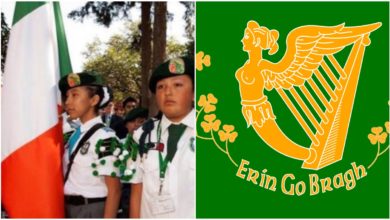

“Free trade” has meant vast profits for multi-nationals and poverty for millions in the southern hemisphere. Photo: Bill Hackwell |

In the 1990s, the resistance of the social movements was against the neoliberal model associated with “structural adjustment” plans put out by the International Monetary Fund, warmly supported by the World Bank.

We are currently going through the “wave of free trade” that has gone far beyond the traditional meaning of the term “free trade.” Today, it means not only or even not so much trade. Rather, it means the global projection of a strategy of imperialist domination that uses neoliberalism as its mode of being, but which branches off and extends, turning into a truly integrated package.

Today, when we hear the term free trade from the lips of the U.S. government, the G-7, the IMF, or the World Bank, it means much more than trade. It includes the FTAA and WTO negotiations; the Bilateral and Multilateral Treaties of Free Trade and Investments; the regional accords like Plan Puebla Panama, the Andean Accord on trade and drug eradication; the plans for militarization and repression like Plan Colombia, the installation of military bases and the foreign debt.

For the neoliberal paradigm that is heatedly defended by the IMF, the World Bank and the G-7 governments, the problem is very simple and clear: the greater the liberalization of trade, the greater the economy grows. Poverty is reduced and there is general progress.

According to this view, the market functions perfectly if trade is genuinely free: there will be better assignments of resources, and the optimal specialization will be established for each country. So that the market functions perfectly, nothing must upset the free action of the market. The state must keep its hands off trade and the economy in general so that the market and the comparative advantages that it determines will be resolved in the best possible way.

It’s just the old liberal theory submitted by Adam Smith’s “Wealth of Nations” in 1776, now dressed up with econometric models and sophisticated rhetoric, but still with all the deficiencies it has had since its origin and has been unable to erase. These deficiencies include: comparative advantages statically conceived, so that the free market depends on them and makes them eternal; it presumes a static combination of resources and factors in a world of small enterprises of relatively similar scale, in which no one company would have decisive advantages over the others in terms of information, finance or technology.

It is a world without transnational companies, with an international trade almost exclusively in goods-without monopolies of intellectual property, without inter-firm trade or massive corporate chains controlling within their orbit everything from the sowing of coffee seeds to the final commercialization.

It is a world without the determinate realities of contemporary capitalism. For that reason, it is incapable of explaining what is happening, although neoliberals always invoke it as the supreme root of economic science.

It is impossible to forget that Smith’s theory of free trade granted the United States growing prosperity based on its agriculture. The U.S. should ignore industrial manufacturing and take advantage of its agriculture while it imports British manufactured goods. But U.S. governmental figures like Abraham Lincoln did everything to the contrary.

Considering the Bush administration’s free trade rhetoric today, they would have been labeled horrible protectionists by Smith because they used the government to play an active role in modifying the comparative static advantage. They also created other advantages that made the U.S. abandon its role as an agricultural country.

History has not been kind to the liberal theory of international trade. But curiously, Smith, the economist presented as the intellectual paragon of free trade theory, was less radical in his free-market faith than Bush, as his speeches on the benefits of the FTAA and other free trade treaties reveal.

Adam Smith’s words would be very unsatisfying to the U.S. Department of Trade, to the IMF, to the World Bank and to the dominant interests in the WTO that call for the immediate and total liberalization of trade: “Humanity may in this case require that the freedom of trade should be restored only by slow gradations, and with a good deal of reserve and circumspection.” (Wealth of Nations, Chapter 2)

A political strategy of domination

For the underdeveloped countries, free trade is something else entirely. Eduardo Galeano wrote that “The division of labor among nations consists of some that specialize in winning and others in losing.”

Examined objectively, international trade accomplished several functions in the imperialist system of domination characterized by neoliberal globalization. These functions are as follows: as an instrument of domination favoring the rich countries; as a factor accentuating and perpetuating inequalities; and as a scenario for a virtual war to control current and future markets.

Free trade is not “free” now, nor has it ever been free. Neither is it “trade,” in the classical sense of the term. Its practice does not generate economic growth on its own, nor does it reduce poverty, nor does it impart “mutual benefits” among the sides that trade.

In 1963, Che Guevara said, “How can it be seen as mutual benefit to sell at world market prices primary materials that cost unlimited sweat and suffering for the backward countries, and to buy at world market prices the machines produced in modern automated factories?” (Speech to Afro-Asian economic conference, Algiers, 1963) It was also Che Guevara who coined this precise definition of free trade: “Free competition for the monopolies, free fox among free chickens.” (“On Development,” Geneva, Switzerland, March 24, 1964)

Free trade today is, above all, a rhetorical phrase representing a very organized and coherent neoliberal package expressing the interests of transnational corporations and the governments that represent them. It cannot be reduced to the classical themes that have always appeared in the economics books in the chapter on international trade.

In fact, when it is recommended that Third World countries apply free trade policies-that is, when a Free Trade Treaty is proposed-trade is neither the only nor even the most important part.

In this particular neoliberal rhetoric, free trade matters. But what matters just as much or more is the free mobility of capital-the freedom of capital’s account from the balance of payments that equalizes the market rate of exchange-and the freedom of capital flight, the freedom for transnational capital to invest at its whim and the freedom to contract with a defenseless workforce in conditions of “labor flexibility.”

A new feature of free trade is the ability to link new and advanced technologies with extremely low salaries for the workforce.

Free trade has become the little brother to a financialization of the world economy, in which the sum total of world exports in one year-some $9 trillion-is barely the amount that moves in three days in the transactions of the globalized financial market. This market is characterized by boundless speculation in shares, bonds, derivatives and monetary exchange rates.

So, the first conclusion is that today’s free trade is not only and not so much a commercial opening for goods and services measurable in terms of a commercial balance sheet. It is rather a political strategy for the underdeveloped countries to impose the neoliberal model that best serves the interests of the transnational consortiums-the same ones that are the designers of the world economy.

Hundreds of thousands of Colombian workers struck on Oct. 12, 2004 against IMF-backed economic cuts. |

There is a gulf between the rhetoric of free trade and its real practice.

The big business media transmits a linear and simplistic message. It reduces economic rationality to an irrational and primitive scheme in which the “economic good” is always and forever free trade, struggling against a strict and absurd protectionism that tries to derail the supreme dictates of the market with government intervention. It attempts to decrease imports and to integrate underdeveloped economies based on criteria of regional or sub-regional preferences.

That media does not transmit important realities. For example, the free trade model promotes an advantageous “insertion into world trade” for poor countries that follow its rules. But between 1953 and 2002, the share of underdeveloped countries in the total of world exports fell from 65.6 percent to 26.1 percent, according to a 2002 Oxfam report.

The advocates of free trade tell us that that drop is made up for by the Third World’s increased participation in the export of high technology, rising from 10 percent in 1985 to 25 percent by 2000. But this is nothing more than a statistical illusion. It is far from meaning a rise in scientific research, education and knowledge that would be behind the supposed high technology exports.

This increase is just “intra-firm and intra-product” trade; that is, exchanges within the chains of transnational corporations that take advantage of the planetary mobility of capital. These corporations are “buying” and “selling” among themselves in a caricature of international trade that nevertheless shows up in statistics as exports from underdeveloped countries.

This trade among transnational corporations is currently estimated to be two-thirds of all global trade.

“Intra-firm” and “intra-product” trade, in which a transnational creates a final product as a result of assembling parts produced in countries where costs are lower, especially labor costs, has changed the meaning of the so-called “insertion into world trade.” That insertion is not the expression of a national effort to open a way to supposed “free competition.” Rather, it is the access to internal corporate markets in which the poor countries decide nothing, only passively receiving decisions made by the corporations.

Almost all the rhetoric put out by the WTO, the IMF and the World Bank praising the advance of some countries in the South about the trade of high tech goods means nothing more in real terms than praising corporate processes in which Wal-Mart, Toyota, Nestle and other corporations have decided to disperse parts of production to countries where they are granted greater concessions.

That process is nothing but a new level of corporate domination in which subjugation is more sophisticated, yet it is subjugation nonetheless. There has indeed been an “insertion in trade,” but it has not gone past a subordinate insertion within the corporate chain.

Exports increase, income decreases

If the supposed advance in the trade of high tech goods is only an illusion based on a new strategic corporate model, it is also frightening to note that the South has declined-in the sad and traditional position that comparative advantages have confined it to-in the trade of basic goods.

For basic goods, prices and the corresponding exchange relations are continuing the historic tendency to decline. Trade in this area grows at a slower rate than other types of products. Basic goods are caught in chains of commercialization controlled by transnational consortiums, forcing countries to export ever more of the basic products, whose prices decline the more they are exported.

In effect, the balance of trade for the countries of the South-excluding oil and manufactured goods-has fallen more than 20 percent since 1980. For Africa, the drop has been more than 25 percent. Africa has had to increase its exports by more than a third in order to maintain the same level of imports that it had in 1980.

The IMF, the World Bank and the WTO have induced these countries to maximize exports, but the result has been ominous. While exports of coffee have gone from 3.7 million tons in 1980 to 5.9 million tons in 2000, the income received for these exports fell from $12.5 billion in 1980 to $10.2 billion in 2000.

In addition, at the beginning of the 1990s the income of coffee-producing countries was around $10-12 billion, while the value of coffee sales in the developed countries was around $30 billion. Now coffee producing countries receive only $5.5 billion, while sales in developed countries exceed $70 billion.

This can be explained by the excellent “equilibrium in the power of the market,” created by the wave of mergers and acquisitions that have brought about the restructuring of four or five massive trading companies that buy some 15 million 60-kilogram sacks of coffee every year. Under the infallible dictates of the market, these companies compete against peasant coffee-growers selling on average five sacks per year, according to the Oxfam report.

Among the many other examples of the excellent “realization of free trade” is the supply of bananas to the United Kingdom. Some 400,000 workers participate in the production of bananas, but only five companies have more than 80 percent of the commercial market for them.

Behind the rhetoric

Spokespeople for free trade say that it is a tool for reducing poverty. But the growth in world trade since the 1980s contradicts that claim. At the beginning of the 21st century, the number of people struggling to survive on less than $1 per day has not declined since the 1980s. The same can be said for the number receiving less than $2 per day.

There is no correlation between the growth of trade and the reduction of poverty. Mexico has multiplied its exports, but, in the same period, it also has multiplied the number living in poverty.

The spokespeople for free trade claim that the industrial exports of underdeveloped countries has greatly increased. That statistic is true, yet is also a lie in terms of true development. It is essentially due to intra-firm trade. Moreover, its geographic distribution omits vast areas of the underdeveloped world.

East Asia represents more than two-thirds of the industrial exports of the South and more than three-fourths in the high-output technological sectors like electronics. At the same time, southern Asia, sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America (excluding the growing maquiladora sector in Mexico) have seen a drop in their share of industrial goods. China, South Korea, Taiwan, Mexico and Singapore represent more than two-thirds the value of all industrial exports from the underdeveloped world.

The spokespeople for free trade offer the same recipe for all: export more and open the markets. But the closure of their own markets is the negation of their rhetoric.

The tune of trade liberalization clashes with the double standard that underdeveloped countries apply in order to access their own markets. They apply tariffs four times higher on imports manufactured in the South than they apply to similar products coming from other developed countries.

The poorest countries of the world, the so-called “less advanced” countries, are penalized most-a supreme proof of the cold rationality of free trade. The exports of the 49 poorest countries face tariffs 20 percent higher on average than other countries. If we look at the few manufactured goods they export, the barriers are 30 percent higher. They lose more than $2.9 billion per year as a result of higher protection in the U.S., the European Union, Japan and Canada.

The spokespeople for free trade cannot hide the scandalous reality of agricultural subsidies. Nevertheless, since the Uruguay Round in 1986 they are promoting the idea that they will reduce them. Exactly the opposite has happened: they have increased. They spend in subsidies some five times more than they do for the Official Development Aid.

In another excellent proof of the cold rationality for free trade, millions and millions of small agricultural producers receiving less than $400 per year are “competing” against U.S. and European farmers receiving on average $21,000 and $16,000 a year, respectively, in subsidies. The result is another stain on the prestige of free trade.

The U.S. makes more than 50 percent of world corn exports at a price one-fifth less than the costs of production. The European Union is the largest exporter of white sugar, and its export prices are one-fourth of the costs of production.

This is nothing other than dumping-anathema in the idyllic rhetoric of free trade. But the reality is that the victimizers accuse the victims. Northern protectionism in all its manifestations, tariffs or otherwise, costs the Third World at least $100 billion annually. That is double the amount of Official Development Aid. Despite that, the U.S. and the European Union have presented a total of 234 charges of dumping against southern countries to the WTO.

The discourse of free trade singles out a vanguard role for trade of services as a way for technological progress. But the only services that truly have been liberalized are financial services, exactly where the superiority and convenience of the U.S. is overwhelming. Other services of special interest to the southern countries, like construction services and others, remain closed.

Photo: Bill Hackwell |

Unfortunately, almost the entire South has swallowed the pill of free trade.

The spokespeople for opening trade cannot accuse most of the southern countries’ governments of rebellion or lack of cooperation in the peak years of neoliberalism. Following the sermon of the G-7, they took down tariffs, which created a commercial opening even faster and deeper than that made by the proponents of the plan themselves. The results were so absurd that they would be cause for laughter if they didn’t have such a painful impact on people.

Sixteen countries of sub-Saharan Africa have more open economies than the United States. But that doesn’t put them in first place over Latin America, where 17 countries fall in that category.

The most open economy in the world is Haiti. Various factors come together in a strikingly coherent picture. It is the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere and one of the poorest in the world. Its poverty is painful and cruel.

But since 1986, Haiti achieved the reward as being a totally open economy, according to IMF classifications. It received warm elegies for its exemplary openness.

It is an irrefutable example that obedience to the neoliberal model of free trade is incapable of resolving the problems of poverty and underdevelopment.

Free trade as a plan for today in the South also means capital investment in conditions benefiting transnational corporations. It means buying up the public sector so that the country will be bound and incapable of acting as an agent of internal development. It ensures that the rights of transnational corporations to dominate national markets are respected. It is a policy of competition designed to exterminate the so-called “state monopolies,” while turning a blind eye to private monopolies.

Reform is not enough

To conclude, there are the questions of the future. Can the system of international trade be reformed as trade, or does it need more than reform-a profound, substantial transformation that would make reality not just less bad, but rather the “other world that is possible,” definitely something better to which we aspire?

The reforms in the demands of the Group of 77 within the WTO (a specialized and differentiated treaty, access to markets, elimination of agricultural subsidies, changes aiming to compensate the inequalities in the WTO, etc.) are only because they try to confront grave injustices. They deserve support in the face of the intransigence and the voracity of the G-7 and its transnational consorts. They are also partial. They do not meet the necessary profundity in order to carry out fundamental transformation.

Their partiality comes from the fact that international trade is only a subsystem, a piece in the total machinery that is the imperialist system of domination and exploitation that now uses the financial and monetary pieces as the principal components in its domination.

Advancing trade reforms-if they actually advance-would leave many spaces wide open in which this domination could continue. Some specialized and differentiated treaty, for example, would have little significance if floating exchange rates, freedom of capital flight and the plunder of foreign debt continues to ravage the underdeveloped countries.

The system is integrated and global. The response to its action also has to be global and integrated. That is how the World Social Forum and the Social Forum of the Americas understand it; it is their reason for existence. Trying to look farther, toward the possible world, in order to better build international trade-we cannot be limited by trying to mitigate liberalization a little.

Looking ahead toward the possible and better world to build, international trade cannot be limited to just lessening liberalization a bit. That liberalization has a clear genetic code. It is a child of the capitalist market. The essential goal cannot be hidden: commercial exploitation that comes from the unequal exchange among unequal parts.

The better and possible world is the indispensable utopia that allows us to advance, not lessening liberalization but creating a new standard of values in which solidarity enters into trade to impede the continued situation of trade described by Che Guevara as the action of a free fox among free chickens.

Osvaldo Martinez is the president of the Economic Affairs Commission of Cuba’s National Assembly of People’s Power.