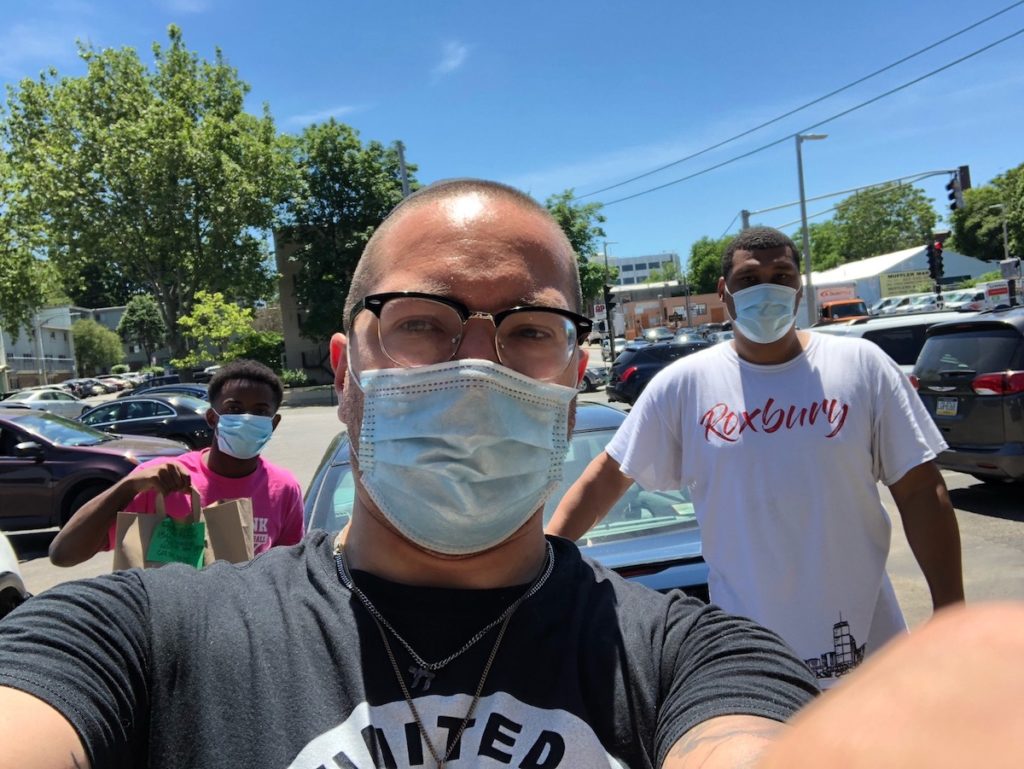

The Tech Center is a haven for many to enrich their lives, conquer fear, build relationships with other young people, explore skills and techniques that can be inaccessible, and perhaps most importantly, exercise decision-making power over what is created. After COVID-19 was recognized as a pandemic, the youth teachers in the L2TT2L rapidly strategized to start designing and producing masks. Soon thereafter, the Tech Center and PSL began their production and distribution collaboration to support and organize with vulnerable populations.

Unlike the young students at the Tech Center who immediately swung into action to shift production to meet the needs of the people, the United States government has left millions to fend for themselves. Nearly 50 million have filed for unemployment, and appropriate personal protective equipment or adequate access to healthcare services are not widely available. PPE for the People itself does not have the productive capacity to provide masks, let alone other necessities, for all of the frontline workers and vulnerable populations who need them; it is the responsibility and obligation of the U.S. government to use their powers to prepare for any COVID surge and protect the entire population.

We know that beyond COVID-19 are opportunities to prevent and prepare for the future. This crisis is opening up chances for us to combat and change the inadequacy and injustice of the government response to the pandemic. The PPE for the People campaign is an extension of the legacy and history of radical community organizing that has been built over time by Mel King and many others.