The following article appeared Dec. 1 on pslweb.org.

Working-class and oppressed people are not likely to mourn the death on Nov. 16 of Milton Friedman (1912-2006). He is acclaimed by the bourgeois media as a brilliant Nobel Prize-winning economist who explained how free markets and free trade, privatization of public services and unrestrained pursuit of capitalist profit can raise living standards to the maximum extent possible.

Friedman in reality was among the most vulgar of bourgeois economists promoting policies—often referred to as “neoliberalism”—that reinforced objective trends within world capitalism that have increased poverty, squeezed the middle class and widened the gap between rich and poor.

Milton Friedman was an originator of the “Chicago school” of economics in the 1950s. This is a school of thought favoring “free-market economics” and extreme anti-labor policies that was promoted by a group of economists at the University of Chicago, where Friedman taught for many years.

Friedman made his mark as an ideologue arguing for non-interference in the capitalist economy. He published many papers, articles and books and, in later years, frequently appeared on television. He also advised governments.

According to the Library of Economics and Liberty website, Friedman in his work ”Capitalism and Freedom,” “liberated the study of market economics from its ivory tower and brought it down to earth.” This refers to Friedman’s knack for popularizing the “neoclassical marginalist” school of bourgeois economics.

Pro-capitalist university professors developed this school in the last third of the 19th century to counteract the growing influence of Marxist ideas in the rising European workers’ movement. Marx, together with Frederick Engels, had put socialist ideas on a scientific footing by further developing the valid findings of the early bourgeois “classical” economists.

Ideological rather than scientific, neoclassical marginalism held that a capitalist economy would always tend toward full employment in the absence of trade unions, pro-labor government legislation or other similar interferences with the “free market.”

Great Depression shakes up bourgeois ‘theory’

The Great Depression of the 1930s, with its massive unemployment, blew this theory out of the water. As the depression dragged on, a workers’ radicalization brought about the stormy rise of industrial unions and the militant Congress of Industrial Organizations in the United States. This working-class upsurge, along with the powerful example of the first five-year plans in the Soviet Union, forced the capitalist ruling class to grant major concessions.

These included a retreat in the realm of bourgeois ideology that was led by the British economist John Maynard Keynes. Early in his career, Keynes had also been an adherent of neoclassical marginalism. In the 1920s, he partially broke ranks by advocating deficit-financed public works to alleviate post-World War I unemployment in Britain.

He did this as a supporter of the bourgeois Liberal Party to counter the rising Labor Party, which had not yet developed such a program. In response to the 1930s crisis, Keynes again advocated public works and other government measures to reduce unemployment. Later in the decade, Keynes and his supporters carried out a major revision of neoclassical marginalist theory: They admitted that the capitalist economy was basically unstable.

Far from keeping its hands off the economy, according to this new view, the government should actively intervene to keep unemployment from getting completely out of hand. Keynes advocated these policies for fear that otherwise the working class might overthrow the capitalist system of exploitation, to which he remained loyal.

The concessions granted to the workers’ movement in the United States, and the incorporation of that movement in the “New Deal” Democratic Party, staved off the threat of revolution. The long period of relative capitalist prosperity that followed World War II allowed the labor movement to further expand within the framework of U.S. capitalism. Additional concessions were wrested from the ruling class by labor and by the civil rights and other progressive struggles that arose in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s. For some partisans of progressive social change, Keynesian policies appeared to be working.

Capitalist counteroffensive

The anti-Soviet Cold War initiated at the end of World War II was accompanied by purges of communists and socialists from the labor movement and movie industry, expanding into a veritable witch-hunt. The capitalist rulers were bent on carrying out a counteroffensive. This extended to the ideological front.

This is where Milton Friedman “rose to the occasion.” He sought to restore the anti-labor doctrines of neoclassical marginalism to their former unchallenged dominance.

To have any hope of success, however, Friedman had to explain—or, rather, explain away—the Great Depression. He developed for this purpose his “monetarist” theory.

Friedman claimed that it was the overly restrictive policies of the Federal Reserve System, the U.S. central bank—and not the basic instability of the capitalist system, as the Keynesians maintained—that caused the depression. To “prove” this, Friedman slightly modified the old quantity theory of money, a doctrine that had been a centerpiece of bourgeois political economy even before neoclassical marginalism made its appearance. Friedman put forward these views in his “Studies in the Quantity Theory of Money,” published in 1956.

Friedman and co-author Anna Schwartz in their 1963 “Monetary History of the United States, 1867-1960” claimed that previous overproduction crises and periods of inflation and deflation covered in their study were correlated with, and therefore caused by, fluctuations in the money supply. Friedman even argued that future capitalist economic crises, though not minor fluctuations in the economy, could be eliminated if only the Federal Reserve were required to increase the money supply at the same rate as the estimated growth of real economic output.

Karl Marx devoted his 1859 book, “A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy,” and large sections of “Capital” to refuting the quantity theory of money. In recent years, Friedman’s monetarism has fallen out of favor, even among pro-capitalist economics professors, owing to the failure of monetarist economic predictions and the practical impossibility of bringing about a steady growth of the money supply.

Despite Friedman’s efforts, Keynesianism retained its influence among bourgeois economists and politicians for a number of years. Even Richard Nixon famously said, when he imposed wage and price controls in 1971, “We are all Keynesians now.”

Dollar crisis and ‘stagflation’

Then came the severe overproduction crisis of 1973 to 1975, which had been preceded by a crisis of the dollar. “Stagflation” made its appearance. This refers to a period marked by sharply declining currency values against gold, rapidly rising prices in terms of the depreciating currency and stagnating production and employment such as occurred in the 1970s.

Nixon’s wage and price controls failed to prevent further weakening of the dollar. In 1972, the gold-dollar standard for regulating world trade and finance established at a July 1944 international conference held in Bretton Woods, N.H. was formally abandoned.

Keynesian fine-tuning could not prevent the severe overproduction crisis that began in 1973. A weak recovery followed, but then stagnation set in, during which the Carter administration administered the prescribed Keynesian stimulant of deficit spending.

The Federal Reserve head in 1978 and 1979 was G. William Miller, whose background as an industrial capitalist—he had been the CEO of Textron, Inc.—contrasted with the usual banker or finance capitalist credentials for this position. Miller accommodated the Carter administration with an easy-money policy. Once again, the dollar dived in value against gold, and inflation took off. Long-term interest rates rose sharply as money capitalists insisted on an “inflation premium” to compensate for the risk of further dollar depreciation.

As the 1970s unfolded, bourgeois economists and politicians became increasingly disillusioned with Keynesian policies, and Milton Friedman’s star began to rise. Friedman claimed that government meddling in the economy had again produced a major crisis, except in this case too-loose monetary policy had brought it about, in the form of stagflation.

Friedman and Volcker to the rescue

In August 1979, Paul Volcker, who was close to the Rockefeller family and had impeccable banker credentials, replaced the hapless Miller. Under the cover of Friedman’s monetarism, Volcker announced that the Federal Reserve was abandoning its traditional policy of targeting short-term interest rates in favor of targeting the money supply. Actually, as he revealed in his 1992 book “Changing Fortunes,” Volcker understood that interest rates had to rise dramatically to stabilize the dollar, whatever the effect on the money supply.

The resulting impact on the financial markets, known as “the Volcker shock,” was dramatic. Short-term interest rates shot up to historic highs, the money supply contracted and the dollar stabilized.

Over the following two decades, there were three crises of overproduction: from 1980 to 1982, from 1990 to 1991 and from 2000 to 2001. The capitalist business cycle had by no means been eliminated.

The Great Depression in the 1930s had also negatively impacted U.S. industry. But thanks to the exceptionally low interest rates prevailing during that period and even during the war years that followed, industrial production recovered and then began a long and robust expansion. In addition to the low interest rates, elimination of excess and obsolete productive capacity in the course of the depression and during the war laid the basis for the long period of relative capitalist prosperity that followed. The surge in military spending for World War II provided the catalyst.

Industrial decline and ‘financialization’

The 1980s and 1990s saw a decline of U.S. industry that included permanent shutdowns of large sectors of U.S. heavy industry (creating the “rust belt”), the closing of other factories and transfer of production to developing countries where wage costs were lower and the downsizing of loss-making industrial operations of corporate giants such as GM and Ford in favor of gigantic consumer lending operations that soon began generating the bulk of these companies’ profits.

According to Kevin Phillips in his 2006 book “American Theocracy,” the percentage share of U.S. corporate profits from manufacturing declined from 23.8 percent in 1970 to 12.7 percent in 2003, while profits from financial services rose from 14.0 percent to 20.4 percent over the same period. He calls this the “financialization” of the U.S. economy.

The decline of heavy industry and manufacturing in the United States was a very negative development for the U.S. labor movement, whose backbone industrial unions were thrown on the defensive and declined precipitously in members and clout.

It was in this context that capitalist governments worldwide—led by the Reagan administration in the United States and Margaret Thatcher in Britain—began aggressively to push neoliberalism, for which Milton Friedman provided ideological talking points.

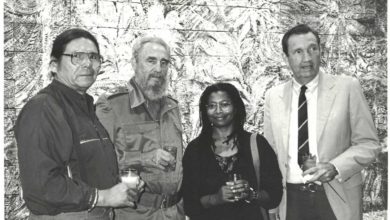

Partly a consequence of and partly reinforcing the reactionary worldwide neoliberal trend was the demise of the socialist camp, including the Soviet Union, in the period from 1989 to 1991. This had been the stated goal of the anti-working-class counteroffensive launched by the capitalist rulers at the end of World War II. What Fidel Castro characterized as the greatest working-class defeat in history, demoralized and disoriented most of the worldwide left. In combination with the decline of the industrial unions, this defeat led to the disintegration of many workers’ parties and sharp moves to the right by others. Socialism appeared to have failed in practice.

Economic crisis and socialist renewal

The recovery from the most recent period of overproduction crisis and stagnation (2003 to the present) has been anything but robust. Many commentators have termed it a “jobless recovery.” Interest rates fell to the lowest levels in many years as industrial production hit bottom, but recovery of U.S. manufacturing has been unimpressive. The main beneficiary of the low interest rates was the construction industry after a housing bubble replaced the pricked stock market bubble of the 1990s. Now with interest rates on the rise, this bubble is deflating and threatens to burst.

There can be little doubt that the U.S. and world economies are headed for another period of major economic crisis. Experience has shown that neither Keynesian prescriptions nor Friedmanite nostrums can prevent it—though government and central bank policies will certainly shape its outcome.

The main unanswered question, then—other than the timing, which is impossible to predict with precision—is what form the coming crisis will take: Will it be a deflationary crisis of overproduction followed by an extended period of depression and stagnation like the 1930s? Or will the dollar crash bringing about another period of stagflation like the 1970s, or perhaps a hyperinflation?

In recent years, movements have arisen in the United States that have mobilized millions in mass actions against imperialist war and in defense of immigrant rights. Labor struggles involving the most oppressed and exploited sectors of the working class, including hotel workers, janitors, meatpacking and healthcare workers, farmworkers and day laborers have scored modest but significant victories.

Popular movements in Latin America have arisen that are challenging and in some instances overturning the policies of neoliberalism promoted by Milton Friedman. Militant workers’ struggles in Korea are showing the way forward in that part of the world.

Revolutionary-minded leaders and activists of these struggles are growing in numbers, expanding their influence, reaching out to one another across movement and national boundaries, and giving impetus to a renewal of the worldwide movement for socialism.

These and other progressive developments, along with the continuing scourge of imperialist war, provide the context within which the coming economic crisis will unfold. Whatever form that crisis takes, it is safe to say that it will open the way for revolutionary movements that can, down the road, eliminate imperialist wars, economic crises and the gross inequalities of capitalism—and bury the neoliberal legacy of Milton Friedman, permanently.

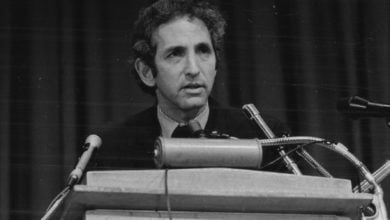

Milton Friedman, bourgeois ideologue and enemy of the working class

Photo: Mark Richards

Unemployed workers during the Great Depression

Photo: Zuma Press

Friedman met with Pinochet in Chile in 1975, two years after the bloody coup.

Photo: Files Reuters

Immigrant rights march, San Francisco, May 1

Photo: Michelle Gutierrez