Over 100 demonstrators stood at the doors of the Connecticut Superior Court at Meriden on August 14, in a demonstration demanding an end of state judicial cooperation with the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, sponsored by the Connecticut Immigrants Right Alliance (CIRA), a statewide coalition organizing for the human rights of immigrants.

At the center of the issue is the Transparency and Responsibility Using State Tools (TRUST) Act, a state law first passed in 2013 and extended in May of this year. The act mandates that a judicial order is required for police in the state to hand someone over to ICE, with two exceptions: individuals who are on a federal terrorist watch list and those who have committed a major felony.

Often ICE uses civil immigration detainers instead of judicial orders signed by a state or federal judge in order to convince police, prison staff or other authorities to detain someone until the agency can pick them up.

An updated version of the TRUST Act, state Senate Bill 992 (SB992) was passed in May 2019 and is set to take effect on October 1. SB992 annuls a number of exceptions held by the previous act and expands on privacy protections. However, the current law and current tenor of the Trump Administration’s continuing crackdown with an election year have combined to allow state courts to become a hunting ground for ICE agents.

“Over the years we learned the exemptions were being used as a loophole and abused by the same judicial marshals in this courts,” said CIRA organizer Jesus Sánchez, “The new TRUST act will prevent a lot more families from being taken away.”

CIRA and its coalition partners unveiled a list of demands, including: termination of judicial marshals who enable ICE raids and apprehensions in state courthouses, reparations for victims of judicial marshals cooperating with ICE, establishment of stronger sanctuary city policies in Connecticut cities and towns, banning ICE from entering state courthouses and making the TRUST act extension (SB992) effective immediately, instead of on October 1.

Protesters cite an incident that happened at this courthouse last year as a driving force behind their demands. On December 13 2018, ICE agents took New Haven resident Elias Robledo into custody after he had been held by judicial marshals in Meriden. As he was being dragged away in front of his children, Meriden City Council member Miguel Castro tired to shield one of Robledo’s daughters from the harassment of public safety officers. Castro was charged with the alleged assault of two judicial marshals and inciting a riot. He was among those at the demonstration Wednesday standing in protest.

“The bad behavior and hatred of these marshals and the misconduct of these marshals have caused hardship,” Castro told the protesters. “The judicial system and its representatives must be fair and impartial. Otherwise, the people are denied their fundamental constitutional right to due process.”

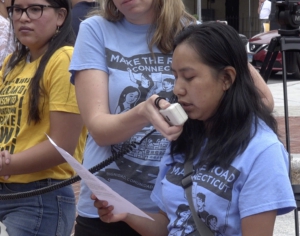

Amid calls to fire judicial marshals who have openly aided recent ICE raids in the state and “Down! down with deportation!” other speakers relayed similar stories. Rosario Tepoz, a local advocate with Make the Road Connecticut, shared what happened when her young son was separated crossing the border from Mexico to the United States in 2012. “He was four years at the time. He [was] detained for two weeks all by himself,” Tepoz said. “Families like mine all across Connecticut are still separated like this today.”

Jason Ramos, whose family was under threat of deportation a few years ago, relayed what he experienced while working at the consulate of Ecuador during earliest seeds of the current growing crackdown. “I saw firsthand how ICE, through the judicial marshals, the probation houses and the police have been deporting people without any shame,” Ramos said. “We have to hold the authorities accountable. Just because they have a badge doesn’t mean they are looking out for us.”

CIRA and its coalition partners seek to expand the protests across the superior courts in Connecticut and gain public support for their demands. Representative for the court system have stated that taking the actions from the demand would “politicize” the process.

“The judicial branch says they cannot do certain things because that would constitute political action,” Rivera-Forastieri noted, “Our belief is by not doing anything at all, they are making a political decision that they are okay with this kind of violence happening around our state.”