On Oct. 9, 2006, North Korea shocked the world when it announced it had successfully detonated its first nuclear bomb. In doing so, it became the only member of the “nuclear club” without formal and friendly relations with the United States.

|

The corporate media immediately declared that a terribly tragedy had befallen people in the United States, and peace-loving people worldwide. Kim Jong Il, falsely characterized as a wild and unpredictable tyrant, now had an enormous weapon at his disposal, according to the hyped media coverage.

The U.S. ruling class went into a frenzy. Bush—who in 2003 named North Korea as part of the “axis of evil”—called the successful detonation “a grave threat,” and made veiled war threats. Democratic Party lawmakers used the opportunity to talk tough about the “war on terror,” bemoaning the fact that the Iraq war quagmire prevented effective hard-line action against North Korea.

With the war fever heating up, it seemed that the decades-long conflict with North Korea could escalate. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice immediately discussed the possibility of a full-scale naval blockade of North Korea, which Pyongyang declared would be considered an act of war. Was another Pentagon military adventure on the horizon?

One year later, however, North Korea is closer than ever to achieving its desired foreign policy objectives: a lifting of sanctions, normalized relations with the United States and its allies, and a peace treaty to officially conclude the Korean War.

On Oct. 2, for only the second time in history, a South Korean President—Roh Moo-hyun—visited Pyongyang. Relations seem to be improving so steadily that South Korean real estate speculators are thinking of building a golf course directly south of the Demilitarized Zone, which despite its name, is the most heavily armed border in the world. Just a few years ago, that land could not even be given away.

As for the United States, it recently agreed to unfreeze North Korean assets in international banks and began delivering some its promised energy and aid. To the disdain of conservatives, chief U.S. negotiator Christopher Hill has openly discussed the removal of North Korea from the U.S. list of terrorist states.

A U.S. firm—with explicit backing from Washington—has expressed interest in a joint development project in northern North Korea. Even the New York Philharmonic announced that it might play in Pyongyang as soon as February.

On a similar note, Taku Yamasaki, a senior Japanese lawmaker and former number two in the ruling Liberal Democratic Party, predicted on Oct. 10 that diplomatic relations would be established with North Korea within the next year.

Japan, the long-standing imperialist power in the Pacific and former colonizer of Korea, has been irreconcilably hostile to North Korea since its 1945-50 socialist revolution. A year ago, Japan was among the most belligerent in its denunciation of North Korea’s nuclear test.

Ending the stalemate

How did North Korea win such sweeping concessions in the course of a year? Why is the region closer now to a formal peace than ever before? Why are the imperialists—who have strangled the underdeveloped world with no restraint since the overthrow of the Soviet Union—now starting to loosen their grip? What changed the political calculus so dramatically?

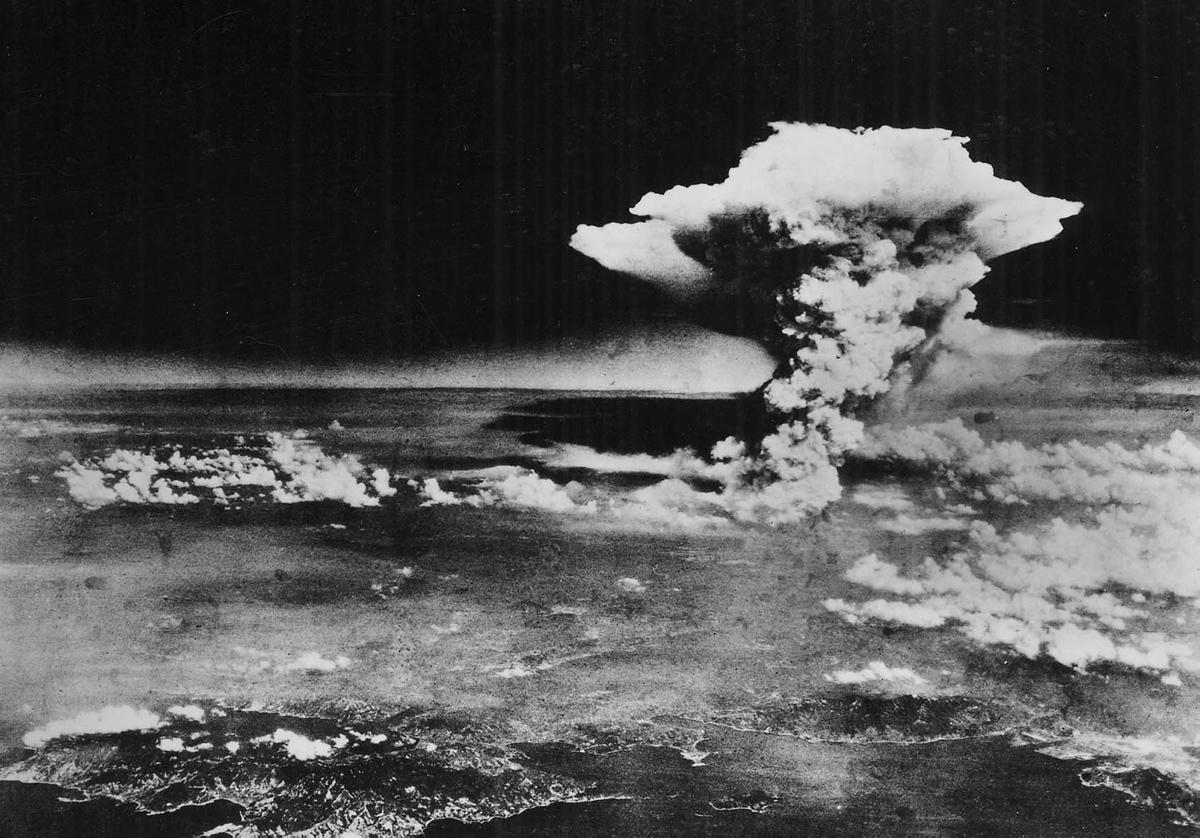

The bomb changed everything. By exercising North Korea’s right to self-determination and self-defense and detonating a relatively small nuclear weapon—especially compared to the Pentagon’s arsenal of about 10,000 deployed or reserve nuclear weapons—the North Korean government was able to break through the diplomatic stalemate.

This stalemate did not stem from what the capitalist press calls North Korea’s “broken promises.” To the contrary, it was the United States that consistently violated the 1994 General Framework Agreement.

In return for North Korea disabling its “heavy water” nuclear energy reactors, the Clinton administration promised to build “light-water” reactors to fulfill the country’s energy needs. Eight years passed before the United States began building even the first reactor.

Both the Clinton and Bush administrations, although they differed on tact, had “regime change” as their fundamental goal. In other words, they aimed for the return of capitalism in North Korea.

They could make all the demands and set all the terms, because they knew North Korea had few cards to play in return. That was the basis of the diplomatic breakdown. Washington felt no pressure to respect North Korea’s sovereignty.

But on Oct. 9, 2006, North Korea pulled an ace out of its sleeve. It spoke in the only language that imperialism understands: military might.

At once, the country struck a blow to the U.S. foreign policymakers, who reserve to themselves the right to distribute the world’s weapons of mass destruction. The Pentagon’s National Security Strategy—which is followed by both major parties—requires unquestioned military supremacy and the virtual disarmament of any state that refuse its dictates.

North Korea’s calculated risk to detonate a nuclear weapon despite the overwhelming military supremacy of Washington seems to have paid off. This is the reality to which the liberal establishment has blinded itself.

The new diplomatic achievements between the White House and North Korea are not a product of the Bush administration coming to its senses. The imperialists in power are no more humane, and no less bloodthirsty, than a year ago.

Indeed, this is why North Korea is still a long way from winning the peace and normalized relations that it deserves. But if “peace” is approaching, North Korea must be credited, not Bush.

While the Bush administration has been pushed back again by the steadfastness of the leadership in North Korea, it would be na?ve to think that this struggle is coming to a close. If there is a thaw in U.S-North Korean relations, it must be viewed as a momentary lull or a temporary truce in the struggle between two antagonistic social systems.

The U.S. strategy may shift from outright military conflict to another form of subversion, such as the type employed in Easten Europe in the late 1980s.

Washington will seek to nurture a so-called cold counterrevolution so that the vast land, industry, and natural resources of North Korea will be returned to private hands and made available for renewed exploitation by western corporations and banks.

The struggle between U.S. imperialism and North Korea may be entering a new phase.