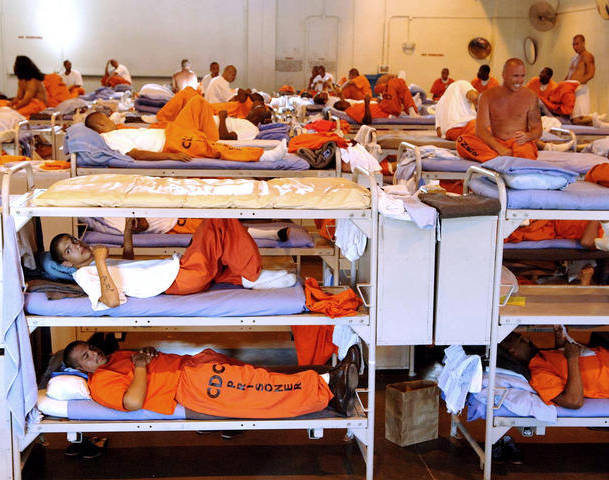

The United States Sentencing Commission has again made a major decision taking a step back from some of the more draconian drug policies at the federal level. The roughly 2 million people behind bars, 7 million including those on parole or probation, has become one of the most embarrassing aspects of the American social landscape. The “justice” system from top to bottom is constantly in the news for everything from police brutality and draconian sentences to deplorable prison conditions. The scale of abuses consistently makes a mockery of the democratic rhetoric that flows from official institutions and individuals.

As such, the U.S. government is taking steps to—in appearance at least—clean up their act. In April, the Sentencing Commission voted to loosen sentencing guidelines on convictions regarding possession and distribution of drugs. To be exact, it lowered the importance of the quantity of drugs vis-à-vis other factors when determining a sentence. Theoretically, this should reduce sentences for drug crimes and give judges more latitude in sentencing.

While this was a limited victory, it was welcome. It is clear that the significant advocacy opposing mass incarceration is starting to have an echo in policy discussions. The biggest criticism raised by many of us who have pushed for years for serious changes to the criminal “justice” system was that the changes would not be retroactive.

Now the USSC has moved to address that as well, declaring that they would make their new guidelines retroactive. This will give about half of all federal drug prisoners the chance to apply for a reduced sentence, with an average reduction of roughly two years.

So the real question is what does this all mean?

This ruling is not entirely, but largely, symbolic. Most of the country’s prisoners are doing state time and most states continue to mete out extremely harsh sentences for drug crimes, even of the non-violent type. Overall, just about 3 percent of those locked behind bars will be affected under the new guidelines. Further, because of the constraints the USSC works under, the new guidelines still cannot reduce sentences to below the mandatory minimum for that crime.

For more to happen, Congress and the president would have to intervene. The prospects for this are mixed. It is clear there is a growing cohort of congressional officials, plus Eric Holder and President Obama, who are critical of at least aspects of the war on drugs, sentencing in particular.

The reality is that the “War on Drugs” isn’t just about drugs. The War on Drugs is more or less a response of the capitalist elites to social deprivation in the ghetto. Rather than solve the immense crises caused by the shifting sands of the economy, they decided to ring-fence it. Rather than deal with the conditions that created the black market in drugs (and an interconnected and flourishing black market in a number of goods) it decided to simply control them. More and more militarized cops, more and more brutal prisons, longer and more punitive sentences with less “rehabilitation.” Mass Incarceration is a method of social control connected to the particular interplay between the economic and the social in the neoliberal period. These conditions are deeply entrenched in neighborhoods around the country. Poverty, unemployment and so on are not just going away.

So what to do? Massive jobs program? Not on the table. Free college education for poor youth? They won’t even give jobs to actual college graduates.

Thus, moving away from mass incarceration requires more than just moral outrage in the general sense. It has to answer a whole range of questions that have been given answers by the “lock-em-all-up crew.”

What is crime and how to prevent it? Should all drugs be legal or just some? How do you punish rapes and assaults? When do we know if people have been rehabilitated? More fundamentally, what are the root causes and can we ever eliminate crime? These questions speak to holistic answers, moving from a social system in which competition and profit trump all else to one that prioritizes people’s needs.

Needless to say, building a socialist society is not something capitalist politicians want to discuss, so figuring out how to both curb mass incarceration while neutralizing those who prefer this system of social control often falters on the political shoals when capitalist reformers have few or no answers to the questions above.

So clearly taking aim at reforms of the so-called criminal justice system can be effective, and is having an effect. However dismantling mass incarceration requires we go much further, and start to dig in at the roots that are capitalism and its assorted maladies.