Last week, 43 years after the Bloody Sunday massacre, the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) arrested a former British paratrooper known only as “Lance Corporal J” in connection with the murder of William Nash, 19, Michael McDaid, 20, and John Young, 17, and the shooting of William Nash’s father, Alexander, who was gravely injured.

In an interview on Radio Free Eireaan, Kate Nash, sister of William Nash, expressed her wish to have closure and justice after four decades of suffering. Nash and the Republican community are pushing for the trial not just of the lowly ranking soldiers who pulled the trigger but rather the British military command structure — led by General Mike Jackson — who gave the orders to murder that fateful day.

Bloody Sunday

Taking inspiration from the Black Freedom Movement in the United States and anti-colonial movements worldwide, the Irish people waged a heroic struggle for equality in the late 1960’s and early 1970’s. Facing inferior housing, job discrimination, police brutality, segregation, religious and national sectarianism in their own land, the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association advocated for an end to these abuses.

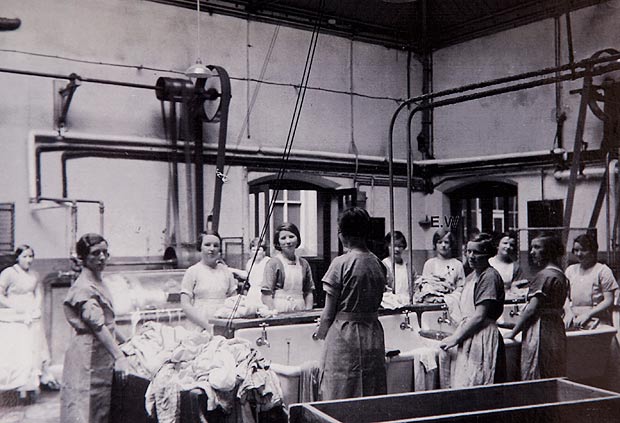

In 1972, the British government enforced a policy of internment, by which any Irish citizen suspected of membership in the Irish Republican Army, the IRA, could be arrested and detained indefinitely without trial. The populations of the Irish Catholic ghettos of Belfast, Derry and other cities in the Occupied Six Counties – led by the mothers, wives and families of the interned — came into the streets in peaceful protest.

On January 30, 1972 British soldiers shot 26 unarmed civilians in Derry during a protest march against internment, killing fourteen of them. Many of the victims were shot while fleeing from the soldiers, while others were shot while trying to help the wounded.

Forty years later, British Prime Minister, David Cameron himself admitted in an apology before the House of Commons that the British soldiers indiscriminately sprayed an unarmed crowd with bullets and slaughtered them even though they posed no threat. A report called “The Sir Desmond de Silva Report” concluded that the Royal Ulster Constabulary — the colonial police force of the Occupied Six Counties — knew the attack was going to take place. This spoke to the collusion that had long existed between the British Government Security Forces and the pro-British militias, such as The Red Hand and the Ulster Volunteer Force, who carried out wanton attacks on the Irish population.

Bloody Sunday, one of the most infamous days in the Irish liberation struggle, sparked “the Troubles,” three decades of internecine warfare waged between the forces of Irish liberation and forces loyal to the British crown. The more moderate wings of the Irish political spectrum, which sought to peacefully work out grievances with the crown, now turned to other means to seek justice.

Scores of young, disenfranchised Irish youth lined up to join the clandestine resistance, the IRA, setting in motion a thirty six year war of tit-for-tat violence that left thousands of victims on both sides.

Antecedents of Struggle

To fully appreciate the courage of the Irish people and to properly contextualize this latest arrest, it is necessary to review some basic Irish history. For centuries, British imperialism was a parasite that leeched off of entire nations for the benefit of a select few. In the 1800’s, the Lords presiding over the House of Commons infamously boasted: “The sun will never set on the British Empire.” While the empire stretched across the globe, one of the greatest thorns in its side was a colony only 327 miles away from London across the Irish Sea.

Since England’s conquest of Ireland eight centuries ago and its reassertion of dominion in the early 16th century, Ireland was in a near constant state of violent rebellion. Every generation since then employed multiple means of struggle, among them the formation of secret societies which threatened, terrorized and assassinated local police, soldiers, landowners and magistrates who enforced foreign rule.

After centuries of gritty resistance reached a fever pitch, the British Empire was forced to grant “home-rule” to the Irish people in the early 20th century. However, the colonial overlords attached many social, political and economic caveats to the new agreement. The chief contradiction was that most of the northern area of the country – referred to as “Northern Ireland” — remained part of the British Empire.

Due to the unstoppable indigenous struggle for freedom, the British offered much of the northern country as free land grabs to a settler population from both England and Scotland that remained loyal to the crown. Like South Africa and Palestine, the north of Ireland was settled by a hostile, foreign population which collaborated with a colonial power to exploit an internal colony. What we are witnessing today is the playing out of this anti-colonial struggle, for one united Republic of Ireland.

Ireland Unfree Shall Never be at Peace

Hunger striker Patsy O’Hara, martyred in 1981, explained the motivation of Irish Republicans:

“We stand for the freedom of the Irish nation so that future generations will enjoy the prosperity they rightly deserve, free from foreign interference, oppression and exploitation. The real criminals are the British imperialists who have thrived on the blood and sweat of generations of Irish people.”

Just as the forty-year long protests of the Bloody Sunday families landed a British soldier in jail, it is the continued unity and sacrifice of the Republican movement that will culminate in the long-awaited reunification of Ireland. One of the chief tasks of Irish and Irish-American fighters today is to learn the glorious history of their ancestors and connect it to the revolutionary, anti-imperialist struggles that are blazing forward today, from Damascus to Caracas, from Havana to Ho Chi Minh City. In the words of Bobby Sands, Tiocfaidh ár lá, “Our day will come!”