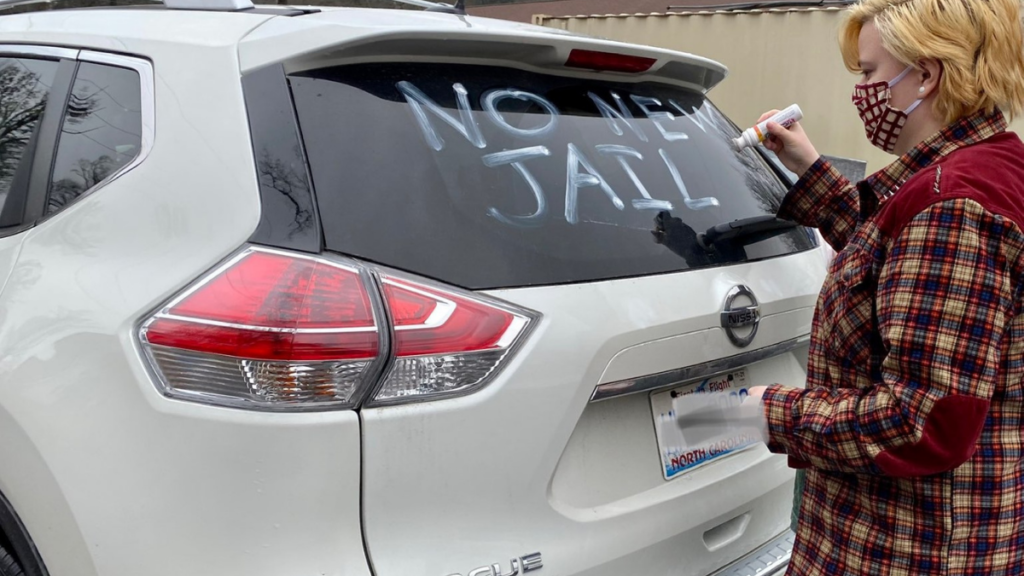

In North Carolina’s Haywood County a car protest was organized on Feb. 1 by the Party for Socialism and Liberation to oppose Haywood County’s plan to expand the existing jail in Waynesville, North Carolina. The caravan was also attended by Down Home North Carolina, an organization which began the No New Jail campaign in 2020 to stop Haywood County from spending $16.5 million to construct a new detention facility.

Cars that joined the caravan had signs that read: “If they build it, they will fill it,” “No new jail in Haywood County,” “Fund services, not jails” and “Treatment, not jails.” As the caravan went through the busy streets of Waynesville, many passersby showed their support to the drivers.

Speaking to the attendees, PSL organizer Faye Gant said, “If they are to expand the jail, then they have the incentive to fill it [with more people].”

Organizers and community members demanded the money allocated for the jail expansion be spent on services that prevent people from being detained in the first place.

Jesse-Lee Dunlap, organizer with Down Home, said to Liberation News, “The cost of the jail is $16 million. And all the things that we want to do, to prevent people from going to the jail in the first place would only cost less than $4 million a year. We could have 40 years’ worth of programs to help people in our community using the cost of this jail expansion.”

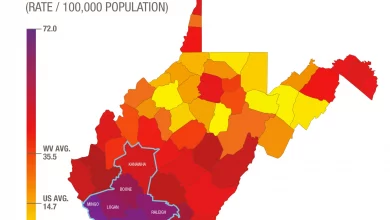

In Haywood County, only 37% of those incarcerated face felony charges, meaning that 63% of the inmates are only charged with misdemeanors. Meanwhile, a Western Carolina University study shows that 85% of the people in Haywood County jail showed signs consistent with substance abuse disorder, more than 50% of inmates have symptoms of PTSD, and a third suffered from symptoms of depression.

Activists emphasized the need for funding allocation towards licensed clinical social workers and therapists in all schools, expanding Medicaid and mental health care services and treatment centers for those suffering from substance abuse. Protesters identified lack of affordable housing in the county as a major contributing factor to the cycle of recidivism. Seventy percent of the people released from Haywood County’s detention center do not have a home to go to upon release, making them vulnerable to landing back in jail soon.

Chris Hoag, a Criminal Justice major at Western Carolina University who had visited the jail, spoke about the conditions within. He said, “Conditions are inhumane. In this jail, there is a single window where prisoners are held. It is 30 feet up and it is only as big as a car window. That is their singular source of daylight. They have no yard. They can never go outside. Their exercise is walking in circles around the prison block.”

He added, “There is an opioid crisis. We need rehabilitation centers. Addicts deserve help instead of being put in jail. When they get out, they [abuse substances] again because they can’t get help.”

A study of more than 200,000 people released from North Carolina’s prison system between the years 2000 and 2015 found formerly incarcerated people were 40 times more likely to die from an opioid overdose during the first two weeks after their release, and 11 times more likely to die of an overdose over the course of the first year after release compared to the general public.

The caravan protest made its demands clear to Haywood County officials; money for childcare, jobs, food, housing, and healthcare; not more jails and prisons.