The community of Crown Heights, Brooklyn, held a vigil and march on April 4 to continue the fight for justice for Saheed Vassell and his family. They marked the year anniversary of Vassell’s killing by police, and protested the recent announcement by State Attorney General Letitia James that she will not seek indictments against the officers responsible for his death.

Vassell, who lived with Bipolar Disorder, was well known in his community. He could often be found sitting outside the community barbershop, available to do odd jobs. On April 4, 2018, an unknown person called 911, because Saheed was walking down the street, “pointing something at people.” Multiple witnesses confirm that plainclothes undercover officers just jumped out of their car and killed him. Police gave no warnings and issued no commands before firing 19 shots.

While Saheed’s story is not uncommon for Black people who encounter the police, he is also an example of the excessive forced that is used against mentally ill and/or disabled people when police are designated first responders. The police are not trained to handle mental health crises or emotional disturbances, and they often use excessive force when responding to these types of emergencies.

Police killings of disabled people: A shameful national epidemic

In the past nine months, New York has seen seven incidents of emergency calls involving people in emotional crisis resulting in their being shot dead by the police. But this is not just a New York problem. It is a national epidemic.

Nearly half the people shot by police in Maine between 2000 and 2011 had a mental illness.

Almost 60 percent of people killed by police in San Francisco between 2005 and 2013 had a mental illness that “was a contributing factor in the incident.”

Roughly a-third-to-a-half of all people killed by police in this country are disabled, according to the Ruderman Foundation. What does this mean in numbers? In 2015 and 2016 combined, nearly 500 people with mental illness were fatally shot by the police. Those with untreated mental illness are 16 times more likely to be killed during a police encounter than other civilians approached or stopped by law enforcement, according to the Treatment Advocacy Center. In many cases police were responding to requests for assistance from family or neighbors to get mental health care for the person.

Police not punished

Many are aware that this is a big problem. Since 2013, local organizations and elected officials in New York City have been pushing to train police in crisis intervention. While this would merely be a reform of the unjust criminal justice system, the city government is dragging its feet on implementing even this. The city has not trained many police, and those trained in crisis intervention are very often not the the first cops to respond to a crisis. Meanwhile police who kill people in emotional crisis are neither held accountable nor punished.

Another New York family whose disabled son was killed New York City police recently received some news from the state. Mohamed Bah was wrongfully killed by cops in 2012 while in emotional crisis after his mother called 911 to get him help. Last month Hawa Bah, Mohamed’s mother, was awarded a settlement from the city and an admission that her son was wrongfully killed. A 2017 jury even found the cop, Edwin Mateo, liable for using excessive force. Both these things are very unusual. Yet Mateo still has his job, and is drawing a paycheck!

Ms. Bah does not trust the police at all. She explained, “The NYPD showed up at Mohamed’s apartment with heavy weaponry like they were going to war. They broke down his door even though I told them to go away because I wanted an ambulance. Since then, the NYPD’s Crisis Intervention training has been proven to be totally ineffective. In Mohamed’s name, I am fighting for the NYPD to be eliminated as first responders to people in emotional crisis, like my son was. I do not want any other mother or family to have to face the suffering I have had to endure. I want future generations to benefit from Mohamed’s legacy.”

The police often receive mental health symptoms as threats and react violently, and this is exacerbated when the person is Black. The combination of white supremacist fear and the unpredictability of an emotional crisis often leads to deadly outcomes for Black and/or disabled community members. This is why alternatives to police response has been a popular topic of conversation among community members and around the country. Those voices from deep in the community call for banning the police from responding to a mental health crisis.

Community control sorely needed

Chauvet Bishop, a healer and Crown Heights community member, believes that police should not be involved in responses to mental health or emotional crises at all. “The NYPD should not react to these situations. Emotional responders, who are trained to de-escalate these situations, should be the first responders. It is not necessary to have the police involved.”

What Chauvet is referring to is often called a 911 diversion program, which has been implemented in communities around the country. One Minnesota county has implemented a Crisis Response Unit to intervene during mental health crises. “The Crisis Response Unit has 20 full and part-time social workers housed within the Washington County Sheriff’s Office. The CRU has been called “a brand new approach to quickly and effectively help people at perhaps the worst time in their lives”

A real revolutionary solution would involve both community organization and the dismantling of the police state. Alternatives could include community members intervening in emotional crises. Bishop states, “The community can help avoid murders like Saheed’s by not calling 911, but seeking to de-escalate the situation and maintain a sense of community and humanity.”

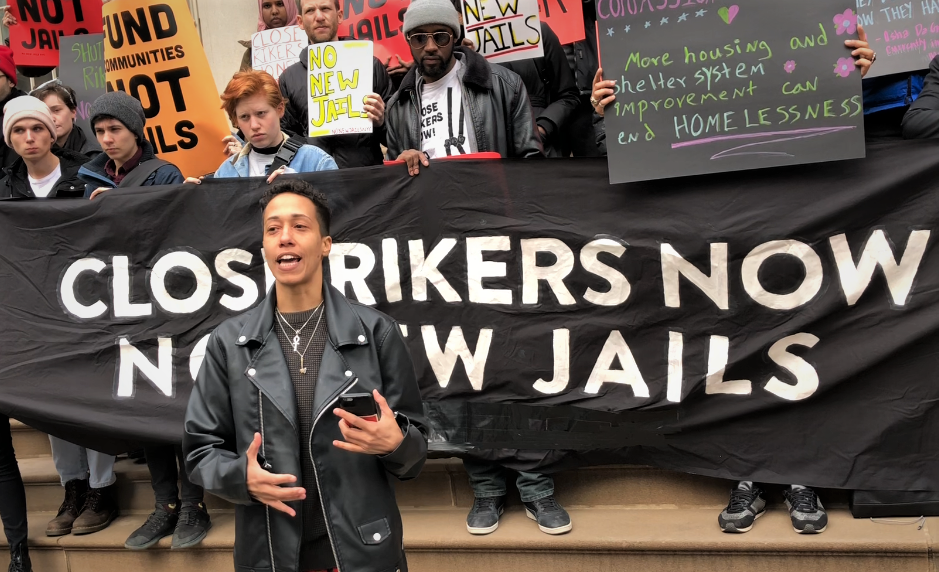

Bishop, an advocate of community control, works with the Audre Lorde Project, which offers de-escalation services and mental health first aid training. Bishop also works with the No New Jails Coalition, which seeks to use take back the $11 billion the city intends to spend on new jails and use that money social programs.

Another idea is a 911 diversion program that includes a 24 hour mobile crisis unit, referral to mental health services and follow up after the crisis has been resolved. These solutions offer a safer and more humane response than subjecting people to the murderous police state.

With a more revolutionary response, lives like Saheed Vassell’s can be saved and we can begin to dismantle the racist, ablist police state.