One by one the injustices of life under capitalism weigh all of us down each and every day: rent increases, long work days, the rising costs of living, the struggle to enjoy our lives in peace and security, and so on. From their perches of property and privilege, the landlords, bankers, politicians, and bosses who shape our lives and appropriate the social wealth we create look down on the rest of us with little concern. This usually inspires anger, fatigue, and feelings of powerlessness. Indeed, that’s the purpose of the innumerable oppressions that make up the backbone of everyday life under capitalism: they are intended to wear us down and break through that fighting, social spirit which is characteristic of being human. They are meant to make us give up.

One by one the injustices of life under capitalism weigh all of us down each and every day: rent increases, long work days, the rising costs of living, the struggle to enjoy our lives in peace and security, and so on. From their perches of property and privilege, the landlords, bankers, politicians, and bosses who shape our lives and appropriate the social wealth we create look down on the rest of us with little concern. This usually inspires anger, fatigue, and feelings of powerlessness. Indeed, that’s the purpose of the innumerable oppressions that make up the backbone of everyday life under capitalism: they are intended to wear us down and break through that fighting, social spirit which is characteristic of being human. They are meant to make us give up.

The opposite, however, has been the case at three adjacent apartments owned by one company on Burlington Avenue in Westlake, Los Angeles, where, faced with the potential eviction of nearly a hundred families (making up more than 300 people, mostly immigrants, low wage workers, and their families), residents have fought oppression with unity by launching a massive rent strike.

Organizing first independently under the banner of Burlington Unidos, then with the help of the VyBe chapter of the Los Angeles Tenants’ Union, the tenants at the apartment complexes have been using direct action to assert and defend their rights. Eighty-five out of 192 units have been refusing to pay rent since March, causing a serious loss of more than $100,000 a month in the landlord’s profits. Working in conjunction with similar actions going on in other parts of Los Angeles County, including Boyle Heights and University Park, they are expressing a form of collective power that no amount of pressuring ‘elected’ officials or using channels of discontent acceptable to those in power would have been able to achieve.

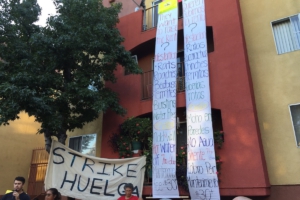

The tenants’ demands are simple. They want their concerns listened to, an end to abuse from management, and any rent increases to be reasonable and democratically agreed upon. While the buildings’ owner, Lisa Ehrlich, and her children live in West Los Angeles in million dollar homes, the residents are facing a long list of daily injustices (displayed in Spanish and English on a long banner draping across the building’s facade) that include rats, cockroaches, bedbugs, termites, bursting water pipes, a broken elevator, mold on the walls, hot water outages for seven hours a day and $30 maintenance fees. While responding to none of these problems, Ehrlich announced rent increases ranging from 25 percent to 50 percent of tenants’ current rates. She has refused to meet with residents who have reported abuses and retributions for speaking out.

On July 20, Burlington residents held a rally with support from multiple L.A. Tenants’ Union chapters, Democratic Socialists of America, She Does Movement, ANSWER Coalition, and others. Despite the great and overwhelming injustice of the situation, and the arrogance of the owners on the other side of the conflict, the mood of the evening was optimistic and charged with energy; a march around the block was led by young children living in the buildings, who gave speeches and talked of how the situation has caused them to fight for their community and realize the power of collective struggle. A young resident, Briana, said that “this is showing everybody that we can fight for want we want as a community.” Protesters had gone earlier to Ehrlich’s home neighborhood of Pacific Palisades handing out flyers explaining how one of their community members was evicting dozens of young immigrant children from a building she owned via inheritance. Outside the buildings, tenants had lined Burlington Avenue with a small tent city called “Ehrlichville” to highlight the real consequences the owner’s mass eviction would have. These actions spoke to a general feeling of militant struggle to defend housing rights.

A Burlington Unidos organizer spoke about how he had heard from families who had been looking to move to locations as far away as Las Vegas, unable to afford anywhere else in a rapidly gentrifying Los Angeles. “We are being evicted every day,” he said, pointing out that 50 children from the building attend the elementary school across the street; other residents have relatives who access the dialysis center within walking distance. Elena Popp, the housing rights lawyer fighting the striking tenants’ cases said that “Los Angeles is quickly turning into another Laguna Beach,” where Latinx immigrants come in to do the hard, underpaid work that keeps society running for the rich, while being forced to live far away. She Does organizer Mel Tillerkeratne called it “a war on the poor.”

Popp explained how L.A.’s lack of effective rent control measures (the 1995 Costa-Hawkins Amendment, pushed through after lobbying from landlords and developers, means that rent control laws do not cover buildings built after 1980) makes these increases “unjust, but legal.” With many residents at the apartments already spending a large portion of their paycheck on rent, the hikes would push the majority out of the neighborhood and likely the city. So far, she has won five of the eviction cases in court, losing three. Since all of the families on rent strike are entitled to a trial, she said she is confident that continuing the action will bear fruit and push Ehrlich to negotiate.

The last few months, while driven by these dire circumstances, have shown that struggles against the abuses of landlords can draw mass attention, inspire many, and build confidence in the strength of collective power when radical uncompromising tactics are taken as in Westlake. An anonymous LATU member called the rent strike “a symbol of a wave spreading across the nation,” and this can only be a good thing.