On Oct. 28, the Mexican government sent thousands of riot police into the city of Oaxaca, where teachers and other workers had held the main square since June. While the cop attack dislodged the protesters from the zócalo, thousands of people organized by the Popular Assembly of the Peoples of Oaxaca continued to occupy strategic parts of the city. Updates on this developing struggle can be found at pslweb.org.

Dr. Gilberto López y Rivas is a professor of ethnology and social anthropology at the National Institute of Anthropology and History in Mexico City. He is a longtime progressive Mexican activist who writes extensively on the political and social struggles taking place in Mexico and Latin America. He is a contributing writer for La Jornada newspaper and other Mexican publications.

Socialism and Liberation’s Gloria La Riva interviewed Dr. López y Rivas at the “In Defense of Humanity” conference in Rome, Italy, on Oct. 14, 2006. This interview first appeared on pslweb.org on Oct. 27.

You have followed closely the struggle taking place in Oaxaca and written in support of it. Can you comment on what is happening there?

In Oaxaca, there is a situation of great complexity and interest from a historical point of view, in which basically people’s power is developing out of a conflict that began strictly as a labor struggle. It arose after the state’s governor carried out repression against that struggle and it has now become a movement called “The Popular Assembly”—and this has to be emphasized—“of the Peoples of Oaxaca” or APPO.

APPO is composed of representatives of all political sectors, unions from Oaxacan society, and also representatives of the Indigenous peoples of Oaxaca. In APPO, there are years and decades of experiences in the building of power from below, the experiences of the Indigenous communities, of the organizations that are participating in this civic insurrection. It is a civic insurrection that is being conducted without a single shot being fired by the insurgents, and is based on a broad and profound popular mobilization.

After the very violent repression of the teachers in Oaxaca’s historic center, the civil society came out in support of this movement. Since then, we see the development of what is now known as APPO. The means of communication have been taken over, television, radio. A process is taking place that was already present in Mexican society, but in a truly surprising way.

Radio APPO operates 24 hours a day and there is already developed a system of communication, coordination, messages, ideological struggle that has not existed recently or in the contemporary epoch in Mexico. The situation has obviously unleashed a furious campaign by government and business of the Mexican right and ultra-right.

Those sectors clearly see a danger of this extending to other states of the republic, which, in fact, is taking place. There have been proposals to organize a Popular Assembly of the Peoples of Michoacán and a popular assembly of the peoples of Guerrero.

APPO is faced with a fierce and authoritarian reaction by extra-legal police forces and paramilitaries that are threatening the movement. It has already taken the lives of six people at this point, numerous wounded. It has forced the popular movement to resort to defending itself with barricades.

This form of struggle was very common in France, especially in insurrectional Paris in 1848 and later, in the Paris Commune. It has led various analysts, especially Luís Hernández Navarro, to call this process the Oaxaca Commune. And it certainly is, in the sense that APPO operates with the principal of representation and the principal of instant recall. This means that those people who do not carry out the agreements of the assemblies are immediately replaced or recalled. Everything is decided in the general assembly of the direct delegates.

At one point, APPO was on the verge of being repressed by the Marines. The Army had refused to intervene directly, demanding instead that the president issue a written order and suspend individual rights. The secretary of defense did not want a repeat of the 1968 events. So, he demanded a presidential order so that any military action would have the cover of constitutional legality.

This has not happened, however, because, as the possibility of repression grew closer, APPO decided to carry out a march to Mexico City and it took the power establishment completely by surprise. It frustrated their plans of repression, although the provocations and night attacks continue.

The march reached Mexico City and settled in front of the Senate because that governmental chamber has the power to revoke one’s mandate. The principal demand of APPO is that Ulises Ruiz, the governor of Oaxaca, be removed.

It is evident that we are witnessing a movement of great historical and political depth. There are diverse sectors in this movement; it is not homogeneous. There are socialist sectors. It is said that there are sectors of one of the armed groups that operate in Oaxaca, although this has been strongly denied. There is also support from the EZLN, although the EZLN says it does not want to interfere in APPO’s affairs. It wants to avoid any pretext for more repression.

APPO is now the most important social and political conflict, in terms of the conjunctural immediacy, but also for the profound radicalization of that movement.

I have been listening to Radio APPO and I can say that it is incredible for the listening audience, the tension that the people are living night and day in vigil. The form of communication, the testimonies that many times end in crying, is extraordinary.

Is the radio situated in a station that already exists and is occupied, or was it created?

They took over a radio station and are transmitting from there. The radio is protected by a group of compañeros and compañeras. Barricades have been set up. It is one of the military objectives of the government because of the importance that this radio has. I’m telling you about the radio because it is truly stunning. In Mexico there has been a fierce control of radio, television, of the means of communications and this has impacted the audience immensely.

The people are able to know when help is needed at one of the barricades.

The other night I turned on Radio APPO, and all of a sudden I hear the old song, “Bandera Roja” (Red Flag) which I had not heard for 40 years. Their use of the radio is one of the many means of communication. They use whistles, fireworks to communicate. Several fireworks mean danger; there is a whole form of communication.

Does the Oaxaca insurrection have roots in the state’s history?

When the European Union asked my wife and me to do a study of the Indigenous autonomous communities four years ago, we proposed to study two states, Chiapas and Oaxaca. Oaxaca is a state with 16 recognized ethnicities, among them the Mixtecos, Zapotecos, Triquis, Amuzgos—there are Amuzgos in Oaxaca and Guerrero—the Chatinos, 16 ethnicities in all.

Oaxaca has 579 municipalities and around 400 are traditionally governed, that is, by Indigenous governments chosen in assemblies—instead of three-year terms—each year. It is a state with one of the most advanced legislations on Indigenous issues. So, Oaxaca is distinguished by its multi-ethnicity and by the struggles that have taken place.

Section 22 of the independent teachers union is one of the most combative in the union, which is the largest union in Latin America with a membership of more than one million. They are teachers in primary- and secondary-level schools.

The state has a very important representation of Indigenous peoples in their experience as victims and as protagonists. They are among the poorest in the republic, but the Indigenous movement has also developed positions successfully adopted in the San Andrés Dialogue. The position of communal autonomy is based on the importance of the community, the community assembly and self-government, for their identity.

I and many others as well consider Oaxaca to be the quintessential Indigenous state in contemporary Mexico.

Is that because of the percentage of population or the leadership that you describe?

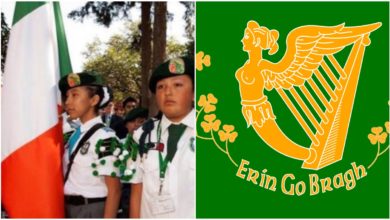

“Murderers.” Riot police stormed Oaxaca on Oct. 28. Photo: Henry Romero/Reuters |

Both aspects. The presence of the Indigenous peoples is large in demographic terms, but not a majority. The states that are predominantly Indigenous are Yucatán or Quintana Roo, but Oaxaca is where the Indigenous presence is ubiquitous.

Oaxaca is also the base of one of the armed groups, the Revolutionary People’s Army (EPR).

Therefore, in Mexico there are four major processes underway, which in one way or another converge in the same political and territorial space. The APPO, the Zapatistas and the Other Campaign, the movement of the Democratic National Convention headed by López Obrador, and the armed groups.

Almost nothing is said about armed groups, but there are at least four groups with firepower and size, with professional combatants under arms on a permanent basis. There are at least five or six other groups that issue communiqués or conduct armed actions from time to time. So, we are talking about armed groups with a basically Marxist ideology, with the line of prolonged people’s war.

For example, in this process they have been publishing a large number of communiqués in recent weeks. It is a force that is present and has to be considered.

What role does the labor movement have in Oaxaca with the APPO?

Oaxaca is predominantly a state of agriculture and services, particularly tourism, as well as artisanry. There is practically no industry and it relies heavily on the remittances that are sent from the United States.

I conducted research in a town called Putla with a method used by the anthropologist Manuel Gamio in the 1920s to find out where the remittances came from. The southwest was still the area chosen by the Oaxacan population to emigrate: California, Texas—especially California.

There were also a lot of remittances from Chicago, from the Twin Cities area. It is a very poor state which relies on agriculture, tourism, artisanry, remittances and now, we see the presence of the scourge of narcotrafficking. In almost all the Indigenous territories, narcotrafficking is evident.

Has the North American Free Trade Agreement, NAFTA, had a major effect on the state?

It is mainly being affected by the projects to which NAFTA has opened the door. There is a very dangerous one called the Isthmus Project that will create a corridor to more or less substitute the Panama Canal. It is a project that would transverse Tejuantepec. It is actually not a canal, but rather a means of transcontinental transport by railroad containers. It is one of the most threatening projects planned for Oaxaca. Oaxaca is rich in biodiversity and, for that reason, it is greatly sought after by capital.

Foreign capital or Mexican capital?

It is no longer possible to speak of Mexican capital. Practically all the speculative and industrial sectors have been or are in the process of being tied to the transnational market. There is no longer a distinction between the national bourgeoisie and a bourgeoisie tied to transnational capital. Globalization has, in effect, internationalized all sectors and social classes, including the working class.

It is said that there are 56 billionaires in Mexico. Does this signify a growth of the national bourgeoisie?

It is a class that has capital, luxury residences in Miami, Houston, and for some of them the more exquisite are in Spain or France. It is a cosmopolitan class that aspires to live in the United States. In fact, some have chosen to change their residence to the United States. Regarding their preference, it is what Carlos Monsivais has labeled as “the first generation of U.S. people born in Mexico.”

I say this to mean that they are Mexicans who think much like Vicente Fox and I refer to the term that he uses, “Americans.” Mexicans in the left do not use the term “American,” we have always used “gringos,” “Yankees,” or “people from the United States.” Generations in the past would use “American,” but now it is used by that privileged sector that is enamored of the United States. And Fox—very representative of that—uses the term “American.” Terminology always has political and historical connotations, and we are very conscious of that in referring to people of the United States.

The internationalization of the Mexican market means that the capital is not based exclusively in Mexico or with Mexicans. It is also an appendage of European capital, the European Union as such and Spain in particular, which has a strong political as well as economic presence in Mexico. But basically the control is by the U.S. corporations.

You published a significant critique of the Mexican bourgeoisie in La Jornada.

Yes, the theme is the so-called “National Unity.” This theme is of great importance to Marxists because the term has given rise to many erroneous interpretations. One in particular has to do with the idea that the nation, the homeland, rests in the bourgeoisie. The Communist Manifesto says that “the workers have no nation,” but the context of that phrase is that the workers have no vested interest in that homeland, they are only subjects.

For many years in Mexico, we have promoted the concept of what I call, “revolutionary patriotism.” This means that we Marxists do not deny our close identity with the country, and we proclaim our love for the homeland as Martí did, as Lenin did, but not in the bourgeois sense.

When there is a crisis as the current one in Mexico, the bourgeoisie uses its concepts of homeland—state of law, patriotic symbols, the republic’s institutions—in order to deceive and conceal its dictatorship, its authoritarianism, repression and its class interests. So, the article that I wrote, “National Unity,” was written as a means to recover the meaning of nation. The Zapatistas, for example, do not negate the idea of the nation. They use the national flag, the national anthem and salute to the flag, but they give it a different meaning, which is the homeland of the exploited, of those who are discriminated and segregated.

In any crisis, the bourgeoisie always says that we should all unite for the homeland. Bush forms a department of state terrorism and repression and what name does he choose? “Department of Homeland Security.” National unity is used frequently to deceive and hold people captive. So you have people go to Iraq thinking they are going there to defend the patriotic values of the United States, when, in reality, what they are defending is capitalism and the interests of the U.S. ruling class.

They believe that imperialist war is patriotic. The intelligence agencies of the United States and the media that serves them refer insultingly to anyone who resists them as a traitor. It is extremely important for them to promote the idea that anyone who is against capitalism is against the homeland. For them, homeland really means capitalism.

That is why destroying the myth of the nation as conceived by the bourgeoisie is a historical necessity and a politically strategic necessity.

How do the forces in Oaxaca see that theme of national unity?

Some sectors in APPO believe in the concept of classes. Not all, but at least with the idea that the struggle is a confrontation between rich and poor, between the powerful and dispossessed. A profound class consciousness does exist, exacerbated by the events of the last two months.

The people have learned more in that time than has been learned in years because the struggle, the confrontation has exposed everyone—the intellectuals, the political parties, the television commentators, the newspapers. Everyone has been exposed and has taken sides.

The intensity of this confrontation is unprecedented. There is scorn for those who have sold out, for the class traitors—for example, the writer Carlos Fuentes, who made a declaration that the presidential elections have never been as transparent as the ones that just took place.

Fuentes was considered as someone who sympathized with the left, but on this occasion he has become an ally of the government. It is the same with other intellectuals, including those who were Marxists and who now adopt the ideas of the ruling class.

That is why I believe the need to separate, to strip the national question away from the bourgeoisie is a historical necessity. I think that the Zapatistas are very clear about this, and that APPO is reaching these conclusions.