This article was originally posted in 2011. We are reposting it in celebration of Black History Month.

“Lead the Negro to believe this [that he is inferior] and thus control his thinking. If you can thereby determine what he will think, you will not have to worry about what he will do. You will not have to tell him to go to the back door. He will go without being told; and if there is no back door, he will have one cut for his special benefit.” Carter G. Woodson (1933)

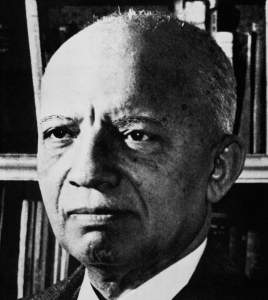

Carter G. Woodson was a man who understood that controlling the history and education of an oppressed people is essential to maintaining their oppression. Woodson was an educator, a historian and the founder of the Association for the Study of Negro History and Life as well as the founder of Negro History Week in 1926.

Negro History Week was intended to be a weeklong celebration of the rich history and achievements of people of African descent in the U.S. In 1976, that week became Black History Month, and now it is observed every February in the media, in schools and in communities across the U.S.

Black History Month is meant to combat the ideology of white supremacy that is prevalent throughout much of the popular understanding of U.S. history and pop culture. In order to reinforce the idea that African Americans are inferior and thus incapable of contributing much to society, the historical contributions made by African Americans are minimized or excluded altogether in the official narrative.

This denial of the role of Black people in U.S. history is one part of the overall strategy used by the ruling class to continue the oppression and exploitation of Black people. So the creation of a Negro History Week, in which Black contributions were exclusively highlighted, was a significant step forward in the struggle for Black equality in the official history of the United States and in society as a whole.

Woodson believed in the importance of using examples from history to instill pride in Black Americans and to force whites to accept the integral role played by people of African descent in the overall history of this nation.

Woodson lived under conditions of Jim Crow segregation in the South in the first half of the 20th century. In the time and place in which he lived, the very humanity of African Americans was in question, with legislators refusing even to act against lynching, for example. The denial of basic rights for the Black population was the law of the land.

But this period also saw the emergence of a robust and committed African American intelligentsia that used history and literature as their weapons of choice in the fight for Black equality and liberation.

Although this intelligentsia came from many classes, the advancement of the entire community was their goal. Many of them railed against poverty and exploitation by name, and many were members of the Communist Party USA at some point in their lives.

This charge on the cultural front was lead by prolific writers and historians including Woodson and W.E.B .DuBois, and was joined by writers Paul Lawrence Dunbar, Claude McKay, Zora Neale Hurston, Langston Hughes and countless others. Their work comprises a historical and cultural polemic against the idea of the inferiority of African Americans and had an explosive impact throughout Black communities and society at the time. Sadly, it may only be during Black History Month that many school children learn about their legacy today.

Historian John Hope Franklin was a colleague of Woodson and a critic of Black History Month in modern times. Of Woodson, he wrote, “In succeeding years, down to his death in 1950, he continued to express hope that Negro History Week would outlive its usefulness.” Woodson clearly wanted to overcome the marginalization of Black history in part through the mechanism of the Black History Week or Month.

Franklin expressed the view held by many present-day African Americans that Black History Month has become a commercialized and empty gesture, or a form of tokenism, that allows Black history to continue to be marginalized and ignored for the other 11 months of the year. Franklin, who is now deceased, famously used to refuse any invitations to give lectures about Black history during the month of February.

On the other side of this debate, scholar Allen B. Ballard, who attended a segregated elementary school in Philadelphia in 1930, explained what Negro History Week meant to him and his classmates. He wrote that, after Negro History Week “… we really knew that we were important people, that great things were expected of us, and that we had a tradition of honor, excellence and perseverance to uphold. That meant a lot to us as we daily walked by the spanking brand-new white school with its high wire fences on our way to the Hill school three blocks past it.”

Ballard’s position is clear, stating, “If anything, the need for such a program is even more evident today than it was in my childhood.”

Until the racist ideology of the ruling class is no longer the dominant ideology, Black History Month will continue to be an important opportunity to instill knowledge and pride in African Americans and to educate and overcome the racist ideas or distorted understanding of Black history that may remain among white workers.

Black History Month challenges a system that asserts a version of history where every great deed was done by rich white males. According to this history, women, poor people, and not only Black but all people of color, have played no significant role and occupy a secondary place in society. The Party for Socialism and Liberation is proud to participate in Black History Month through forums and articles, though stories of the triumphs and achievements of working-class people of all nationalities can be found in our publications every month of the year.