The heroic 11-day truck drivers strike in Brazil was a powerful show of force in response to the pro-market policies of the coup government of Michel Temer, whose burden has been put squarely on the shoulders of the working class.

The National Federation of Autonomous Truckers reported 451 road blocks by the fourth day of the strike. Airports across the country cancelled more than 270 flights during the first week of the strike due to fuel shortages, with nine airports having no fuel reserves as of the ninth day. The six largest retail markets in Brazil, which account for nearly half of national retail sales, took a loss of approximately $840 million over the first eight days of the strike.

The core demand revolved around the cost of diesel fuel. Truckers demanded an end to daily adjustments to fuel prices by the state-controlled oil company Petrobras, as well as the elimination of certain fuel taxes. Additionally, drivers demanded toll exemptions for empty trucks and a minimum price for freight. These and other economic demands were supplemented with calls for the resignation of Pedro Parente, the head of Petrobras, with many truckers also demanding that Temer step down.

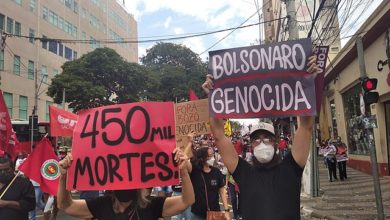

The truckers were not alone. Oil workers declared their own strike in solidarity, despite Brazil’s Superior Tribunal on Labor declaring their call for a work stoppage “abusive” and threatening massive fines. Demonstrations in support of truck drivers took place in several states. A poll by Datafolha found 87 percent support for the strike — a sign of widespread opposition to the high fuel prices and, more broadly, to the dire economic situation that has engulfed the country.

Whose oil?

Under the slogan “The oil is ours,” Petrobras was founded in 1953 as a state-owned company, part of a project to modernize Brazilian capitalism through heavy government intervention in the economy and protection of strategic resources such as energy. A significant sector of the Brazilian capitalist class, in no small part due to their own connections with foreign interests, opposed the creation of Petrobras and other nationalist projects. In spite of their opposition, the Brazilian state maintained a monopoly on oil extraction and refinery operations in Brazil for over 40 years, which provided protection from global economic turmoil and the whims of the market.

The struggle over Brazil’s energy resources continues today. On one side are those who defend a nationalist policy — these are heterogeneous class forces with different interests, ranging from workers who benefit from subsidies to sectors of domestic industry sensitive to oil prices. On the other side are multinational oil companies, market speculators and sectors of the Brazilian capitalist class allied with foreign capital who seek to enrich themselves from Brazil’s energy resources.

In 1997, under the neoliberal government of Fernando Henrique Cardoso, the Petrobras monopoly over Brazilian oil was ended. Foreign oil corporations made their way into Brazil. Soon after, Petrobras began trading on the New York Stock Exchange. State control was maintained, but the infusion of foreign capital made it subject to the demands of international investors who couldn’t care less about national development or fuel subsidies for the poor.

Brazil’s oil and Petrobras were among the most coveted prizes of the 2016 coup. Rich reserves discovered in the mid-2000s deep in the pre-salt layer off the coast of Brazil had been off limits to foreign corporations under the governments of Rousseff and her predecessor Luís Inácio Lula da Silva. Temer’s government quickly put an end to those protections. Exxon, Chevron and Shell all snagged exploration rights in auctions held earlier this year. The full privatization of Petrobras with no restrictions on the demands of capital is the ultimate goal.

The present battle over fuel prices is only another expression of these conflicting interests. Cooking gas, diesel and gasoline are essential for the livelihood of millions of workers. Price subsidies ensure that these items remain accessible to the population, but would impose limits on the profits of investors. By tying fuel prices to the exchange rate of the dollar and oil prices in the global market, the Temer government has made it clear whose side they’re on.

strong>The role of the military< A sector of the Brazilian right has become more vocal in recent years calling for military intervention as the solution to the political crisis. These elements look back fondly on the repressive dictatorship that ruled the country for two decades -- a period when military decrees became the law of the land, political parties were abolished, workers and left organizations were extinguished and political dissidents were forced into exiled, disappeared, imprisoned, tortured or killed. The truckers' strike provided an opportunity for right-wing agitators to infiltrate the movement with the banner of military intervention. This banner has no organic roots in the Brazilian working class movement whatsoever. Labor unions, left parties and mass organizations condemn the 1964 coup as one of the darkest moments in Brazilian history and wholeheartedly oppose any new intervention by the armed forces. The adoption of pro-intervention slogans of the right-wing by some strikers, even if only by a minority, is a dangerous development for a country that endured a military dictatorship for 21 years. Unions and left organizations have issued numerous statements in recent days to counter the pro-intervention trend among workers, detailing the history of military repression in Brazil and attempting to dispel any false hopes that the military might bring salvation to the Brazilian working class. The motives and hopes of these workers are, of course, entirely different from the fascists at the head of the pro-intervention movement. Many workers are growing doubtful that an institutional solution to the political crisis can be found. Former president Lula, forecast to win the upcoming October presidential elections with overwhelming support, was illegally jailed on April 7 following a sham political trial and is likely to be barred from running. Political disenfranchisement, untenable economic conditions and uncertainty over whether the elections will give expression to the aspirations of workers has led some to turn to the military to intervene on their behalf.

The military has indeed intervened but, as expected, not on behalf of workers. Under Temer’s orders, the armed forces helped unblock roads firing rubber bullets and gas at strikers, and occupied the Port of Santos to guarantee the movement of cargo. The military deployment was a key factor in ending the strike.

What can solve the crisis in Brazil?

This outburst of grievances, a reflection of the political crisis that continues unabated in Brazil, could not be easily contained. Temer’s carrot-and-stick approach combined a military intervention to unblock roads along with a meager price reduction of a few cents on the gallon of diesel and a freeze on fuel price adjustments for a mere 60 days. Adding insult to injury, the government dropped nearly approximately $53 million in funding for social programs to subsidize the price reduction. Letting oil investors bear the burden was not even considered.

Such steps might have been sufficient to cripple the strike during ordinary times, but had limited impact in the present political climate. The concessions were met with contempt from the rank-and-file. Even as national and local unions leaders looked to bring the strike to a close under tremendous pressure and threats from the government, truckers remained mobilized and enforcing roadblocks throughout the country. Drivers used WhatsApp and other social networks extensively to share videos with demands, inform others of actions and road closures, and encourage each other to remain united and strong.

At first glance, the immediate gains of the strike were limited. The small reduction in the price of diesel and 60-day price freeze will provide temporary and limited relief. Parente has resigned as head of Petrobras, but his replacement by the market-friendly chief financial officer of Petrobras, Ivan Monteiro, indicates no fundamental change of course by the government.

However, the strike has unambiguously asserted the weight of labor and its potential to be a decisive factor in determining the direction of the country. The capitalists know and fear the power of labor. That is the very reason that Petrobras stock tumbled, and that the army, navy and air force were all mobilized against the strikers.

The fundamental issues remain unresolved — not just for truckers but for all of Brazil’s working class. Official unemployment is at 12.9 percent, and real unemployment is much higher. Underemployment is widespread. Public workers across the country have been fighting for back pay, sometimes adding up to several months of salary, with labor actions and strikes happening in several states. This dire situation makes the entire country a hot bed for mass organizing and labor actions that could break out at any moment.

With the sharpening of the economic and political crisis, major struggles are certain to flare up anew.