In May 2021, Albuquerque city officials and business leaders endorsed a project to publicly finance and build a soccer stadium in the city’s downtown area for a privately-owned soccer franchise. This project is the dream of wealthy New Mexico United soccer team CEO Peter Trevisani and was quickly endorsed by Mayor Tim Keller (D). Early negative reaction from the public was ignored, and the city council quickly voted to add a $50 million stadium bond measure to this November’s ballot.

Local elites overseeing pro-corporate development projects expected an easy win. They did not expect the residents to be able to mount an effective resistance. They were wrong.

Community members launched a grassroots campaign called Stop the Stadium to fight against gentrification and displacement of Albuquerque’s historic working-class neighborhoods by the stadium. Instead of using public money for the development of a luxury sports arena, Stop the Stadium demands that all available resources be used to address the severe housing crisis in Albuquerque, including housing the homeless.

A massive door-knocking operation by Albuquerque residents began on Sept. 18. Stop the Stadium volunteers focused on the historic downtown neighborhoods of Barelas, South Broadway, San Jose, Santa Barbara-Martineztown and Wells Park, all near the proposed stadium sites. Residents in these neighborhoods had not been consulted and were outraged by the gentrification project.

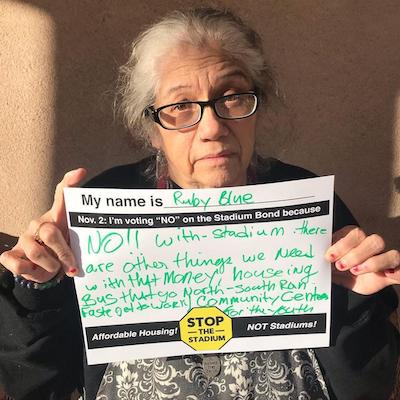

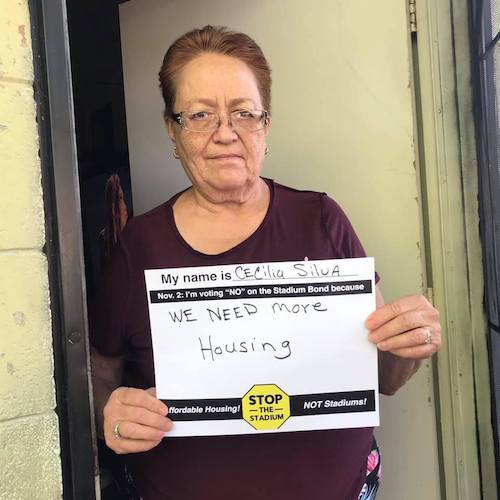

Stop the Stadium volunteers found overwhelming opposition to the stadium inside Albuquerque’s historic communities.

Lori lives in the impoverished and neglected South Valley community. She told Stop the Stadium, “The city needs to fix the roads.” Pointing at the crumbling pavement in front of her home, she said, “I have lived here for thirty years. I have cracks in the foundations of my house now and a pretty bad leak.” Repairing the infrastructure in neighborhoods similar to Lori’s all over Albuquerque has long been ignored by city officials.

Shannon is a longtime resident on the other side of one of the proposed project stadium sites. She didn’t even realize there was going to be a vote on the project. She told Stop the Stadium that her landlord had recently raised the rent on the property where she has lived for thirty years. She now worries that a stadium will make rent go up even more and she will have to find another place to live with her kids.

When volunteers went into neighborhoods farther away from the proposed stadium sites, they met residents who had already been displaced from downtown neighborhoods by other corporate “revitalization” projects.

A theme that Stop the Stadium volunteers found over and over again when talking with the community was that residents have priorities other than a stadium to use precious taxpayer money on.

One high school student told volunteers that her school was not able to keep enough soap and paper towels in the bathrooms. More than 25 percent of New Mexico’s students live in official poverty. Lilia, an Albuquerque educator said, “My students need housing before a stadium!”

The biggest rallying cry of all has been around the issue of housing, not only preventing the displacement of longtime residents in frontline neighborhoods but utilizing all available resources to address the severe housing crisis. In Albuquerque, rent has gone up on average 17 percent this year. Construction of new housing units is increasing, while the number of “affordable” housing units is decreasing. The city is short 15,000 affordable rental units right now.

Sofia, a Barelas resident, told Stop the Stadium, “My mom moved to Barelas 27 years ago and has lived here ever since. She was secretary of the Barelas Community Coalition board for over 10 years. I was born and raised here. I studied sociology in college in Los Angeles, and did my main research on gentrification happening there. Now I see the same patterns happening in my community here.”

Stop the Stadium volunteers have spoken face-to-face with thousands of anti-stadium residents, listening to their concerns and organizing rank-and-file neighborhood opposition. Meanwhile, local politicians and the multi-millionaire team owners they serve have spent $1 million on TV commercials and glossy mailers to trick the public. In desperation, they dropped $115k last week alone.

As the Nov. 2 vote approaches, the struggle between mega-rich franchise owners on one side and working-class residents on the other is heating up.

Stop the Stadium has a mass march planned for Nov. 1 at 5:00pm in Triangle Park.

Lead graphic: Screenshot of CAA ICON Architects feasibility of multi-use stadium.