The International Longshore and Warehouse Union shut down 29 west coast ports on June 19 in remembrance of George Floyd and to mark Juneteenth. All along 2,000 miles of coastline, from Seattle to San Diego, not one container was loaded or unloaded.

The ILWU has a long history of anti-racist and international solidarity. It shut down these ports in 1968 after the death of Martin Luther King, Jr. Union members refused to unload ships from apartheid South Africa in the 1960s, 70s and 80s. The ILWU closed West coast ports to oppose the Iraq war in 2008. It shut them down again in 2010, responding to a call for solidarity from Palestinian unions, and refused to unload Israeli ships in 2014. Earlier this month longshoremen held an 8-minute work stoppage to demand for justice for George Floyd.

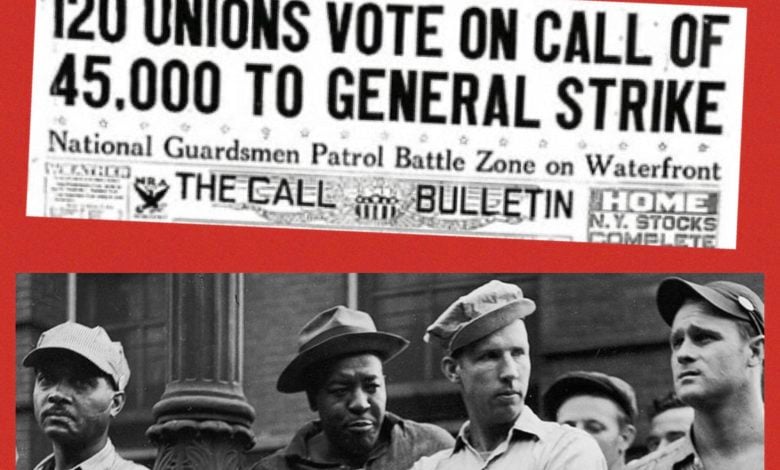

This tradition of solidarity came from a historic union struggle in 1934, when dock workers struck for 83 days, culminating in a 4-day general strike in San Francisco. Building anti-racist solidarity was key to their win, and to ending some of the worst working conditions in the country.

One giant shape-up

Did you ever “shape-up” looking for work? That’s when you go to a workplace and stand and wait for hours. Eventually the foreman comes out and says “I’ll take you, you and you ….” and then goes back in; maybe he comes out a few hours later and picks a few more, telling the rest to “go home now, I don’t need you.” This is what life is like for so many undocumented workers today.

This was life on the ship yards in the 1930s for all longshoremen. If you didn’t give the foreman part of your pay when he picked you, or you didn’t buy him a drink when you saw him in a bar, or if you ever complained about anything, you might never get picked for work again. You might wait all day and then go home hungry and humiliated.

If you were African American and showed up looking for work, the company goons would likely beat you up before sending you home, as the docks were segregated.

In addition to the daily shape-up, when a ship docked, a group of longshoremen was hired to stay on the ship as it went from port to port on the West Coast, loading and unloading cargo. The workers ate and slept on board. They had no toilets or bathing facilities. They only got paid for the time actually working cargo. Safety was nonexistent and accidents were common.

The average weekly pay on the docks was only $10.45 a week. Yet competition even for these jobs was fierce during the Depression.

Strikes in 1919, 1924 and 1926 all failed – the owners overwhelmed each strike with company gangsters, police repression and scabs. Each time the bosses were able to break solidarity and divide the workers. Afraid of being banned from the docks, they soon returned to work. African-American dock workers, subject to Jim Crow discrimination and only allowed to work on two docks, were often forced to replace strikers on the docks.

There was a union, the International Longshoremens Association, but it was a company union and did not fight for the workers. Its leadership was weak and afraid of management, and did their bidding.

1930s brings new mood of fightback

But by the 1930s, however, new political winds were blowing. In 1933, despite 25 percent unemployment, nearly 1 million workers went on strike, in 1934 about 2 million.

The first sit-down strike, where workers not only struck but occupied the factory to win their demands, was in 1933 at the Hormel Packing Company in Minnesota. By 1936, there were 48 different sit-down strikes; in 1937 there were 477. In Detroit alone, workers sat down and refused to leave in every Chrysler factory, in 25 auto part plants, four hotels, nine lumberyards, 10 meat packing plants, 12 laundries and two department stores!

The new mood of the working class was also felt along the West Coast docks. A new union campaign began in 1933. It was led by Harry Bridges, an Australian-born immigrant, a seaman and dock worker, and an open communist. With the active support of the Communist Party, this militant grouping in the union began a bulletin, “The Waterfront Worker,” and filled it with phrases like “rank and file control,” “union democracy,” and explanations of “how racism hurts all workers.”

The organizers knew that to get a raise and better working conditions they had to end shape-up and for the union to control the hiring process. They strategized that there were two keys to the struggle: Rank and file control and anti-racist solidarity.

Outreach to Black community

Harry Bridges went to the Black community, to the churches and community centers and asked for a hearing. He encouraged the community to support the coming struggle, and he promised that there would be an end to discrimination on the docks and equality in hiring. He guaranteed that if the union controlled hiring, “if there were only two longshoremen left working on the docks, one would be Black and one would be white.” He proved to be as good as his word.

This was a big step forward for the union movement. Giving into pressure from bosses who maintained segregated workplaces, unions at these workplaces were segregated too. They did not strive to include Black workers. Thomas Fleming, the co-founder of San Francisco’s African American weekly, said this about his experiences on the docks: “Before 1934, I had the view that the trade union movement was just formed to continue racial discrimination. But Bridges asked for support, and promised that when the strike ended, African American workers would work on every dock on the West Coast …. When the ILA was recognized by the ship owners, African American workers got the same work as everyone else.”

Organizing the open shop

Many workers were not in the union, as this was an open shop, and union membership was not required. Union organizers learned not only how to talk, but more importantly, how to listen to the grievances of the workers on the docks, and slowly and quietly began to organize small groups of activists at each port. They were so successful that in six weeks the large majority of longshoremen had signed up with the union.

Despite the active hostility of the officials of the ILA, delegates from the newly formed rank-and-file committees called a convention of the International Longshoremen’s Association. Such was the strength of the organizing that the ILA officials were excluded from the convention. Times were changing!

A Joint Strike Committee was formed, demanding: 1.) A union-run hiring hall and an end to shape-up. 2.) A raise 3.) A coast-wide agreement. The demands also included an “equalization of work opportunities for all union members regardless of race or religion, protected work hours and improved safety conditions.”

The longshore strike began on May 9, 1934. Workers along the entire West Coast closed 2,000 miles of coastline. Teamsters refused to handle scab goods despite opposition from their own union president. Of 12,000 longshore workers on the West Coast, only 100 crossed picket lines during the 83-day strike. The company tried to get 1,000 scabs past the picket lines and into the docks, and each day was tense.

The ship owners and their corporate press attacked the strikers with lies and slanders. The press called the workers “rioters,” “looters,” “rats,” and even a “mob” that was “denying milk to hungry babies” in the same way that the the mass uprising against racism is slandered and attacked today. Police dressed like workers looted and beat up people and blamed it on the strikers. Despite death threats, bribery attempts and red-baiting, nothing could dent the union under the leadership of Harry Bridges, who insisted that, as president of the union, his salary would be the same as what the longshoremen received on the docks.

The spirit of solidarity was alive on the waterfront. A government agent, a specialist in hiring and arming company goons, was quoted as saying, “I’ve been able to break other strikes … but I can’t crack this one.”

The San Francisco general strike

When the workers rejected a secret agreement between owners and the ILA president, the owners tried to open the docks by force. Scabs, police and National Guard armed with machine guns and tanks prepared to break the strike. Thousands of National Guard were deployed to suppress the strike and escort trucks filled with scabs onto the docks.

The workers fought back. The result a pitched battle on July 5, 1934, now known as “Bloody Thursday.” According to the San Francisco Press:

“Police used their clubs freely and mounted officers rode into milling crowds. The strikers fought back, using fists, boards and bricks as weapons … strike pickets broke through the police lines and surged around a pile of bricks. Soon the air was filled with missiles … Police charged the crowd, but it did not move. The officers resorted to tear gas. Members of the mob, coughing and choking, picked up the smoking grenades and hurled them back into the police lines … police jammed tear gas guns against strikers, then pulled the triggers, blowing away the men’s flesh … police used the new ‘vomiting gas.’

“Meanwhile, the joint marine strike committee had sent out a plea to all unemployed members of every labor union to come down and join the picket lines, no matter whether they were on strike or not. The committee claimed several thousand answered the call.”

In the ensuing struggle, hundreds of workers were injured or arrested, and two killed — shot in the back.

Repression had the opposite effect than intended. San Francisco’s workers were outraged, and public support for the strikers swelled. The police chief banned people from attending the funeral of the two murdered workers. Yet the crowd there was so big that for 72 hours straight a double line of workers walked past the coffins of the two workers killed, and cops were nowhere to be seen. Some 40,000 workers and families came to the funeral march.

San Francisco is shut down

The following day 120 unions in the city voted for a general strike. Union workers were not the only ones who withheld their labor. Non-union truck drives stayed home. Movies and nightclubs, shops and restaurants closed, and the city shut down. Only emergency services continued. The strike lasted four days, but when the state threatened to declare martial law, the conservative leadership in the central labor council caved in, and called off the general strike.

The dock workers strike continued for another six weeks. Eventually, they were forced to accept arbitration and return to work. But this was very different from past strikes when the workers went back afraid and divided. When this strike ended, the workers on every dock simultaneously marched back onto the docks and went back to work as one. This solidarity enabled the union to win virtually every demand. For example, even though the contract arrived at through arbitration called for a “joint hiring hall” run by both the union and the company, the momentum of the struggle continued, and within a week after returning to work all hiring was done thru a union hall — a major victory.

Union hiring halls ensured that African American workers would be hired together with white workers. Anti-racist agitation among the white workers, and union-imposed penalties for racist behavior was the order of the day. It was this commitment to equality that built the solidarity needed to win benefits for all dock workers. This was a historic accomplishment during the depths of the Depression, when jobs were scarce and hardship was everywhere.

The union’s attitude to all the workers on both sides of the strike, including those who scabbed, was ground-breaking: To the white workers who didn’t support the strike and kept working, Bridges had this to say:

“You should be judged by what you do from here on. You didn’t understand, we weren’t able to get to you the right way. You weren’t the guys who came to break the strike, so straighten up and fly right.” Bridges fought to get the union membership to agree to this, and he said later of those who worked through the strike that “most of them turned out to be the best union men we ever had.”

To the company thugs and scabs from outside, there was no question that they would never work on the docks again.

Most African American workers supported the strike, but for those who did not and took jobs, Bridges supported them. He recognized the long years of Jim Crow shape-up and racist attitudes on the docks. He explained to the white workers, “Look fellas, the only way these guys ever got a job was because of the strike. No one can blame them for that. Let’s right now say: ‘you’ve got a job like a working stiff just like everyone else — no discrimination.’

In 1936 when the union was again forced to strike, there was solidarity all along the waterfront, and the owners did not try to import scabs or use violence against the strike.

The San Francisco general strike and dock workers victory in 1934 shows that solidarity in the struggle against racism is the way forward for the multinational working class. When working class organizers listen to the voices of the oppressed, listen to the voices of the workers, and from there chart the struggle, there is no obstacle too big to overcome. What once seemed impossible suddenly seems inevitable.