Millions of women in Mexico went on a historic, nationwide strike on March 9, boycotting workplaces and other spaces, like schools and marketplaces, to protest gender-based violence and the government’s impunity in face of the country’s surging femicide rate.

Workplaces and public spaces−parks, libraries, and public transport−were nearly empty with only men present because women joined the 24-hour protest, called “Un Día Sin Mujeres” or “A Day Without Women”. It is the largest women’s strike in the history of Mexico, whose past is rich with mass labor and student strikes.

The mass protest was organized to demonstrate how the absence of women impacts society. In an interview with the Guardian, Sandra Reyes a biologist at the National Cancer Institute, who participated stated, “In some ways, it’s a taunt: if you do not want us out here in the streets, we’ll disappear.”

80,000 march in Mexico City

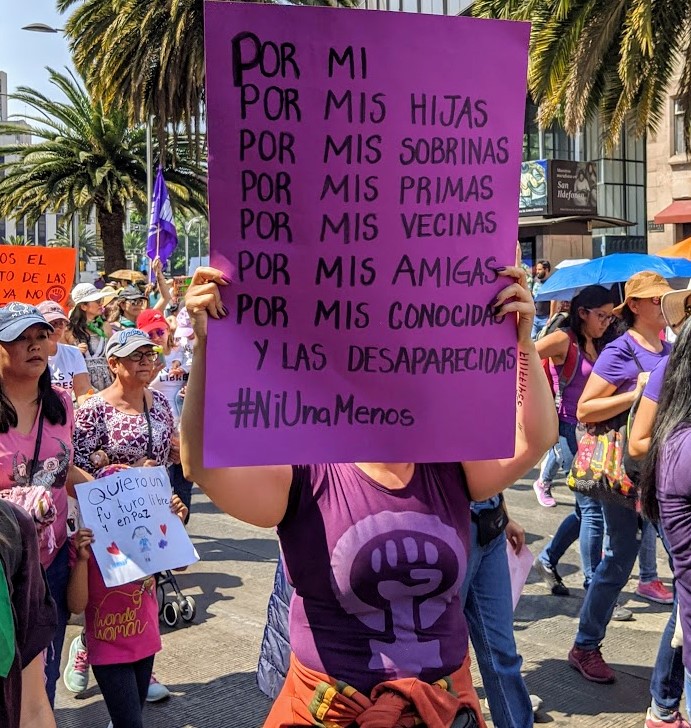

The 24-hour anti-femicide strike followed a series of protests nationwide March 8 to mark International Women’s Day and to demand justice for victims of femicide. The march in Mexico City was at least 80,000 strong, making it the largest such action in Mexico’s history. Women in every age group and from every walk of life participated. Mothers brought their daughters. Indigenous women marched. In the crowd were family members of those who had been killed and disappeared.

Femicide an international issue

A huge demonstration and general strike also took place in Chile March 8 and 9, with women raising related issues. Killing of women, usually by intimate partners, is being called a global pandemic. In the U.S., for example, three women are killed every day, mostly by intimate partners, and trans women are murdered at even higher rates.

Protests follow a spate of femicides in Mexico

In Mexico, the watershed moment of major protests and a strike was triggered by an upsurge of fury and outrage over the grisly murders of a young woman and a seven-year-old girl in February, the latest in a spate of gender-based murders.

The woman, 25-year-old Ingrid Escamilla, was stabbed, skinned and disemboweled, and the girl, 7-year-old Fátima Cecilia Aldrighett, was kidnapped from school; her body was later found wrapped in a plastic bag.

Media sensationalizes the deaths

Gruesome photos of the mutilated body of Escamilla were leaked to the press and published on the front pages of tabloids, provoking even more outrage and anger.

Pasala, one of the tabloids, published the photo with the headline “It was Cupid’s fault” − implying that the murder was an act of love instead of an act of brutal misogyny.

Subsequently, leaked photographs and videos showed a bloodied man who apparently confessed to stabbing Escamilla after what he claimed was a heated confrontation, before reportedly skinning her to destroy evidence.

“The distribution of images of criminal acts, as a form of advocating crime involving sensationalism, viciousness, mockery, and morbidity, causes revictimization, banalizes violence, and threatens the dignity, privacy, and identity of victims and their families,” the National Institute of Women stated.

Other deaths demonstrate not only the global pandemic of violence against women, but also the attack on women activists. In January, Isabel Cabanillas de la Torre, a Mexican anti-femicide activist and artist, was murdered in Juarez.

Following these and other killings, on February 14, scores of activists, many wearing green handkerchiefs symbolic of women’s rights, gathered outside Mexico’s presidential palace to protest violence against women. The women protestors were chanting “Not one more murder” and sprinkling blood-red paint on one of the massive, ornate doors and the words “femicide state.”

Violence against women is so widespread, that nearly two-thirds of girls and women have reported experiencing violence at some point in their lives. In recent years the incidence of femicides in Mexico has escalated. In 2019, 1,006 such killings were reported by Mexican authorities, a 10 per cent jump over the previous year. This means that in 2019 there were 10 women killed per day. In February, Mexico’s attorney general said femicides have risen an unprecedented 137 percent over the last five years, four times higher than the general homicide rate.

Since few cases are ever prosecuted and punished, the number of femicides is possibly higher. Experts at the University of San Diego said the majority of femicide murders are being handled with “systemic immunity.” Too often, the justice system remains unresponsive. Reports state that 98 % of cases go unpunished.

Protests target president’s inaction

Many feminist activists and collectives have criticized President Andrés Manuel López Obrador for being dismissive and condescending in his responses to the protests.

In early February, Obrador said at a press conference “Look, I don’t want the topic to be only femicide,” he said. “This issue has been manipulated a lot in the media.” He sought to dismiss the femicide crisis on what he called the “neoliberal policies” of his predecessors. Neoliberal policies do hurt women, but many feel that Obrador is using this to shield himself from criticism about his inaction.

In face of the pandemic, Obrador has put no policies or referendums, or any measures of any kind in place to protect women from sprawling sexist violence. Instead, Obrador has buckled-down and stated at one of his daily news conferences that he will not make changes to governmental policy on gender-based violence and that he will not give into the demands of feminist protesters.

“The message he’s sending women is I don’t care,” said Maricruz Ocampo in an interview with the Guardian, an activist in the state of Querétaro. “They’ve all had the same attitude toward the problem,” she said. “This is a Mexican problem, not a women’s issue.”

The strike demonstrates the labor power of the women workforce. If all women participated in the strike, the action could cost the economy up to $1.37 billion. According to Mexico’s National Chambers of Commerce Confederation, women make up around 40 per cent of the country’s workforce.

U.S. neoliberal policies leave Mexican women vulnerable

Mexico’s skyrocketing number of femicides and gender-based violence cases have a direct correlation to neoliberalism and the patriarchy.

The United States has imposed a free trade agreement on Mexico that is gutting the Mexican economy while enriching the U.S. capitalist class.

Under the neoliberal model, women are vulnerable, especially poor and indigenous women, to exploitation and violence. It is common for women to travel from their rural Mexican colonias, where unemployment is high and industries scarce, to work at maquilas, American-owned transnational factories, at the border.

Hundreds of femicide victims in Mexico, especially near the borders, were in fact factory workers. Often, the women employed at these factories are subjugated to extremely low wages−on average $5 a day−and excruciatingly long hours.

To transnational companies, the safety and welfare of women workers are of little concern. Commonly, the women working in the maquilas, must commute by foot at night in remote city areas.

In one case from 2001, 20-year old Claudia Ivette González was found brutally murdered in Juarez a day after she was forced to walk home from the maquiladora she worked at after being fired. González was fired for being a mere four-minutes late for work!

#ADayWithoutWomen comes amid a global upsurge of women fighting back in the streets, organizing and building movements that are exposing the world pandemic of gender-based violence and sexual assault. Across Latin America alone, a record-breaking 8 million women marched on International Women’s Day. Protesters across the globe performed en masse “A Rapist in your Path” −a Chilean protest song that denounces misogynistic and political repression.

There is an international struggle going on right now to eradicate misogynistic violence and to demand that justice prevails. Millions of women around the world have taken up this call and will not back down until victory is achieved!