Photo: 2019 meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee. Public domain.

Every young person in America is taught in school about the wonders of the U.S. system of government — brilliantly designed to protect freedom, flexible enough to solve any problem, and given legitimacy by the consent of the governed. But this fairy tale version of U.S. politics bears no resemblance to reality.

In fact, these notions might seem so outlandish that many people’s eyes glaze over at the mere mention of the intricacies of how the government functions. But for those who want to put an end to this unjust order, it is absolutely essential to understand those intricacies. It is not necessary to grasp the ins-and-outs of the Constitution or the legislative process to come to the conclusion that the system has to end — but to actually bring about this profound transformation of society, we need to know in detail how our enemy operates.

Liberation News is producing the “Civics Class for Radicals” series to shine light on the reality of this system of government of, by and for the rich.

The Federal Reserve – known as the Fed for short – is an indispensable tool for the big Wall Street banks to exercise their dictatorship over the economy. From top to bottom, it is a structure dominated by finance capitalists that wields huge power with a minimum of democratic oversight. In recent months, this institution has moved to political center stage as its controversial policy of hiking interest rates threatens (and is in fact designed) to create mass unemployment.

If you ask Fed officials what their mission is, they would cite the “dual mandate” of ensuring price stability and maximum employment. But this masks the true character of the Fed and obscures the specific powers it wields. It is also incorrect to suggest, like many libertarians do, that the Federal Reserve itself is the dominant force in the economy, using its centralized authority to unfairly distort the functioning of “the market.”

The Fed is in fact an instrument for the capitalist ruling class to manage the turbulence of their system in a way that allows the biggest corporations to make the greatest profits possible. And it has been that way from the very beginning.

The Jekyll Island conspiracy and the birth of the Fed

Having a centralized, national bank backed by the government has been a long standing goal of at least parts of the ruling class. This was particularly true of those most connected to modern commerce and the world market and with the clearest consciousness about the path towards developing the still-early capitalist system of production. The first attempt came in 1791, when the First Bank of the United States was created with the purpose of making loans for public and private ventures and handling government revenue. When the First Bank’s charter from Congress expired and needed to be renewed in 1811, the bank’s opponents were able to block it. A Second Bank of the United States was revived in 1816, but it too did not secure a renewal of its charter and went out of existence in 1836.

The idea of a central bank found its strongest support among the section of the elite based in the Northeast, where wealthy merchants dominated and would stand to benefit the most from the bank’s activities. Among the elite involved in agricultural production, where the slave owning class dominated, the proposal was more skeptically received. These forces were even worse than the banks’ supporters, and sought to hold back the tide of development to safeguard their own power. The grievances of small farmers and others in society were also harnessed by opponents of the bank like President Andrew Jackson, who led the effort to eliminate the Second Bank.

Today, central banking is something that is universally accepted among the capitalist class the world over. But capitalism itself changed and developed over time. Capitalism emerged alongside (and intertwined with) earlier models of exploitation like slavery and feudalism, and its growth was dependent on the development of technology that would facilitate large-scale industrial production. It was only with time that large corporations were able to crowd out small producers – large corporations that in turn became subordinate to the financial capitalists running the big banks. As capitalism matures, the need for a central bank becomes more and more obvious to those tasked with managing the system.

One feature of capitalism that becomes more prominent as it matures is financial crises. Especially during the “long depression” of the 1870s through the 1890s, banking “panics” took place periodically, but there was no one government agency designed to respond.

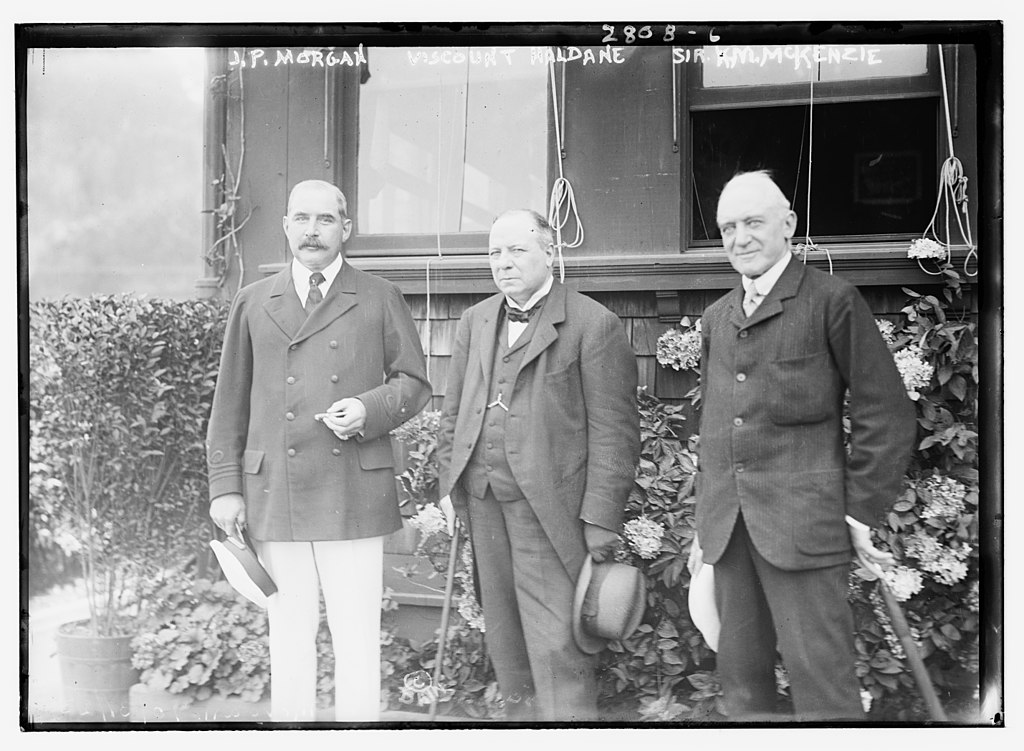

During the Panic of 1907, JP Morgan — far and away the most powerful finance capitalist of the time — had to essentially solve the crisis himself. During banking crises, a large number of depositors all attempt to withdraw their holdings at once, such that the bank does not actually have enough money to process these withdrawals and collapses as a result. Banks only keep a fraction of their deposits available as cash (the “fractional reserve system”) and use the rest to make investments and issue loans. JP Morgan had to use his own bank’s money to make deposits in weaker banks to prevent them from collapsing, and convened the other big financiers of the era to do the same. Morgan had to perform a similar rescue operation in 1895.

For the capitalists, having to individually handle crises like these defeats the purpose of having a state in the first place. Instead of having to use their own money at their own risk and accept the political exposure that comes with direct personal involvement, the capitalists would much rather have the government shoulder this burden in the name of “the public”.

So shortly after his intervention in the Panic of 1907, JP Morgan got to work on the creation of a government institution that would do just that. Several years of efforts culminated in 1910 on Jekyll Island – a ruling class resort off the coast of Georgia owned by Morgan. Six powerful ruling class figures gathered there in total secrecy to draw up legislation to create the Federal Reserve. They were so concerned with keeping their plot hidden from the public that this grouping is referred to as the “first name club” – participants could not refer to any other attendee by their last name, so that the servants accompanying them did not piece together the magnitude of the gathering that was taking place and tell others.

Although Morgan’s trusted lieutenant Henry Davison was present, Morgan himself did not preside over the Jekyll Island meeting. That role fell to Nelson Aldrich, one of the most powerful Senators of his era. Aldrich was a loyal ally of the big banks, and his daughter was married to the son of John Rockefeller, the wealthiest capitalist to ever live. Aldrich’s grandson was four-term New York Governor and Vice-President of the United States Nelson Rockefeller.

Aldrich took the proposal developed at Jekyll Island and shepherded it through Congress. While it was modified during this process, the core of what the conspirators at Jekyll Island envisioned finally came into being in 1913 with the passage of the Federal Reserve Act. The true origin of the concept was unknown to the public until years later, long after the act had passed (and after first name club member Paul Warburg had become Vice-Chairman of the Fed).

How the bankers rule the Fed

Sometimes, the capitalist class rules society through open, undisguised dictatorship. But a much more stable form of capitalist rule involves “democratic” practices that make it appear that the state is legitimate and rules by consent — when there are in fact a whole range of formal and informal mechanisms available to guarantee that the government always fundamentally represents the collective interests of the capitalist class. This is the basic approach guiding the organizational structure of the Fed.

The Fed is composed of 12 regional reserve banks, headquartered in different parts of the country and referred to by the city where they are located. Each reserve bank is run by a Board of Directors, which chooses one member to serve as its executive Governor. One third (Class A) of each bank’s board is directly composed of representatives of private banks — not exactly proportional to bankers’ share of the population, but still it allows apologists for the system to point out that this is not a majority. Another third (Class B) of a regional board of directors are meant to represent the interests of the public, but the public does not get to decide who they are. Instead, members of Class B are chosen by … the private banks! The only requirement is that Class B directors not currently work for a bank — for instance, a banker’s buddy from the country club who’s a tech executive would qualify as a suitable defender of the public interest.

The final third of regional bank directors also theoretically represent the public and are appointed by the Federal Reserve’s Board of Governors — the national leadership of the Fed. The Board of Governors is composed of seven members who are nominated by the president of the United States and confirmed by the Senate. While the presidency and the Senate have profoundly anti-democratic qualities (at the time the Fed was conceived the Senate was not even an elected institution), it does provide a modicum of public involvement in the process. To counteract this, members of the Board of Governors are given extremely long, 14-year terms in office. The goal of this, similar to the lifetime appointments served by Supreme Court justices, is to make Governors “apolitical” — soberly chosen to look after the long-term interests of capitalism, with less incentive to take actions that would be supported by the majority of people.

The president nominates one member of the Board of Governors to serve as the Chair of the Fed for a four-year term, and another to be its Vice-Chair. Both nominations have to be approved by the Senate, and Governors can be re-nominated to serve additional terms as Chair or Vice-Chair. If a Chair’s four-year term expires before their 14-year term on the Board of Governors is up, then they go back to being a regular member of the Board.

Of the 16 Chairs that the Fed has had in its history, 10 were themselves finance capitalists. Of the six non-bankers who were appointed to the role, two were CEOs of major corporations, and one (Alan Greenspan) grew rich running a consulting firm hired by some of the biggest companies in the country. Current Fed Chair Jerome Powell was an executive at a number of finance firms starting in the 1980s. This includes a stint as a partner at The Carlyle Group, one the largest private equity firms in the world with hundreds of billions of dollars of assets.

Interest rates and the Fed

Among the specific powers of the Federal Reserve, perhaps its most prominent relate to interest rates. The Federal Reserve does not dictate the interest rates charged for loans given out by private banks. But the Fed is able to influence this through “open market operations” – buying and selling financial assets, mainly bonds issued by the government, in quantities large enough to affect overall conditions in financial markets.

The Fed sets a target range for an especially influential interest rate called the Federal Funds Rate. Practically speaking, this is the interest rate that banks pay to take out very short-term loans to satisfy the requirement that they keep an amount of cash in reserve equivalent to a certain percentage of total deposits they hold. But the Federal Funds Rate’s main power comes from its status among the big banks as a universally-recognized indicator of how much to charge for private loans. If the Fed Funds Rate goes up or down, then typically interest rates across the board follow suit.

Decisions about interest rates are made by a body of the Fed called the Federal Open Market Committee. This is a 12-member grouping that holds several high profile meetings a year, which are significant both for the decisions that they make and any public statements made at the conclusion that indicate the Fed’s future course of action. The FOMC is made up of the seven members of the Board of Governors, and four regional reserve banks Governors chosen on a rotating basis who serve one-year terms. The 12th member is always the Governor of the New York Reserve Bank, which is given special status as the home of Wall Street. In addition to interest rates, the FOMC also has the power to make other important decisions about the assets owned by the Fed.

Currently, these 12 individuals are on a mission to intentionally crash the economy by increasing interest rates. Lowering interest rates tends to make economic growth speed up because it is easier for companies and individuals to take out loans and engage in new ventures. Raising rates makes the economy slow down because it is more costly to take out loans for new projects. If the rate hikes are extreme enough, it can even cause a recession.

While a recession is typically the last thing the Fed wants, this situation is different because of the inflation crisis and because it has generally become very easy for workers to find a job. In an economic crash, inflation comes down because workers lose their job or at least part of their income and are therefore unable to spend to the same extent. This means overall demand for goods and services becomes greatly diminished, and prices eventually fall. Of course this involves major suffering for working people, but to the Fed that is a small price to pay.

The Federal Reserve and the capitalist class as a whole is also very eager to create a “looser” labor market – meaning that they want to make it much harder for workers to find jobs. If it is harder to find work, then people will feel compelled to accept lower wages. Lower wages means higher profits for the capitalists, and a scarcity of jobs also has the effect of tamping down workers’ confidence to struggle for a union or go on strike.

Bailouts: Putting capitalism on life support

The Federal Reserve’s desire to induce a recession is the result of extraordinary circumstances – usually the Fed is focused on keeping capitalism from sinking by providing various forms of support to the big banks and corporations. For instance, the Fed kept interest rates extremely low – essentially at 0% – for years following the Great Recession. Other central banks, like the Bank of Japan and the European Central Bank, have even offered negative interest rates that require less than the full value of a loan be repaid.

When low interest rates are not enough, the Fed has in recent years turned to a maneuver referred to as Quantitative Easing. QE is essentially when a central bank decides to buy a certain amount of a particular financial product in order to inject cash into the system. The Federal Reserve can own assets just like any other bank, and beginning in December 2008 it started purchasing hundreds of billions of dollars of a type of asset called mortgage-backed securities as well as Treasury bonds. Various iterations of Quantitative Easing were implemented until 2015. By that point, the Fed had accumulated $3.6 trillion worth of these products, purchased to stimulate the financial markets and keep Wall Street afloat.

When the Coronavirus pandemic broke out, the U.S. government focused first and foremost on protecting corporate profits. This involved a provision in the CARES Act – the emergency economic stimulus package passed at the end of March 2020 – for a bailout fund that could disburse trillions of dollars with the help of the Fed. The CARES Act allocated $454 billion of money to the Treasury Department to provide emergency loans to corporations. This is an enormous sum of money, but the bailout’s true size was really closer to $4.5 trillion since the Fed had authority to give out nearly ten dollars of support for every dollar allocated to the Treasury.

After Silicon Valley Bank collapsed in March – and triggered a chain reaction that claimed Signature Bank, Silvergate Bank and Credit Suisse – the Fed once again lept into action to safeguard big finance. It unveiled a new bailout fund called the Bank Term Funding Program, which major financial institutions can use to take out billions of dollars of one-year loans under favorable terms. And the Federal Reserve stands ready to provide support to the big banks at an even more massive scale should the instability spread further.

While the very existence of a central bank was controversial at first, the Federal Reserve has now become an indispensable pillar of modern capitalism. Fed support is part of the lifeblood of today’s Wall Street, keeping the big banks alive as they engage in increasingly complex and reckless gambling in the never-ending pursuit of higher and higher profits. When times are tough, workers are on their own to fend for themselves. But the capitalist class can always count on the support of their ever-loyal friends at the Federal Reserve.