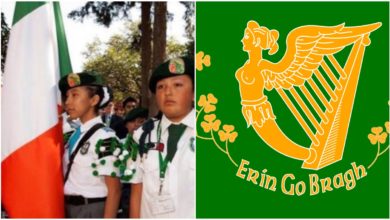

Over 100,000 farmers descended Mexico City on Jan 31 to protest the removal of tariffs on imported beans, corn, sugar and milk—the last remaining trade protections untouched by the North America Free Trade Agreement until Jan. 1, 2008.

Protesters from all corners of Mexico clogged the streets with tractors and buses, raising the slogan, “No corn, no

|

One the nation’s largest labor coalitions, the National Union of Workers, joined dozens of farmers’ groups, including the National Campesino Confederation (CNC), in organizing the march.

According to the CNC, some American farmers get $20,000 in annual government subsidies compared to only $700 in Mexico. The four commodities whose tariffs were lifted are staple items for Mexican workers.

“Before NAFTA we could live off our crops. Now they’re worthless,” said corn grower Luis Valdiga. “What can we do?”

Since its passing, the livelihoods of millions of Mexicans, primarily Indigenous and other peasant farmers, lay in ruins, with many fleeing to the United States for economic survival.

Corn and beans are the mainstay of Mexico’s national consumption, and yet it is now in its majority supplied by U.S. agribusiness. Not only is the country’s production affected, but the kind of production in Mexico is determined from afar. Thus, Mexico’s land produces not for domestic consumption but more and more for the United States.

“We cannot compete against this monster, the United States,” farmer Enrique Barrera Pérez told the Feb. 1 New York Times. Barrera, 44 works about five acres in Yucatán. “It’s not worth the trouble to plant. We don’t have the subsidies. We don’t have the machinery.”

In April 2007, the largest ethanol plant to be built in the world, in Mexico’s Sonora state, was announced. It will be built with investments from the United States as well as India. Its output, from sorghum, sugar cane and beets, will not be for food but instead fuel destined for U.S. gas tanks. Growing demand for ethanol further exacerbates the upward pressure on the prices of staple foods on which poor farmers and workers depend to feed their families.

The removal of the last remaining trade protections is expected to bring the loss of 350,000 farm jobs in Mexico in 2008 alone. As many as 2 million such jobs were eliminated over the last decade.

The struggle of workers and farmers is far from over in Mexico. But their coordinated actions could pave the way for a new, militant movement to emerge.