The story of Muhammad Ali’s trip to “rescue American hostages” is back in the media since the June 3 death of this unique individual: boxing’s greatest fighter, and perhaps one of the most beloved and inspiring figures of the 20th century.

President Obama’s comments on the Iraq trip were republished in a USA Today article that ran immediately following the news of the champ’s death: “We admire the man who has never stopped using his celebrity for good — the man who helped secure the release of 14 [sic] American hostages from Iraq in 1990,” wrote President Obama.

Gone but a week and Ali’s courage in the face of government opposition is quickly being re-written by the same forces that he stood up against. His legacy and courage demand that history be recounted truthfully.

I was the central organizer of Muhammad Ali’s peace delegation that traveled to Iraq in 1990, the delegation to which Saddam Hussein released 15 American hostages.

The idea for the delegation came from former U.S. Attorney General Ramsey Clark, who asked me to be the organizer of the trip on his behalf. Other anti-war activists joined us.

Unfortunately the current telling of this story largely misses or obscures the main point of Ali’s trip to Iraq, what happened there and why.

Ali’s trip to Iraq was in fact vehemently opposed by the George H.W. Bush administration. The mass media castigated and ridiculed him at the time. He went to Iraq in defiance of the U.S. government and not on its behalf.

Our delegation arrived in Baghdad on November 23, 1990, and left for Jordan on the way back to the United States, with the 15-released hostages, on December 2, 1990.

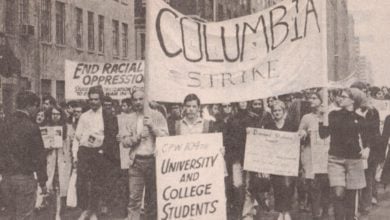

The delegation Ali led to Baghdad was organized by the U.S. anti-war movement that was at that time bringing thousands, and eventually hundreds of thousands, of people into the streets in an ever-growing mass street protest movement throughout the United States in 1990 and 1991.

I was one of the organizers for those protests. The Coalition to Stop U.S. Intervention in the Middle East (our admittedly unwieldy name) was made up of hundreds of grassroots peace and community organizations. Ramsey Clark had allowed his downtown Manhattan law office to be used rent-free as the headquarters and mobilization center of these anti-war organizers and volunteers who over-ran that small office from August 1990 during the entire carnage known as the first Gulf War that finally ended on February 28, 1991.

It was from these offices and under Ramsey Clark’s leadership that the Muhammad Ali peace delegation was conceived and initiated. Ramsey and Muhammad were good friends. That too was a story that contained an element of irony since Ramsey was the U.S. attorney general in 1967 when Ali was indicted on federal charges for his refusal to be drafted into the U.S. military. But later Ramsey worked in assisting on the successful Supreme Court legal appeal that overturned Ali’s conviction in 1971.

Ali’s delegation arrived in Baghdad and met with Saddam Hussein at about the same time George H.W. Bush arrived in Saudi Arabia to take Thanksgiving pictures and make patriotic speeches to the U.S. troops that were about to be sent into combat. In fact, that was why we went to Iraq at that particular moment: We were hoping to have contrasting images of Ali “talking” with Iraq while Bush was insisting on war with that country.

It took guts for Muhammad Ali to go to Iraq in 1990. He wanted to help prevent a war with Iraq but he was worried because we were going against the tide.

Our trip to Iraq was filled with unexpected surprises, some of which were truly bizarre. Much of what happened could not have been anticipated, at least by me.

When we first arrived in Baghdad on November 23, 1990, we were taken to Iraq’s most famous hotel, the Al-Rashid. It was early evening and we went straight to the dining area.

Al- Rashid’s 5-star dinner hall was packed with people feasting on the finest food. Most were not Arabs. They looked like they were from western countries. I remember remarking to someone at the buffet table that I didn’t expect so many western media people to be there, to which the person replied, “Most of these people are not media, they are hostages.”

What? We had been reading and watching lurid stories about the immense suffering of western hostages who Saddam Hussein wouldn’t let leave the country in an effort to hold off air strikes.

I couldn’t believe it. These were hostages? I went up to one table of 30-somethings who looked European. “Are you hostages?” They all laughed and told me they were indeed hostages. They were nurses from Ireland who were working in an Irish-run medical facility in Baghdad. They asked me if I wanted to join them for drinks at a bar following dinner.

It was surreal. We all went drinking and they told me their story. Iraq had confiscated their passports so they couldn’t leave the country, but they didn’t want to leave anyway. They were making very good salaries, better money than in Ireland and really enjoying themselves. I asked them if they were scared about being caught up in a war. They were completely dismissive. “There is no way there will be a war,” they told me. They were certain that all the war talk was just a prelude to a negotiated exit of Iraq from Kuwait and a resolution of outstanding issues between Iraq and Kuwait. I told them that the U.S. government doesn’t send hundreds of thousands of troops halfway around the world to negotiate. I think that our conversation was the very first that they held with someone who was convinced that war was really coming to Iraq.

Ali came to the bar too. He didn’t drink of course but he entertained the European hostages and the bar staff by doing magic tricks, including one that he had really mastered where he appeared to levitate at least two inches off the floor.

Magic tricks and jokes aside, Ali was deeply concerned.

As he told me numerous times during the trip, he was concerned not about what would happen to us in Iraq, but rather about retribution when we got home from the media and especially the U.S. government that had demonized him and sentenced him to prison for refusing to go to Vietnam.

He was especially concerned that unless he returned with American hostages that he would be figuratively crucified by the media for cavorting with the enemy at a time when the patriotic drums of war were being beaten at an increasingly feverish pitch. He was right to be worried.

Unlike the European “hostages” who were eating at 5-star hotels and going to bars, the American hostages were facing a much more unpleasant reality. The Iraqi government placed them in government houses and compounds located at strategic military sites. They were placed there as deterrents against the expected U.S. attack. Saddam thought that the United States would not be able to start bombing because these men, who were both workers and business subcontractors doing business in either Iraq or Kuwait, would be right in the line of fire.

While Saddam calculated, or miscalculated — as he regularly did when it came to military questions — that holding westerners in Iraq would serve as a deterrent to a U.S. bombing campaign, the truth is that the Washington “we-need-to-go-to-war again” lobby was thrilled that Saddam took hostages. It played fully into their demonization campaign and war preparations.

Anyone who opposed a war with Iraq was labeled as either an apologist for the hostage-taking Saddam or as a half-wit. Ali was treated as both by the government and the media.

Ali is cited now as a hero for having rescued the U.S. hostages but he and our delegation were treated with scorn and contempt at the time.

Huffington Post writer Andy Campbell succinctly captured the actual attitude towards our trip in his June 4, 2016, post-mortem piece “5 Stories You Didn’t Know About Muhammad Ali”:

“Ali was instantly criticized, taking flak from the likes of then-President George H.W. Bush and The New York Times, both of whom expressed concerns that he was fueling a propaganda machine. Speaking about Ali’s Parkinson’s disease, the Times wrote:

“‘Surely the strangest hostage-release campaign of recent days has been the ‘goodwill’ tour of Muhammad Ali, the former heavyweight boxing champion . . . he has attended meeting after meeting in Baghdad despite his frequent inability to speak clearly.’”

When we left from Iraq on December 2 with the American hostages, our delegation was greeted in Amman, Jordan, by State Department representatives. This was no happy greeting or celebration of freedom. Instead, the mood was grim. The U.S. government was infuriated that Ali had demonstrated that “talking” worked and moreso that it was the anti-war movement that had led the way in defiance of the government.

U.S. government representatives huddled with the hostages and tried to convince them that they leave Ali’s delegation and return on a plane provided by the State Department. One of the men told me they felt pressure from the U.S. government to abandon Ali even though they were immensely grateful for his effort.

In the end, I believe that six of the 15 stayed with us to JFK airport, where we had scheduled a press conference to speak about our trip. We insisted that Ali’s trip proved that “talks and negotiations” were clearly available as a means to prevent war. Of course, the George H.W. Bush administration wanted none of that. They did not want peace.

Muhammad Ali’s delegation to Iraq was considered a threat, and not an asset, by the Bush administration and the media, which was marching in lock-step with the Pentagon, just as it could be relied upon to do 12 years later in the lead up to the second Bush administration’s shock-and-awe invasion. The actual historical context is necessary to understand the “threat” posed by such a delegation in 1990.

Hundreds of thousands of U.S. troops, bombers and cruise missiles were being put into place in Saudi Arabia and the Persian Gulf for a war against Iraq. The atmosphere was very tense. We were not from the government but from the anti-war movement. By the time Ali met with Saddam on November 29, 1990 – in fact, on that very day – the U.S. government browbeat the UN Security Council into authorizing a war against Iraq. This was to be the first time in history that the United States was planning to launch a war and send U.S. troops into real military action in the Arab World. The stakes could not have been higher.

The biggest problem facing the U.S. war lobby (don’t forget Dick Cheney was then Secretary of Defense) was not Iraq’s military. Iraq was small and the Pentagon knew Iraq’s military weaknesses inside and out because it embedded U.S. officers and assets inside Iraqi units during the Iran-Iraq war that had only ended two years before.

The real problem facing policymakers was huge uncertainty about U.S. public opinion. The so-called “Vietnam Syndrome” was the consequence of the last major U.S. war that ended with its troops being driven from the battlefield in Southeast Asia while U.S. cities, high schools and college campuses became centers of intense social and political protest. This, not Iraq’s military, was what the Bush administration was worried about as it was readying the population for war.

To overcome the problem of still-deep anti-war feelings at home, the Bush government relied on a new tactic: a highly personalized demonization campaign in the mainstream media of the leader of the targeted country. Saddam Hussein was an easy target. “The greatest tyrant since Hitler” was the mantra. The media whipped up sensationalized anti-Saddam stories 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

This was the real context of Muhammad Ali’s trip to Iraq. It explains the animus he felt from the media and government. Ali went to meet directly with Saddam Hussein (aka the demon) in a trip that was not authorized by the U.S. government. It was organized by the very people who were organizing mass street protests at home aimed at arousing public opinion in a desperate bid to constrain the government from initiating the first-ever U.S. war in the Arab World – before it started.

Aside for the 15 very-grateful men who were released, Ali received practically no kudos or shout outs for saving the American hostages. This trip was considered subversive by policymakers who were wholly committed to the war drive and actually cared very little about the release of the hostages who had been caught in the middle.

A few weeks after we left Baghdad, Iraq agreed to allow all the other westerners to leave the country.

On January 16, 1991, the war that Muhammad Ali and millions of Americans wanted to stop began with a massive aerial destruction of the country. The U.S.-led air campaign dropped 88,500 tons of explosives on Iraq. Today, 26 years later, U.S. planes are still bombing Iraq. This is the fourth successive U.S. administration to drop bombs on Iraqi cities and towns.

The era of endless U.S. conflict in the Middle East, with all of its attendant human suffering in the Muslim world and beyond, began in 1991 despite Muhammad Ali’s courageous actions to do what he could to hold back the dogs of war. As the politicians eulogize Muhammad Ali, while artfully stripping his legacy of many of the courageous political positions that made him the target of the government when he was alive, we should remember what he really stood for.

Brian Becker is the National Coordinator of the anti-war ANSWER Coalition and the host of the daily news show “Loud & Clear” on Radio Sputnik.

[ALSO: Listen to a special one-hour show of Loud & Clear with Brian Becker about the legacy of Muhammad Ali. He is joined for the full hour by scholar and historian Dr. Anthony Monteiro, Askia Muhammad, Final Call journalist and news director of Pacifica Radio’s WPFW station in Washington, DC., and by activist and author Eugene Puryear.]