Under great pressure from the United States to attack Taliban and tribal fighters in the border regions with Afghanistan, Pakistan has launched a large-scale assault on the tribal region in the northwest of the country. Embroiled in a deep civil crisis, the military campaign is likely to further strain the stability of the U.S.-client state.

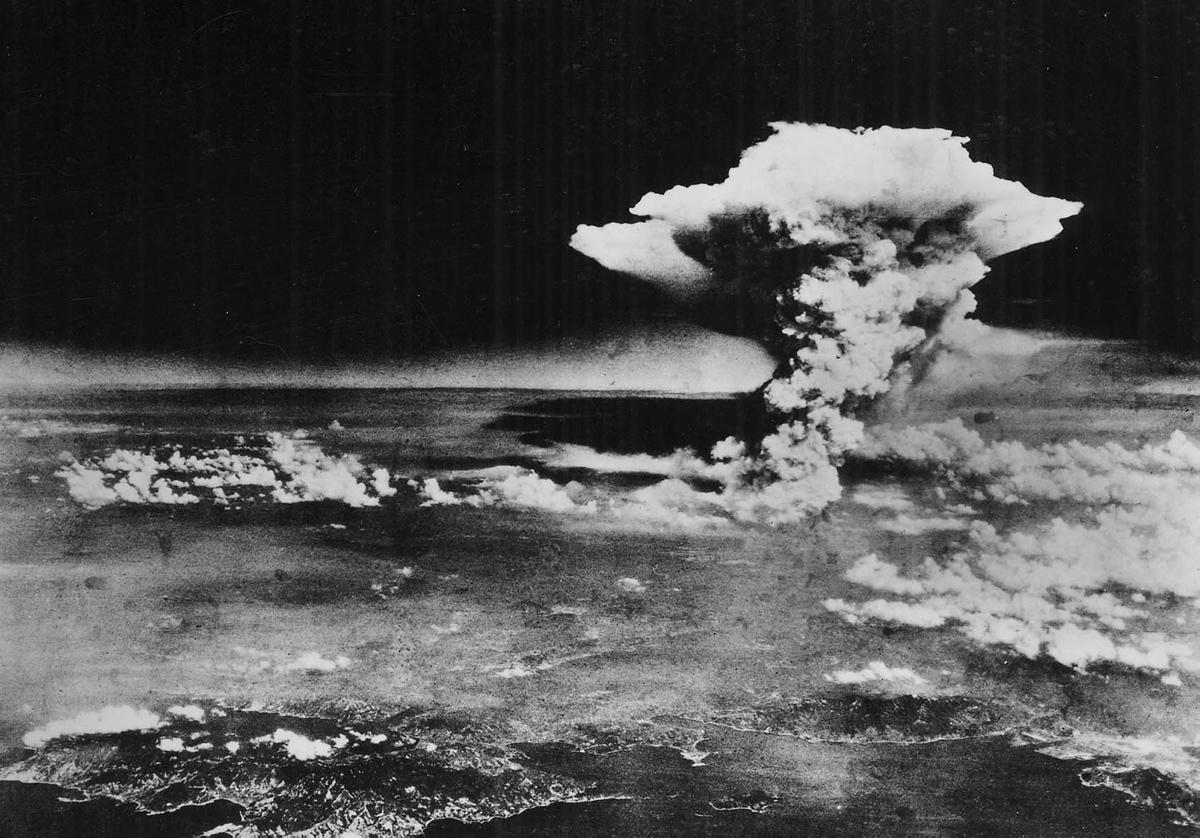

U.S. drones routinely bomb Pakistan |

According to the New York Times, the Obama administration rushed hundreds of millions of dollars of arms to Pakistan in the last month, including transport helicopters, spare parts for attack helicopters and night-vision equipment for F15 pilots. The Pentagon is also relaying targeting information collected by U.S. drone aircraft to the Pakistani military.

In the past eight months, the U.S. has doubled the number of military advisers in Pakistan.

The area being attacked is called South Waziristan. Along with the Swat Valley, South Waziristan is part of the Federally Administered Tribal Area that had long been a semi-autonomous region. The FATA covers a mountainous area in northwestern Pakistan, bordering Afghanistan. For many years, the central government of Pakistan exercised minimal control over this region, allowing local institutions and tribal elders to govern the area.

More than anything, what characterizes the tribal areas is extreme underdevelopment and poverty, courtesy of decades of corrupt pro-imperialist governments in Islamabad. Most of the people live in extreme poverty, and access to basic necessities, such as potable water, electricity and schools, is a luxury not enjoyed by the majority of the people.

The current military assault is really the second phase of a campaign that started May 8, when the government declared a “full-scale offensive” against Islamic fighters in the northwest of the country. Up to that time, Islamabad had shown no inclination to take on the Islamic militants in any kind of sustained fighting.

While there had been occasional clashes, the government had engaged in negotiations with the tribal forces it now calls terrorists. Agreements were reached both under the current civilian government of Zardari and the previous military government of Musharraf.

But the decision of Pakistan’s government to attack has more to do with its subservient relations with the United States than with Pakistan’s domestic circumstances.

In August 2008, a mass movement forced the long-term U.S.-client military dictator, Pervez Musharraf, to step down. Following elections, Asif Ali Zardari, the husband of assassinated Benazir Bhutto, was elected president as the head of the Pakistan People’s Party.

But rather than conceding to the demands of the mass movement, Zardari chose to stay the course, effectively continuing along the path of General Musharraf. His refusal to reinstate Chief Justice Chaudry, one of the key demands of mass demonstrations since Musharraf ousted Chaudry, resulted in Zardari’s loss of popular support. In the end, Zardari survived by capitulating to the mass demand, but in a much weakened state.

Since early this year, the Obama administration, through special envoy Richard Holbrooke, has taken a carrot-and-stick approach toward Zardari’s regime. The stick has been the threat of withdrawing U.S. support, a risk that the weakened Zardari regime cannot afford. The carrot has been promises of $7.5 billion worth of U.S. aid to a country mired in a deep economic crisis. Since 2001, Pakistan has received over $10 billion in aid from the United States, mainly directed at its military.

U.S. aid to Pakistan is really payment for Pakistan’s cooperation in the U.S. “war on terror.” The current aid package of $7.5 billion has come with greater strings than normal. The U.S. government is demanding that the aid be used exclusively in the so-called “war on terror.”

In spite of domestic justifications given by the Pakistani government, Washington is the real reason behind Pakistan’s military assault on part of its own population. The Obama administration succeeded in forcing Zardari to do what the Bush administration had failed to force Musharraf to do—launch an all-out military assault on the northwestern region.

U.S. Senator John Kerry and General David Petraeus made high-profile visits to Pakistani officials during the opening stages of the military campaign. The Obama administration has officially endorsed the operation.

U.S. imperialism struggles to assert control over region

In the ninth year of its brutal occupation of Afghanistan, the United States and its imperialist allies have failed to achieve anything that remotely resembles success. The Obama administration is in the midst of an intense debate on how to go forward. It seems certain that at least some elements of Gen. McChrystal’s recommendations will be adopted, including a surge of up to 40,000 troops. But as McChrystal’s report clearly indicates, the prospects of turning Afghanistan into a stable client state seem remote even with a further surge of forces.

Afghan resistance forces have, for years, freely gone back and forth over the border with Pakistan in the mountainous region, using the Pakistani side as a staging ground. What the Obama administration is hoping for is that Pakistan’s military assault on the Pakistani side of the border will significantly weaken Afghan Taliban and other forces fighting the occupation. With the significant and steady strengthening of Afghan resistance forces over the last several years, the United States desperately needs to turn the tide of the fighting in its favor.

Forcing Pakistan’s government to take this offensive comes with substantial risks. Pakistan’s weak central government is in peril of further weakening as a result of its military adventure within its borders. For Pakistan’s military, winning a sustained battle in the rugged terrain of the mountainous area with few roads is a huge challenge. Further, as recent events have proved, the besieged forces in the area have the capacity to inflict significant damage to Pakistan’s government and military outside the Swat Valley and South Waziristan.

It is hard to determine the level of success of Pakistan’s military offensive, in which 30,000 soldiers have been deployed. Reporters are banned from going into the area, while Pakistan’s military dispatches daily reports of military victories. Keeping with the tradition of their U.S. masters, Pakistani military leaders call all victims of their massive aerial bombardments on homes and villages “insurgents ” and “terrorists.” But it is clear that the military has encountered stiff resistance. Given the disparity of forces, both in terms of troop numbers and weaponry, there is little doubt that Pakistan’s military will take the key towns of South Waziristan, as it did in the Swat Valley earlier this year. The question is the costs that Pakistan’s government will have to endure by holding these areas, in the region and beyond.

Across the country, militants have carried out a wave of far-reaching attacks on the military, police and other targets. On Oct. 21, militants staged a daring attack on the Pakistani army headquarters in Rawalpindi, taking the fight to the doorstep of the powerful security forces. At least six military officials were killed. On Oct. 23, there was an attack on a major air base in Islamabad, the capital, killing seven people. On Oct. 25, militants shot down a Pakistani military helicopter. In the first three weeks of October, nearly 200 people were killed in the attacks on various targets in major cities.

U.S. hands off Pakistan!

The danger to the survival of Pakistan’s government does not primarily come from the Taliban-aligned forces, whose popular base does not significantly extend beyond their home base in the tribal regions. Much of Pakistan’s population lives in large metropolitan areas, where huge mass protests against Musharraf made history in ending the military dictatorship. The political character of the opposition in most of Pakistan is far different from that of the tribal regions.

An editorial in the Lahore-based “Nation” newspaper accused the government of “jumping onto the U.S. bandwagon in a misdirected war on terror” and called the “American pressure to use military force against the militants” a “U.S.-laid trap” as part of a “larger hidden anti-Pakistan attack.”

The real danger for the stability of Pakistan’s U.S. client state is that much of the population sees the attack on South Waziristan, and the resultant insecurity and instability, as another example of the capitulation of Pakistan’s government to Washington. This may give rise to another round of mass protests to force the will of the masses on a subservient regime that launches a criminal military assault in the interests of imperialism.