Walk into any book store, and you are sure to find at least one children’s book about Helen Keller — but you will have trouble finding any that mention she was a socialist. You would be lucky to find one that calls her an activist, or talks about her adult life at all. Even some books for adults only talk about Keller as a disability rights activist, stripping her lifelong work of its true revolutionary politics.

July 26 is the anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act which passed in 1990, the same year of the first Disability Pride Parade in Boston. Although Keller died more than three decades before the ADA, her name is often invoked around this anniversary because her generation laid the groundwork for the political organizers of the 1970-90s who fought for and won the act.

Early life

Keller became deaf and blind from a severe fever she had as an infant. She first learned to communicate with words at the age of seven from the instruction from Anne Sullivan, a graduate from the Perkins School for the Blind.

Keller was catapulted into fame before the age of 11 when the principal at the Perkins School embellished reports from Sullivan, and released them to the press.

At a time when it was still rare for any woman to attend college, Keller was the first deafblind student to graduate college in the United States. She later said about her college experience,

“College isn’t the place to go for any ideas. I thought I was going to college to be educated…. They did not teach me about things as they are today, or about the vital problems of the people. They taught me Greek drama and Roman history, the celebrated achievements of war rather than those of the heroes of peace…. Education taught me that it was a finer thing to be a Napoleon than to create a new potato.”

Becoming a socialist

She became a member of the Socialist Party in 1909, and joined the Industrial Workers of the World in 1912.

“How did I become a Socialist? By reading,” Keller writes in one of her first articles for The New York Call. She first read H.G. Wells’ Old Worlds for New, Progress and Poverty by Henry George, Karl Marx, and periodicals from socialist parties abroad. She read braille in English, French, German, Greek and Latin, and friends would come read to her by signing the manual alphabet in the palm of her hand.

She often cited the 1912 Textile Workers “Bread and Roses” Strike in Lawrence, Massachusetts as another inspiration for becoming a socialist. Later in life she caused a press scandal when she wrote to strike leader Elizabeth Gurley Flynn in prison, and the letter was intercepted and published.

Keller was involved in many struggles, including women’s suffrage, abortion, labor unions, disability rights, civil rights, and fighting against the imperialist war machine. She was a founder of the American Civil Liberties Union.

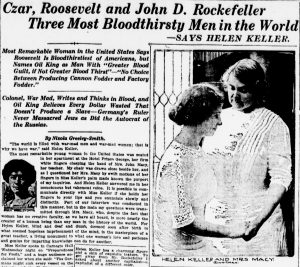

Press turns against Keller

The more she wrote and published her socialist ideas, the more the press turned against Keller. But by then, she was too famous to just ignore.

The “angelic” child the papers adored was now smeared. One day she was a child genius and a miracle — the next, she was being taken advantage of due to the “manifest limitations of her development,” and her views could not be trusted to truly be her own.

In 1924 she wrote in a letter, “So long as I confine my activities to social service and the blind, they compliment me extravagantly, calling me ‘arch priestess of the sightless,’ ‘wonder woman,’ and a ‘modern miracle.’ But when it comes to a discussion of poverty, and I maintain that it is the result of wrong economics — that the industrial system under which we live is at the root of much of the physical deafness and blindness in the world — that is a different matter!”

What she fought for

Keller believed that the U.S. government should not enter World War I, a position that was controversial even on the left.

In her speech Menace of the Militarist Program, she said:

“In spite of the historical proof of the futility of war, the United States is preparing to raise a billion dollars and a million soldiers in preparation for war. Behind the active agitators for defense you will find J.P. Morgan & Co., and the capitalists who have invested their money in shrapnel plants, and others that turn out implements of murder. They want armaments because they beget war, for these capitalists want to develop new markets for their hideous traffic…. Nothing is to be gained by the workers from war. They suffer all the miseries, while the rulers reap the rewards. Their wages are not increased, nor their toil made lighter, nor their homes made more comfortable. The army they are supposed to raise can be used to break strikes as well as defend the people.”

Keller was an anti-racist and a supporter of the NAACP. A 1916 letter she wrote that expressed solidarity with the struggles of Black workers in the South was released to the press and caused outrage. “Ashamed in my very soul I behold in my own beloved southland the tears of those who are oppressed, those who must bring up their sons and daughters in bondage to be servants, because others have their fields and vineyards, and on the side of the oppressor is power.”

She fought for militant women’s suffrage and abortion rights. In an article Why Men Need Women Suffrage, she wrote: “Men spent hundreds of years and did much hard fighting to get the rights they now call divine, immutable and inalienable. Today women are demanding rights that tomorrow nobody will be foolhardy enough to question.”

Keller caused yet another press scandal when she published an article about venereal diseases, like syphilis, that were a leading cause of blindness in women. It was scandalous because no one talked about venereal diseases at all, and she discussed them as a class and women’s health issue.

She understood that charity alone was not enough to liberate anyone. Disabled people lived in poverty because they were not allowed to work for wages, and poverty and wage labor in turn could create disability. Class and disability were fundamentally connected, she proclaimed.

Keller defended the Soviet Union’s socialist project. She traveled the world visiting disabled soldiers. She was particularly adored in Japan, where she was greeted in 1948 by thousands of people, many made deaf and blind by the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

The FBI had a file on Keller, but she was spared from the McCarthy hearings because of her fame and her infantilization by the press, publishing houses and Hollywood. However, many of her friends and comrades were tried and imprisoned.

Later life and career

When the first of many movies about her life debuted in 1919, the Actors Equity union was on strike. Instead of attending the opening, she joined the picket line.

In 1924, she accepted a position as a fundraiser and ambassador for the new American Foundation for the Blind, an organization that helped secure some of the first disability rights legislation in the United States. Keller’s radical socialist politics ruffled feathers at AFB, but they needed her fame to fundraise. In her time there, she pushed the organization to also fight for the rights of Black disabled people, and they finally made a service for deafblind people after 23 years of her advocacy.

Helen Keller died in 1968 at the age of 87.

Importance today

We remember Helen Keller for the extraordinary person she was: a writer, public speaker, and revolutionary socialist for a majority of her life — the part of her life that is the least often talked about.

The truth Keller exposed over a century ago is still true today. Disabled people are often trapped in poverty because of capitalism, and the poverty of capitalism itself can also create disability. Disabled people disproportionately face poverty, homelessness, police brutality and incarceration.

Hellen Keller’s fight for a socialist society free of the drive for profits is possible. We have the ability to meet every person’s needs, to guarantee that every disabled person has the right to affordable housing, healthcare, and education.

In her speech New Vision for the Blind, Keller said,

“This is not a time of gentleness, of timid beginnings that steal into life with soft apologies and dainty grace. It is a time for loud voiced, open speech and fearless thinking; a time of striving and conscious manhood, a time of all that is robust and vehement and bold; a time radiant with new ideals, new hopes of true democracy. I love it, for it thrills me and gives me a feeling that I shall face great and terrible things. I am a child of my generation, and I rejoice that I live in such a splendidly disturbing time.”