On July 30, more than two dozen activists from the Chicago area travelled by bus to the Logan Correctional Center to show support and solidarity for those inside the walls. Logan Correctional, located outside the small town of Lincoln is the state’s largest women’s prison. It recently gained notoriety when three inmates staged a hunger strike against the deplorable conditions inside that they have been forced to live in.

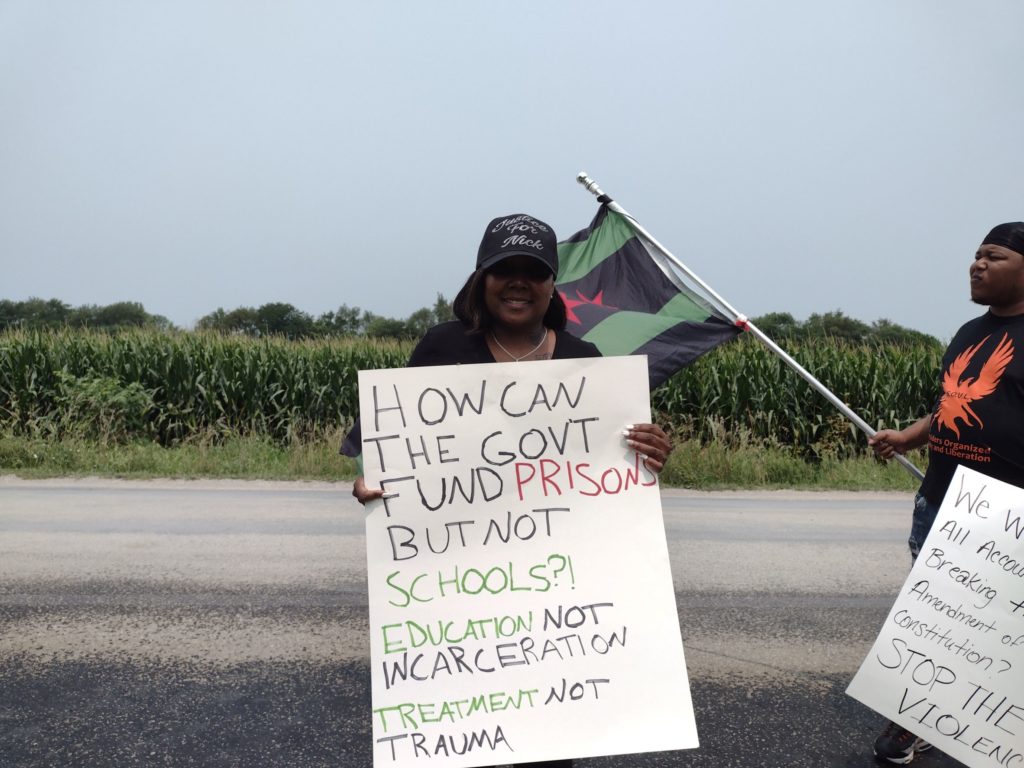

Demonstrators stood outside the yard’s barbed wire fencing with signs and bullhorns, chanting, speaking out and demanding an end to the racist system of mass incarceration. They demanded money for jobs, education, healthcare and mental health services rather than having that money be used to lock up and cage human beings.

At several points, those inside could be heard faintly through the walls shouting back, causing activists outside to pause and listen attentively to the responses of the women.

The demonstration was organized by Cassandra Greer-Lee, a Chicago activist who has been a staunch fighter for the rights of the incarcerated. “I knew someone that was incarcerated here,” she told Liberation News. “She would send me little tidbits about how horrible it was.” When she heard about the hunger strike, “That’s when a red flag said, okay, they need help.”

Greer-Lee immediately began the hard work of chartering a bus, organizing the trip, spreading the word and preparing to make the three-hour trip from Chicago to Logan Correctional Center.

Sloshing through sewage

On May 29, pipes burst in one of the housing units in the aging facility causing a backup of sewage that flowed up through drains and sinks. Women inside reported walking through water a foot deep for several days, working furiously to sweep out noxious water from their cells that kept coming up before authorities took any action. Their belongings were destroyed and the women found themselves trapped in highly unsanitary conditions.

Eventually, 49 women were moved to temporary units while prison officials claimed they would make needed repairs. However, these temporary units were filthy and inmates were forced to share even closer quarters than usual with no way to physically distance from one another. Perhaps even worse, these units had no phones or no internet, depriving the women of any contact with their families and the outside world.

On June 4, inmates wrote a letter to Logan officials asking that they be moved to clean and functional housing. After getting no satisfaction for their demands, three of the inmates then began a hunger strike on June 7. After three days prison officials promised to make the needed repairs and return the inmates to their previous units and the hunger strike ended.

However, women inside reported that they themselves were forced to clean their own units with substandard supplies. Even after this, the units still reeked of sewage and several of the toilets no longer worked. Prison officials even denied inmates requests for hepatitis shots after inmates feared what they may have contracted in the sewage.

The mass incarceration of women

This incident is only the latest in a long string of problems that have plagued the Logan Correctional Center in particular.

The prison sits on a 150-acre plot in a rural Illinois county roughly 30 miles north from Springfield. The main entrance is found at the end of a long gravel road abutted by corn fields, which by late July, hang limply above your head drooping in the heat. Swarms of hoverflies move across the road, and as the sun bears down, one can’t help but be reminded that there is no air conditioning for those inside the prison.

Logan opened as a prison in 1978 — although the buildings were constructed decades earlier in 1929 — during a period when the U.S. prison population began ballooning in size. Initially used as a men’s facility, it was converted into a women’s facility in 2013 by combining the populations of two other women’s prisons in a move that has been described by the John Howard Association of Illinois as “under resourced and ill-conceived.” At that time more than 2,000 women were crammed into a facility which had previously housed 1,500 men.

This shift followed nationwide and statewide trends. Women are the fastest growing prison population. Between 1980 and 2014 the rate of growth for women being imprisoned outpaced that of men by 50%. Between those same years, the number of women behind bars in Illinois skyrocketed 767%.

Today, the Logan facility houses just over 1,000 women, almost all of whom are isolated, far from their families and loved ones. Surveys have found that upwards of 90% of them have experienced sexual or physical abuse in the past. More than two thirds of them are mothers.

A 2016 study funded by the U.S. Department of Justice that looked at Logan Correctional specifically found overcrowded conditions, abuse against mentally ill inmates, excessive force and the overuse of harsh punishments, including isolation and segregation. Women reported being strip-searched behind cardboard boxes and frequent verbal abuse from guards and staff.

The racist character of mass incarceration also expressed itself in the prison’s policies. Black women were not allowed to wear braids or dreadlocks during family visits on the excuse that such hairstyles could be used to hide ‘contraband.’ Black women are 42% of the Illinois women’s prison population, while representing only 15% of the state’s population.

More than half of the women at the prison are also classified as “severely mentally ill,” yet mental health resources are scant to nonexistent, with staff lacking any kind of training or sensitivity toward those incarcerated. In fact, in interviews staff were reported referring to inmates as “animals” and calling them “worthless” and “crazy.”

The toll of COVID-19

Greer-Lee knows all too well the reality of mistreatment that happens behind bars. On April 12, 2020, her husband Nickolas Lee died of COVID-19 that he contracted while in Cook County Jail. Like most people in the jail, Lee had not been convicted of a crime, but he received a death sentence nonetheless.

Prisons throughout the country have been hotspots for COVID-19, exacerbated by tight living quarters and lack of access to PPE or even basic cleaning supplies. Early in the pandemic, the Cook County Jail in particular emerged as one of the national epicenters of the virus with more than 300 inmates testing positive at its peak. To date, at least 10 people in the jail have died as a result of the disease.

Logan Correctional Center has also experienced its own COVID-19 spike with 77 cases confirmed in August 2020. Despite this, a survey of inmates conducted in April last year found that almost a third of inmates did not have enough soap to regularly wash their hands, and that almost none of them received additional cleaning supplies.

In Chicago, while her husband’s health faded, Greer-Lee made 132 calls to officials at the jail, begging anyone she could talk to to do something for her husband. Ultimately she was ignored until it was too late.

Since then, Greer-Lee has staged weekly and sometimes daily protests outside of the Cook County Jail — some larger, some smaller. Through rain or shine, bitter cold or suffocating heat, she is out there making sure that those inside are not forgotten.

She described the trip to Logan Correctional Center as an extension of that solidarity: “Since my husband was murdered in Cook County Jail, I see that results come when you are present. They see a spotlight has been shone on them and they know, ‘oh they have outside help.’ We were powerful because we came and we stood and we talked about the injustice, and we let the ladies know that we hear their cries.”

Black August and Black liberation

The protest was especially poignant for some given the approach of Black August, which commemorates the sacrifices of fighters in the Black liberation struggle and the call to release all political prisoners. One of those who travelled from Chicago downstate to the prison was Fred Hampton, Jr. the son of assassinated Black Panther Party Illinois leader Fred Hampton.

Today Hampton, Jr. works with the Black Panther Party Cubs and the Prisoners of Conscience Committee. He talks about the necessity of prison solidarity by quoting Huey P. Newton: “The prison is a microcosm of the outside community… a main staple of our work deals with the issues inside the prisons, these modern day concentration camps. I’m duty bound and obligated to help bring light to the conditions happening inside these camps.”

Hampton, Jr. also knows firsthand the reality of prisons. Like his father before him, he was also a political prisoner for a time, and this informs his activism today.

“I don’t take it lightly. I was fortunate to come out with my life intact and my sanity intact,” he explained to Liberation News. “Though the propaganda put out by the system is that [prison] is designed to rehabilitate you, the reality is it is designed to break the spirit of men, women and children alike.”

Like many outside the prison, he connected this action with the long history of fighting for Black liberation and against the racist system of mass incarceration. “We keep the cases in mind of Mumia Abu-Jamal, Sundiata Acoli, Ruchell ‘Cinque’ Magee, and countless others who have been caught in these concentration camps throughout the country and throughout the world.”

The struggle will continue

After making some hours of speeches, chants and solidarity, demonstrators made their way back to the bus to begin the drive back to Chicago. Greer-Lee reflected on the trip on the bus ride back: “For me it’s always bittersweet. It’s only one little part that’s sweet, and that is that I hope and pray — and by the sounds that I heard from some of them — I know that they knew we were there. So I hope that that little bit of our presence gives them hope to keep fighting and to keep their head up and know that somebody cares and somebody heard their cries. The bitter part is that I have to leave them back there.”

She plans to continue organizing activists to travel to prisons around the state and region in order to show that it is not just one particular prison, but the entire system of mass incarceration that oppresses and dehumanizes working-class people.

“I’m inspired,” said Hampton, Jr. “Sister Cassandra has took her pain in regard to the murder of her husband Nickolas Lee and let it be a point of unity for organizing with others under capitalism. In fact, it was therapeutic to be out here. To see the gun towers, guards, flashbangs, the different tactics and conditions that I was subjected to from the other side. It’s something that we have to continually put out there.”

Feature photo: Activists rally outside the Logan Correctional Center women’s prison near Lincoln, Illinois. Liberation photo