A federal judge in Oklahoma has reduced the sentence of a woman facing jail time for passing counterfeit checks in exchange for allowing herself to be sterilized. Summer Creel, who admitted to passing a check for $202.22 at Walmart in 2014, was facing a maximum sentence of 10 years in federal prison when U.S. District Judge Stephen Friot said he would consider reducing her sentence if she agreed to undergo a sterilization procedure. Judge Friot insists that it was Creel’s decision alone whether she agreed to be sterilized, despite having admitted that the length of her sentence would depend on whether she decided to undergo the sterilization procedure.

Coerced sterilization in exchange for reduced sentences is by no means unusual in the United States. In May 2017 a General Sessions Judge Sam Benningfield in Sparta, Tennessee signed a standing order to offer male inmates the option to undergo sterilization in exchange for 30 days off their sentence. Female inmates were given a less permanent option of Nexplanon, a birth control implant, which lasts several years and can cause serious side effects. This sterilization program was terminated before it began following criticism that it was coercive and violated the U.S. Constitution.

The ACLU released the following statement in response to the sterilization program in Sparta, Tennessee:

“Offering a so-called ‘choice’ between jail time and coerced contraception or sterilization is unconstitutional. Such a choice violates the fundamental constitutional right to reproductive autonomy and bodily integrity by interfering with the intimate decision of whether and when to have a child, imposing an intrusive medical procedure on individuals who are not in a position to reject it. Judges play an important role in our community – overseeing individuals’ childbearing capacity should not be part of that role.”

Though these recent occurrences of coerced sterilization are alarming, policies of forced and coerced sterilization are nothing new in the U.S. and have been ubiquitous throughout its history. Since its inception, the U.S. has committed genocide and other forms of racialized population control, and many of these policies were formally legalized in the early twentieth century during the so-called “Progressive Era.” Many states began authorizing the sterilization of “undesirable citizens,” including members of oppressed nationalities, people with disabilities and prisoners, beginning with Indiana in 1907 and eventually spreading to a total of 33 states across the U.S. Advocates of these eugenicist policies attempted to justify them by claiming that they would prevent unnecessary suffering of the “undesirables’” children and improve the gene pool.

History of forced sterilization

![A map from a 1929 Swedish royal commission report displays the U.S. states that had implemented sterilization legislation by then. By w:Harry H. Laughlin. - Betänkande med förslag till steriliseringslag / avgivet av tillkallade sakkunniga den 30 april 1929[1]Stockholm, 1929 Svenska 111 s.Serie: Statens offentliga utredningar, 0375-250X ; 1929:14, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=41364052](https://www.liberationnews.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/SOU_1929_14_Betänkande_med_förslag_till_steriliseringslag_s_57_Laughlin-300x186.jpg)

“You will be interested to know that your work has played a powerful part in shaping the opinions of the intellectuals behind Hitler in this epoch-making program. Everywhere I sensed that their opinions have been tremendously stimulated by American thought, and particularly by the work of the Human Betterment Foundation.”

Even Hitler himself praised the United States for its sterilization programs:

“I have studied with interest the laws of several American states concerning prevention of reproduction by people whose progeny would, in all probability, be of no value or be injurious to the racial stock.”

Impact on Native peoples

While eugenics became somewhat taboo after WWII due to its popularity among Nazis, forced and coerced sterilization quietly continued. During a period of time when the Bureau of Census Reports explicitly documented a steep decline in childbirth for Native American tribes, it was discovered that women who went to Indian Health Services for appendectomies were given hysterectomies without their knowledge or consent.

Records from the Government Accounting Office later verified that four out of 12 total IHS areas performed 3,406 sterilizations on Native women between 1973 and 1976 alone. Independent research indicated that as many as 25-50 percent of Native women were sterilized between 1970 and 1976. According to the GAO, contract physicians were not required to comply with federal regulations requiring that the patient give informed consent to medical procedures and many of the consent forms that were signed by patients were signed under coercion. Indigenous women all across the United States were affected; by 1968, a third of all women of childbearing age in Puerto Rico had also been sterilized.

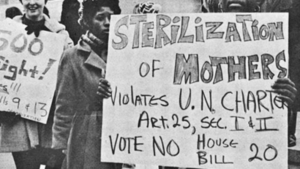

There are thousands of documented cases of forced sterilization on people who were undergoing other medical procedures from all across the country, but the practice was so common in Mississippi that civil rights activist Fannie Lou Hamer, herself a victim of forced sterilization, coined the term “Mississippi appendectomy” to describe it. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s federally funded welfare state programs encouraged the coerced sterilization of thousands of poor Black women. Many women were threatened with denial of medical care and the termination of welfare benefits if they did not “consent” to the procedure.

Sterilization abuse gained national attention in 1973 when it was discovered that two young Black girls, Minnie Lee Relf and her sister Mary Alice Relf, aged 14 and 12, were sterilized without their knowledge or consent using federal funding. Their mother was told by hospital staff that her daughters would be receiving birth control shots, and, not having the ability to read or write, she signed the forms with an “X”, believing she was consenting to temporary contraception rather than permanent sterilization. A federal lawsuit followed resulting in an order for the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare to improve its guidelines for sterilization, emphasizing the importance of informed consent.

The new guidelines were an important symbol of progress in the fight to end sterilization abuse in the United States, but the guidelines alone did not put an end to coerced sterilization. A 1974 survey of 42 large teaching hospitals across the country found that 64 percent of hospitals were in gross violation of these regulations. Fourteen of the hospitals claimed to be completely unaware that the regulations existed. Nevertheless, women and their allies continued to fight back against sterilization abuse. In 1974, Puerto Rican physician and activist Helen Rodríguez-Trías helped to form the Committee to End Sterilization Abuse, which became instrumental in this struggle. Puerto Rican national liberation organization The Young Lords Party boycotted local hospitals and even started their own clinics focused on providing safer healthcare for women in their community.

Although the victims of coerced sterilization have varied throughout U.S. history, they are all connected by claims from its advocates that sterilization is a benevolent solution to the problems their communities face. In the 1960s, advocates claimed that sterilization would help solve issues of poverty and unemployment in Puerto Rico. It was said that if women had fewer children, they would be more productive members of society, able to work more hours which, they claimed, would improve the economy . In more recent years, Benningfield, the Tennessee judge responsible for the White County Jail program, made similar comments to justify it:

“I hope to encourage them to take personal responsibility and give them a chance, when they do get out, to not to be burdened with children,” he said. “This gives them a chance to get on their feet and make something of themselves.”

Thanks to public outrage, the sterilization program in White County, Tennessee was terminated. However, the more recent news of Judge Froit in Oklahoma using reduced sentencing as an incentive to undergo sterilization in the case of Summer Creel is a reminder that coerced sterilization is not a thing of the past. It cannot be separated from its history as a tool for eugenics and genocide in the United States. Coerced or forced sterilization has been used by the ruling class for hundreds of years to exterminate and destroy communities it deems undesirable and it continues to this day. The fight against forced sterilization must continue to be a mainstay of the fight for reproductive rights.