In this age of near-total U.S. government secrecy, the truth about Washington’s actions is rarely found in the heavily redacted documents it sometimes releases in response to Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests. It often must be devined from what remains classified.

Such is the case with the 7,945 emails of former U.S. Secretary of State and now Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Clinton which the U.S. State Department has so far made public, on a rolling basis, since May 2015.

Some 391 of the emails released to date address or mention Haiti, where there was a devastating earthquake on Jan. 12, 2010, and presidential elections in November 2010 and March 2011.

Most of the emails—many heavily redacted—are terse communications between Clinton and her staff (the majority from the latter) and are often just the sharing of press reports.

The most telling and analyzed email so far is a long report from the Clintons’ daughter, Chelsea. It is undated but clearly written to Hillary and Bill (and three Clinton aides) sometime in early 2010 shortly after the earthquake. The seven-page letter harshly criticizes the earthquake response of the United Nations (UN) and international non-governmental organizations (INGOs), noting that the “incompetence is mind numbing,” that “Haitians want to help themselves and want the international community to help them help themselves,” and that “there is NO accountability in the UN system or international humanitarian system (including for/among INGOs).” Chelsea Clinton wrote that the “UN people I encountered were frequently out of touch … , anachronistic in their thinking at best and arrogant and incompetent at worst” and that “Haitians in the settlements are very much organizing themselves, in part to help define their needs and then articulate them to the UN/INGO community.”

The most interesting aspect of Clinton’s Haiti emails so far, however, is what’s not there, a gap in them from Dec. 15, 2010 until Nov. 23, 2012.

What can account for the sudden 23-month break?

An educated guess would be that U.S. censors want to hide Washington’s intervention and pivotal role in determining the outcome of Haiti’s sovereign elections following the first-round polling on Nov. 28, 2010.

In December 2010, Haiti’s Provisional Electoral Council (CEP) had announced that the winners of that first round were Mirlande Manigat and Jude Célestin, the candidate of then President René Préval’s party INITE (Unity). But through the Organization of American States (OAS)—dubbed some years ago by the Cuban government Washington’s “Ministry of Colonial Affairs”—the U.S. managed to overrule Haiti’s CEP and have third-place finisher Michel Martelly replace Célestin in the runoff.

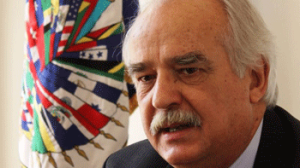

Ricardo Seitenfus, a Brazilian professor of international affairs who was then the OAS’s Special Representative in Haiti, called the foreign intervention an “electoral coup.” After publicly expressing his dismay, Seitenfus was fired.

As the democratic uprising in Egypt was erupting, Clinton traveled to Haiti on Jan. 30, 2011, to pressure Préval’s government to bow to the OAS’s override of Haiti’s sovereign electoral council. After brief defiance, Préval folded. Martelly went on to win the Mar. 20, 2011, runoff, a contest with the record lowest voter participation (less than 25%) in a presidential election not just in Haiti but in the Western Hemisphere since 1945.

Haiti’s CEP, constitutionally the “final arbiter” of any election, never agreed with the election’s results. In July 2015, the 2011 CEP’s director general, Pierre Louis Opont, publicly admitted on Haitian radio that the Haitian electoral council’s results had been changed through the intervention of Hillary Clinton, Clinton aide Cheryl Mills, and the OAS. The controversial Mr. Opont is now presiding over the current CEP, which is organizing national municipal, legislative, and presidential elections. The first round on Aug. 9 was plagued by fraud, violence, and low turnout, and is highly contested.

U.S. Ambassador Pamela White became one of the Martelly administration’s most fervent cheerleaders, despite a growing popular uprising against its corruption, electoral obstructionism, reign of impunity, and selective arbitrary repression, resulting in Prime Minister Laurent Lamothe’s resignation in December 2014. The U.S. Embassy’s strong backing of the Martelly/Lamothe regime on Clinton’s watch as Secretary of State, which ended on Feb. 1, 2013, may also explain why the emails remain classified and hence missing from the State Department’s FOIA site.

In the spring of 2011, the media organization WikiLeaks provided Haïti Liberté with 2,000 cables—classified from confidential to secret, dating from April 2003 to February 2010—which were obtained through an unauthorized leak. Haïti Liberté’s team treating the documents was disappointed to discover that there were no cables to or from the Haitian embassy in Port-au-Prince until March 2005, a full year after the Feb. 29, 2004, coup d’état against President Jean-Bertrand Aristide. This indicates that Port-au-Prince Embassy documents from April 2003 to March 2005 had a higher level of classification such as “Top Secret” or “Core Secret.” U.S. diplomatic communications in the months leading up to and immediately following the 2004 coup therefore remain secret.

Similar high secrecy around Washington’s agenda and actions in Haiti in 2011 and 2012 likely explain the abrupt end to Hillary’s Haiti emails after the November 2010 election.

So, journalists and the American public are left guessing what Ms. Clinton’s State Department was up to in Haiti after December 2010, at least until another unauthorized leak offers a real window into the inner machinations of the U.S. foreign service.