The author is an SWC member and is on strike.

On Nov. 3, the Student Workers of Columbia (SWC) went on strike for the second time this year. The union, which consists of graduate and undergraduate students employed by Columbia University in New York City, is one of the largest of its kind in the country at around 3,000 members. This makes it the second-largest currently ongoing strike in the United States, right behind the 10,000 John Deere workers now walking the picket line. The strike takes place amid an unprecedented wave of labor struggles across the country.

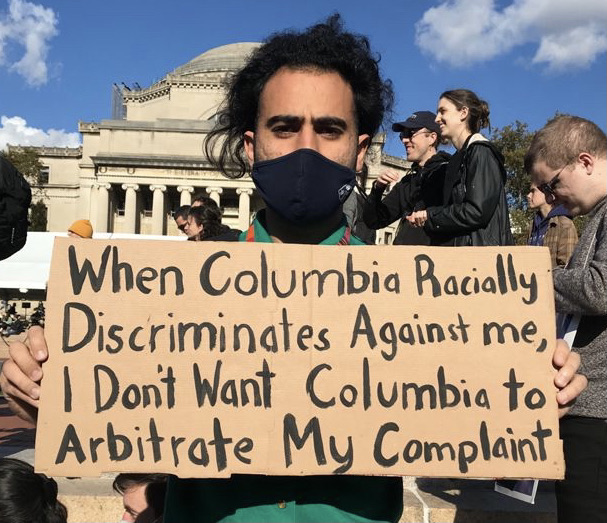

The Columbia strike kicked off its first day with a rally at the university’s Morningside campus with speeches by organizers and with hundreds in attendance.

The SWC is demanding higher pay, more comprehensive healthcare, and non-monetary benefits like neutral third-party arbitration in cases of discrimination and harassment. Despite Columbia being one of the wealthiest universities in the country with an endowment of $14.35 billion, the university still finds the SWC’s requests “unreasonable,” to quote anti-union lawyer Bernard Plum, who is representing the school in a recent bargaining session.

“Columbia’s assets appreciated by $3.3 billion between June of 2020 and June of 2021,” explained SWC organizer Charlie Steinman. “To look around and think, ‘Oh, our wages were frozen, there was no first year cohort [no new doctoral candidates] in the humanities departments and most of the social sciences.’ I’ve had it!”

Columbia joins other U.S. universities in a movement towards relentless austerity and endowment-growth, and pays its graduate students $9,000-$19,000 depending on the department, well below calculated cost of living for New York City. Many students end up having to leave the city in order to make rent, while others, particularly those with children or other financial dependents, have even had to go on SNAP benefits while working at an Ivy League institution.

“The university administration does not have our best interest in mind at all,” argued SWC member Jehbreal Jackson. “They’re making decisions that are clearly punitive — that make our lives of trying to learn harder, so that we can’t afford rent and we can’t afford childcare — a whole list of things!”

At the end of a nearly month-long strike last spring, the SWC and Columbia reached a tentative agreement that was ultimately voted down by the union body, citing “unimpressive and unsubstantial” raises and healthcare funding, as well as the fact that the agreement lacked neutral third-party arbitration for discrimination and harassment cases brought against the university.

This is a particular sticking point for Columbia, which refuses to give up complete jurisdiction over its employees in cases of sexual harassment, a situation which union organizers claim has allowed Columbia to shield prominent non-student employees from harassment charges.

This time, however, organizers were confident that the strike would be able to push bargaining further. Firstly, the university isn’t offering remote-only classes, meaning that students (including strikers) are on campus.

Undergraduate students have been particularly important in the effort thus far. Many undergraduates themselves are striking with the union, and others have organized solidarity actions — perhaps the largest of which is food distribution to the picket line.

Udonne Eke-Okoro, an undergraduate distributing food to strikers, said he was motivated to do so by “what happened in 2020 with people not getting paid” and by “just seeing people struggle, and me viscerally seeing that struggle. It’s something that’s affecting my educators, and that’s something I need to go and change.”

Perhaps just as importantly, administrators are no longer able to work from home, exposing top-level personnel like University President Lee Bollinger to militant actions, like this classroom protest that occurred Oct. 27 during a pre-strike demonstration. Currently there is no end date to the strike, and little progress has been made at the bargaining table in the first few days.

Despite all this, morale on the picket line is high, and organizers showed little sign of stopping before a good contract is reached.

“This university can afford to treat us better,” Steinman said. “And even if it couldn’t, we’re human beings, and we deserve it.”