“The Holly: Five Bullets, One Gun, and the Struggle To Save an American Neighborhood,” by award-winning investigative journalist Julian Rubinstein, tells Terrance Roberts’ story: a Black man growing up in a community struggling with horizontal violence, economic underdevelopment, and violent, racist policing. It seeks to answer why Roberts, a famed anti-gang activist, shot someone at his own peace rally in September 2013.

In the context of last fall’s attack on Denver and Aurora protest leaders, it also serves to educate the movement in Denver. This matter is as relevant as ever — the machinations of the police to infiltrate and destroy the Black community and movements for Black liberation.

Roberts, an organizer with the Frontline Party for Revolutionary Action, was arrested on Sept. 17, 2020, alongside Party for Socialism and Liberation organizers Lillian House, Joel Northam and Eliza Lucero. All four were leaders of the unprecedented, large-scale protests against police terror in Denver and Aurora just months before. For leading peaceful protests they were charged with crimes carrying decades in prison, and they continue to face multiple charges and a lengthy legal fight.

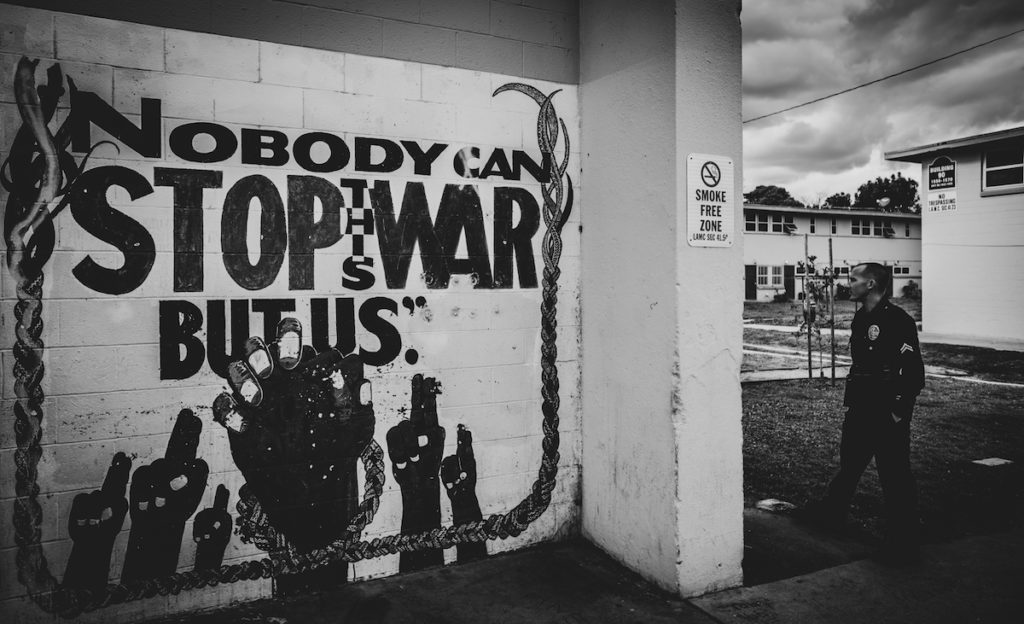

‘Nobody can stop this war but us’

Roberts’ 2013 peace rally was an effort to bring the community of Northeast Denver together and to promote unity between the city’s Bloods and Crips to curb the violence that had risen over the previous summer. Roberts had joined the Bloods in the late 1980s and left in the early 2000s. He recognized that community violence needed to be solved at the root. Black youth needed to be given economic and social opportunities in their own neighborhoods that years of underdevelopment did not allow. He had founded and helped build these opportunities through development in his neighborhood, The Holly, as well as through his gang interruption program, The Prodigal Son Initiative.

Unlike mainstream “anti-gang” programs in the city, Roberts had no interest in working with the Denver Police Department. Inspired by the famed mural in the Nickerson Gardens in Watts, Los Angeles, Roberts believed “nobody can stop this war but us.” This attitude of self-reliance and pride (reminiscent of one of the original groups to earn the FBI label of “gang,” the Black Panthers) gave Roberts a vision. At first, he was welcomed as an innovator by politicians, police, and property developers. But as he grew to assert his independence against interests that harmed or sidestepped his community, Roberts became first an outcast and then an enemy.

At his rally in 2013, Roberts was attacked by a crew of Bloods, one of whom he shot in self-defense. While the media, the police, and the city immediately went to work constructing their story of “backslid former gang member shooting to kill at his own peace rally,” Roberts was certain he knew what had happened.

He had watched over the years as DPD and other law-enforcement constructed an “urban war industrial complex” to use and perpetuate gang violence for their own ends. They cultivated supposed “anti-gang” initiatives with charismatic leaders who were happy to work with DPD. The police brought gang members into their networks by offering reduced sentencing, cash payments, and other gifts.

Alongside this, real-estate developers hungry to gentrify Black communities like The Holly capitalized on the aggressive, destructive policing and police-informant-fueled gang violence to push Black Denverites out of their homes.

Roberts was slandered in local and national media as “the anti-gang activist who shot someone at his own peace rally.” He was eventually acquitted of all charges related to the shooting.

In “The Holly,” Rubinstein begins with a single question: Did this network of police-driven anti-gang workers, informants, and real-estate developers conspire to put Terrance Roberts in prison, if not to murder him?

From Panthers to Bloods

As the backdrop to Terrance Roberts’ story, author Julian Rubinstein traces a timeline unknown to many. That is, the parallel fall of the social movements and civil rights groups of the 1960s and the rise of street gangs in the 1970s. In LA, racist white supremacist gangs and their violence spurred the creation of Black gangs in self-defense in the 1950s and 1960s, which in turn developed their own rivalries.

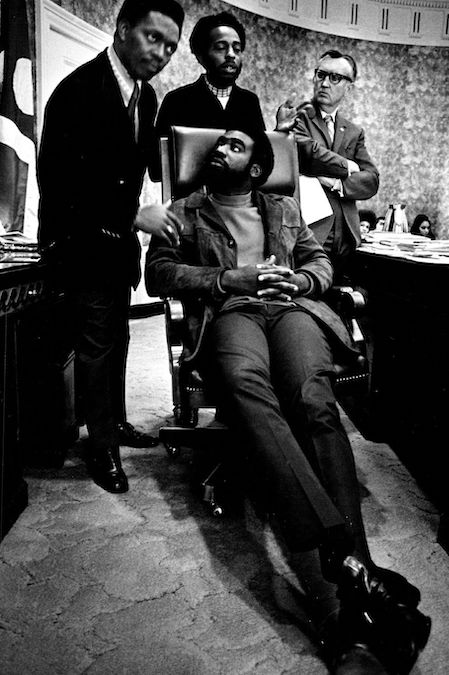

Some within the gangs had connections to the Black liberation movements of the 1960s and 1970s. Raymond Washington, the founder of the Crips, had been radicalized as a youth in a group adjacent to the Black Panthers. Then, in 1969, Bunchy Carter, a former gang member who had become a pillar in the LA Panthers and hero for the youth of his community, was assassinated in an FBI-fueled rivalry between the Panthers and the US Organization. Washington saw the Black community struggling with economic underdevelopment in South LA. He saw the lack of leadership after COINTELPRO crushed the Panthers and led to assassinations like Carter’s. So he founded the Crips as an attempt to protect his neighborhood.

In Denver, Crips founder Michael Asberry’s father was a classmate of Lauren Watson, the founder of the Denver Black Panther Party. Terrance Roberts’ father George Roberts was friendly with Huey Newton when the two lived in Oakland. The Denver Panthers chapter, like those across the country, was mercilessly attacked and surgically dismantled using trumped-up charges against leaders and COINTELPRO infiltration.

This destruction of Black community groups and political parties, along with years of underdevelopment in communities like The Holly, led to abysmal economic conditions. Then the crack epidemic, again fueled by the U.S. state, hit Denver in the 1980s. It was within this context that Roberts, Asberry and others began to construct Denver’s gangs.

‘The war on gangs’ and COINTELPRO

The Denver Police Department, like departments across the country, found the crisis of gang violence in Black communities to be a lucrative opportunity to expand their arsenals and to receive huge amounts of federal, state, and local money. With the rise of the Bloods and Crips in the 1990s in Denver, DPD was able to gain access to massive federal law enforcement grants created by the Clinton Justice Department, and Congress members like Joe Biden and former Hillary Clinton VP-pick Tim Kaine.

The “war on gangs” meant millions for the police. It also meant millions of Black youth stuck in the criminal justice system. A huge, militarized police presence lorded over Black communities like The Holly. And with few other economic or social opportunities, Black youth were quickly drawn into an organization like the Bloods or the Crips, one of the few avenues offering some level of protection, opportunity, and prestige.

Solutions from within Black communities to the growth of gangs — violence interruption, youth diversion programs, economic opportunities — were common sense. They also saw major results. But these community-based solutions did not generate enormous police budgets and colossal private prison contracts.

Police found it far more lucrative to pursue resource-intense “gang reduction programs” by creating networks of informants and infiltrators. In reality, the main product of these programs is not a reduction in crime but an ever-expanding network of active gang members acting as spies and operatives for the police within their own communities, while empowered to commit crimes with virtual immunity.

Roberts started his Prodigal Son Initiative in this environment. Rubinstein traces a complicated network of “impact players” turned informants, OGs perpetuating violence with police immunity and even assistance, and “anti-gang activists” that seem at times to be another layer of information-gatherers for the Denver police.

The deep web of police infiltration, including the ties between the gang members that attacked Roberts and prominent Denver developers, is not fully illuminated by the end of “The Holly.” Rubinstein’s artful investigative journalism only begins to pull the cover back on the full extent of corruption in Denver — but much is yet to be unearthed.

Our movement would do well to remember that COINTELPRO only began to be revealed after activists broke into an FBI field office and stole over a thousand pages of documents. Even today, we are learning more about the extent of this national program of infiltration, deception, illegal monitoring, and overt force.

‘The Holly,’ a must-read for organizers confronting the power of the police

The Sept. 17, 2020, arrest of Terrance Roberts and PSL organizers Lillian House, Joel Northam, and Eliza Lucero should be seen as a continuation of police and U.S. state attempts to destroy progressive movements. Just like COINTELPRO, we are now learning more and more about the surveillance, attempts to undermine and split the movement, and infiltration during the summer of 2020 uprising against racism in Denver. Similar to the sanitized, state-funded “anti-gang activists,” Denver saw attempts by the police and the city to co-opt the leadership of the uprising with mis-leaders.

And like “The Holly” peaks with an overt attack, an act of desperation by state agents to kill or jail Terrance Roberts, the massive protest movement in Denver last year was followed by a vicious, and continuing, attack in the courts.

“The Holly” is a book that should be written about every city. It is a fearless dive into the stories of oppressed people in Denver. It carefully constructs the backdrops of purposeful economic underdevelopment, the destruction of organizations like the Panthers, and the growing power of the police and criminal justice system to tell its story. It honestly shows a collection of struggles still in motion.

The story within the book is destined to be incomplete, as it has not ended. “The Holly” seeks humbly to answer one question, but it achieves much more. It provides a valuable education to a young movement about the power of the state and its many arms, and gives hope that those struggling for justice can fight, and can win.

You can pre-order “The Holly” here.