Originally posted Sept. 30 on the online magazine of environmental politics in New Mexico, La Jicarita.

Members of Steelworkers Local 9424-3 in Bayard, NM are employed at one of the world’s largest open-pit copper mines owned by one of the world’s most profitable companies, Freeport-McMoRan. They voted last week 236 to 83 in favor of decertifying the union.

The vote was the culmination of six months of union busting work by Freeport employee Irvin Shane Shores, a Deming-resident and recent Freeport-McMoRan employee. According to the National Labor Relations Board, any employee who no longer wants a union to represent him or her is entitled to seek an election to determine if a majority of their coworkers agree.

In mid-August Shores circulated a petition asking members of the Steelworkers to decertify the union. He collected signatures from more than 30 percent of members of the bargaining unit, thus triggering the decertification vote. The National Labor Relations Board scheduled the election for September 17 and 18.

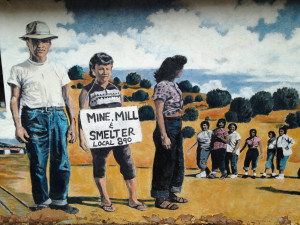

The local Steelworkers union Shores decertified is the inheritor of Mine-Mill Local 890, a union made famous by the 1954 film “Salt of the Earth”, which dramatized Local 890’s 1951 Empire Zinc strike. A number of members of the creative team behind the film had been blacklisted by Hollywood. The director, Herbert Biberman, went to jail for refusing to cooperate with the House Un-American Activities Committee, which investigated communist “infiltration” in politics, entertainment and education, among other industries.

The film was financed by the national office of Local 890, the International Mine, Mill & Smelter Workers Union, which was expelled from the Congress of Industrial Organizations in 1950 for presumed communist influence.

The aggressive, pro-labor message made the film an instant favorite among leftists and labor unions. It found an enthusiastic audience in union hall screenings all over the US. It was banned or boycotted everywhere else. The film and its creators were condemned by the House of Representatives, investigated by the FBI; theaters refused to play it and it was widely denounced by newspapers and chambers of commerce throughout New Mexico.

It was rediscovered by Chicano Movement activists in the late 1960s and remains today a neo-realist classic for its focus on Chicano activism and feminist politics.

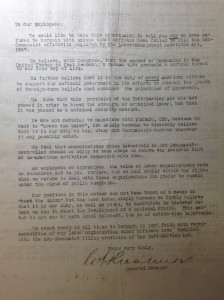

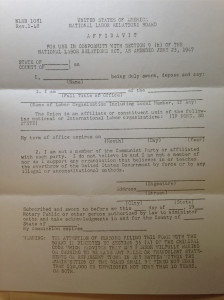

The strikers found success in the film but the real union found little more than struggle. Mine-Mill Local 890 organizer Clinton Jencks was arrested by federal agents in 1953 and jailed for alleged communist connections. The Kennecott Copper Company refused to negotiate with Mine-Mill Local 890 in the mid 1950s, telling the union’s members “we have refused to bargain with unions whose officers have failed to file the non-Communist affidavits required by the Labor-Management Act, 1947 [Taft-Hartley]. We believe, with Congress, that the spread of Communism in the United States is fast becoming a menace that presents a serious threat to our free way of life.”

Apparently, Kennecott defined “freedom” as its ability to reap windfall profits while its workers, on whose backs it made those profits, labored in miserable working conditions for immiseration wages. Kennecott Copper Company was the world’s largest copper producer with mines in the US and Chile. Its domestic production at four mines in Arizona, Nevada, Utah and New Mexico accounted for nearly half of all copper produced in the US and 20 percent of the world’s copper supply. The mine in Bayard was the largest industrial operation in New Mexico and accounted for 12 percent of Kennecott’s total copper output. In the years prior to the “Salt of the Earth Strike”, and despite a series of strikes that shut down mines in Utah, Kennecott reported more than $23 million in profit. It had $17 million dollars on hand in reserve and reported to its board of directors an earned surplus of nearly $165 million of accumulated profit.

While the mine recorded record profits throughout the 1940s and 50s, most Anglo workers at the mine made less than $5 per day. Kennecott paid lower wages to Spanish-speaking and Navajo workers.

Mine-Mill merged with the United Steelworkers of America in 1967, the same year that Local 890 staged a six-month strike at the mine in Bayard. Kennecott sold the mine to Phelps-Dodge in 1987. In the dramatic history of violent struggle between mining companies and miners’ unions, Phelps-Dodge stands out as among the most aggressive union busting firms in US history. After thousands of workers lost their copper mining jobs in the early 1980s, and Phelps-Dodge refused to negotiate with the Steelworkers, thousands of union miners walked out of four of Phelps-Dodge’s Arizona mines. Phelps-Dodge responded by firing workers and evicting others from company housing. Local police arrested workers for walking legal picket lines and Phelps-Dodge hired goons who violently attacked the strikers who remained.

Phelps-Dodge broke the union in 1984 when the Arizona National Guard, with tanks and helicopters, attacked strikers and helped thousands of scabs cross picket lines throughout Arizona. The year after breaking the union, Phelps-Dodge, which had refused a small cost-of-living increase for union workers during negotiations in 1984, reported more than $200 million in profits in 1985, an increase of more than 600 percent over 1984 levels.

In the late 1990s, Phelps-Dodge built a private security army in Arizona and used it to attack union workers. It fired or suspended dozens of workers in New Mexico for once holding a peaceful protest at a company banquet.

Phelps-Dodge sold the New Mexico mine in Bayard to Freeport-McMoRan in 2007. It is unsurprising that after generations of union busting, it would be Freeport-McMoRan that would finally break the union at the Bayard mine. Freeport-McMoRan is one of the world’s wealthiest corporations with a documented history of ultra violent and often successful union busting campaigns.

It employs 23,000 workers at its massive Grasberg mine in Indonesian Papua, where workers are paid U.S. $1.50 an hour. In 2012, rebels linked to the Free Papua Movement (Organisasi Papua Merdeka, or OPM) began targeting Freeport managers and facilities as part of a decades-long struggle for an independent Papua. The attacks came on the heels of particularly contentious labor struggles at Grasberg where workers demanded modest wage hikes. When labor negotiations stalled, thousands of miners went out on strike. The peaceful strike quickly turned violent when Freeport brought in bus loads of scabs. Strikers defended themselves against an army of more than 500 Freeport security thugs who swept through the protest firing shotguns, killing one union striker and wounding six others.

Despite Freeport’s violent suppression of local labor, and its decades-long complicity propping up Indonesia’s brutal Suharto regime, it is the separatist OPM that the US Department of Homeland Security considers a terrorist threat.

Occupy Phoenix activists marched on Freeport’s Phoenix headquarters in October of 2012 to protest the killing of striking miners at the Grasberg mine. The same month President Obama reaffirmed US support for the Indonesian police state in Papua during a visit to Jakarta in which he committed US marines to the region, a move that the Thai newspaper The Nation concluded had everything to do with heightened concerns over security at the increasingly volatile Grasberg mine.

While Papuan miners defended a picket line against Freeport’s private police force, 1,200 miners at Freeport’s Cerro Verde Mine in Peru walked off the job. Freeport bought Cerro Verde in 2007 and along with gold, silver, uranium and molybdenum, it produces 2% of the world’s annual copper production, more than 200 million pounds of copper each year from a massive open pit mine and huge leaching facility. Freeport-McMoRan reported 2011 revenues of nearly $21 billion with profits in excess of $5 billion; meanwhile miners not only in Peru and Indonesia but more recently in Chile, Bolivia, Mauritania, South Africa and Zambia ask for modest pay increases and get instead guns and goons.

Freeport-McMoRan took a different approach to union busting in New Mexico than it has in Indonesia. It began by paying higher non-union wages to employees of its three mines in southern New Mexico, a fact Irvin Shane Shores noted when asked why he began the decertifying campaign. What Shores didn’t say was that the Company was also paying non-union workers bonuses.

There has been some speculation that Freeport-McMoRan recruited Shores expressly for the purpose of busting the union. This is a familiar union-busting tactic. Shores of course denies this. Any connection between Shores and Freeport-McMoRan would invalidate the decertification vote. Prior to coming to Freeport-McMoRan, Shores had never worked in a mine. He managed a Pizza Hut in Deming and, more recently, owned a doughnut shop that he quickly ran into the ground. In 2009 Shores unsuccessfully pursued a seat on the Luna County Board of Commissioners as an ultra conservative Republican.

He makes up for his lack of mining skills with a crusading anti-union enthusiasm that surely appealed to Freeport-McMoRan.

Guadalupe Cano, the granddaughter of a former Mine-Mill union leader expressed outrage at Shores and the decertification vote, telling the Silver City Daily Press, “I am absolutely horrified. I cannot believe that after all of these generations of people fighting for this union that it is all gone after one man, who hasn’t even worked there long, decided it should go away. I’m glad my grandpa didn’t live to see this day.”