No Harveys here: Sexual harassment is a working class issue is a three-part series on workers fighting sexual harassment in the hotels, homes and the growing fields.

No Harveys here: Sexual harassment is a working class issue is a three-part series on workers fighting sexual harassment in the hotels, homes and the growing fields.

The Beverly Peninsula Hotel, a hotel for the rich, was Harvey Weinstein’s home away from home. It was also the place where he preyed on women in the privacy of his suite. If well-known actresses found themselves fending off unwanted sex there, consider the vulnerability of an immigrant housekeeper, cleaning the room alone, for a tiny salary .

Sexual assault is a crime that abuses power. Its victims are those who are more vulnerable than the perpetrator. Women, gender non-conforming people and men can be targeted. For many working class women, sexual harassment or its threat are everyday occurrences.

Housekeepers, janitors on a night shift and agricultural workers in the fields, are particularly vulnerable because they are often alone, according to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Many of these workers are immigrants, undocumented or the sole support of extended families.

Some trade unions are fighting to keep these workers safe. Housekeepers in New York City, Chicago and Seattle have won the right to have “panic buttons” which they press if threatened or assaulted sexually, so that help will arrive and the perpetrator held accountable. A campaign is underway to bring this protection to housekeepers in Miami-Dade county, Florida.

30,000 NYC housekeepers win panic buttons

In 2012, the New York Hotel Trades Council won a contract for 30,000 workers that guaranteed the use of panic buttons for housekeepers covered under the agreement. The year before, French politician Dominique Strauss-Kahn was accused of assaulting a housekeeper at a New York hotel, bring the issue to public attention.

Unite Here, a trade union representing housekeepers and other service workers in the U.S. and Canada, has gotten legislation passed mandating the “panic buttons” in Seattle and Chicago. A similar effort is underway in Miami. A panic button law did not pass in Long Beach, Ca., where the Beverly Hills Peninsula is located, in the face of strong opposition by the hotel industry.

‘Don’t let a guest between you and the door’

They are much in need. Employees at Beverly Hills Peninsula here say guests treat them like property. They report being groped, grabbed from behind, guests appearing naked, masturbating in front of them, trying to touch or trap them in hallways, rubbing their genitals against them. Workers advise each other to “never let a guest get between you and a door,” and to “always keep a piece of furniture between you and a guest.” (New York Times) The workers do not have a union. Many avoid reporting harassment for fear of being fired.

58 percent of Chicago Hotel workers sexually harassed

Last year, Unite Here surveyed 500 of its Chicago area members who work in hotels and casinos as housekeepers and servers, many of them Latino and Asian immigrants. They found that 58 percent of hotel workers and 77 percent of casino workers had been sexually harassed by a guest; 49 percent of hotel workers had experienced a guest answering the door naked or otherwise exposing himself; 56 percent of hotel workers who had reported

harassment said they didn’t feel safe on the job afterward; 65 percent of casino cocktail servers said a guest had touched or tried to touch them without permission; almost 40 percent of casino workers said they’d been

pressured for a date or a sexual favor.

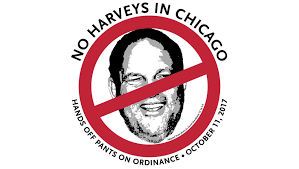

‘No Harveys in Chicago’

On Oct. 11, 2017, the Chicago City Council passed a “Hands Off, Pants On” ordinance. Chicago housekeepers celebrated, wearing “No Harveys in Chicago” T-shirts . By July 1, 2018, hotels there must provide housekeepers and others who work alone in guest rooms or bathrooms with panic buttons. Hotels are also obliged to develop sexual harassment policies that show workers how to report incidents, and give workers time to file police complaints. This ordinance is in effect whether the workers are unionized or not. A similar ordinance was passed in in Seattle.

Wendi Walsh, secretary-treasurer of Unite Here Local 355 said the ordinance could alter what she calls a pervasive hotel practice of keeping incidents of sexual harassment quiet, with hotels often trying to solve them internally instead of seeking police involvement. The Seattle ordinance, for instance, requires that hotels keep a record of guests accused of sexual harassment.

“A lot of time these [acts are committed by] regular guests or VIPs. The same guest comes back the next day or month or year,” Walsh said. “So it tells the housekeeper that their experience is less important than the guest.”

Hotels pander to wealthy guests

This is very much the case at the Beverly Hills Peninsula. Hotels continue to indulge the big spenders who misbehave and court their return. For example, Weinstein, who would book a suite for himself and rooms for a team of staff, brought hundreds of thousands of dollars to the Penninsula for each stay. These clients are catered to by the hotel in every way. Workers say the hotels put discretion and deference to powerful customers before the well-being and safety of the housekeepers and janitors who work there.

Unite Here waged a year-long struggle to get the Long Beach City Council to pass an ordinance extending protection against sexual harassment and abuse to all of the city’s hotel workers, not only those covered by a union contract. The ordinance was narrowly defeated in a 5-4 vote . The Long Beach Chamber of Commerce campaigned against the regulation, claiming the ordinance would cost hotels $3 million.

Miami workers who report abuse put on the defensive

Miami-Dade’s estimated 11,500 housekeepers and other hotel workers are also fighting for a “Hands off Pants on” ordinance. The Miami Beach proposal is modeled after the mandatory practices in Chicago and Seattle, that arm staff with panic buttons in case there is an incident. (Miami Herald)

The portable panic buttons would connect to hotel security or management, allowing them to act quickly if a worker is harassed or assaulted. The proposed law would also create a framework for reporting incidents, including allowing workers to contact police, an anti-retaliation policy prohibiting hotels from firing workers who speak out and a mechanism for monitoring guests who act improperly toward staff.

Currently, housekeepers who report sexual abuse have been put on the defensive by management. For example, when Fontainebleau hotel housekeeper Gerdine Verssagne reported to management that a naked male guest entered a room she was cleaning, the hotel not only doubted her story, but checked to see whether she was supposed to be working at that time. Fontainebleau hotel housekeepers can spend up to four hours getting to work on county buses, as high rents in the county have pushed workers farther away from their jobs.

Before drafting the ordinance, Unite Here Local 355, which represents 200 housekeepers at the Fontainebleau Hotel, plans to follow the Chicago example and conduct a survey on sexual harassment before submitting the ordinance.

Nationally, the American Hotel and Lodging Association has opposed panic button measures, and has developed a social media campaign to try to stop them. The association calls hotel safety ordinances a “fig leaf” for other union demands, like higher minimum wages and caps on workloads. It does not explain, however, what is wrong with higher minimum wages and caps on workloads, or why it would deny such basic rights to its workers.