John Black, a lifelong socialist and advocate for workers’ and civil rights, died on Mar. 7 after a prolonged illness. He was 85 years old.

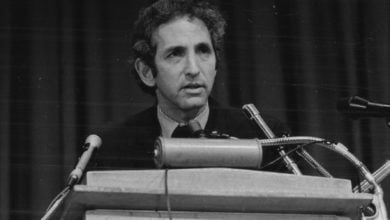

John Black spent decades as an organizer and leader of hospital and health care workers. Photo: 1199 |

Black was born in Germany on Jan. 17, 1921, the son of a U.S. oil executive and a German citizen. It was a turbulent period in Germany. Just two years earlier, on Jan. 15, 1919, German revolutionaries Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg had been murdered as part of the effort to crush a revolutionary workers’ movement inspired by the 1917 Russian Revolution.

The right-wing effort succeeded in crushing the German workers’ movement in the short term. But tremendous economic hardships following World War I pushed millions of workers, exhausted by war, toward socialism. Following the worldwide economic crisis of the 1930s, the socialist and communist movement in Germany was growing again.

Black was swept into that movement at an early age. He joined the Communist Party’s youth group when he was nine years old, at a time when the party was involved in daily street battles with the growing fascist Nazi movement led by Adolph Hitler. He took part in anti-fascist activities in his school and in Berlin’s working-class neighborhoods. Those activities were fraught with danger.

He described how even an activity that activists in the United States today take for granted—handing out flyers—was a carefully organized and planned activity. Teams of activists would sneak onto rooftops to place a box of leaflets on a board overhanging the street below. On the other end, the teams would put a pail of water to balance the weight of the box, and then punch a hole in the pail. When enough of the water drained out, the leaflets would fall to the street below—after the team had made it out of the building and avoided detection.

He would spend nights painting communist slogans like “Berlin stays red” on walls throughout the working-class neighborhoods, all under the cover of darkness.

In his teens, Black worked as a courier for the Communist Party, carrying anti-fascist messages across the German border to Czechoslovakia.

As many of his comrades were rounded up by the Nazi police, Black fled Germany in 1939 to London. In 1940 he moved to New York. He joined the Socialist Workers Party, and over the next decades he gained experience in union and political struggles in New York, Seattle and Buffalo.

A socialist organizer

Although he had first-hand experience with some of the reactionary policies of the Soviet-oriented Communist Parties, Black soon became uncomfortable with the SWP’s version of anti-Stalinism. Especially after World War II, when U.S. imperialism re-oriented almost exclusively toward confrontation with the Soviet Union, the SWP’s version of anti-Stalinism dovetailed too closely with the prevailing anti-communist propaganda of the times.

While in the SWP’s Seattle branch organizer, he aligned himself politically within the SWP with Sam Marcy and Vince Copeland, who were struggling to win over the SWP to a revolutionary orientation on the major issues of the day. For example, Black gave a series of lectures in Seattle and in other branches shortly after the 1949 Chinese revolution promoting the view that a socialist revolution was underway there and that it deserved the support of the U.S. working class movement.

In 1959, he joined Marcy, Copeland and a handful of other militants in Buffalo forming Workers World Party. In the first issue of Workers World newspaper, in March 1959, he wrote an article defending the socialist German Democratic Republic against NATO threats to attack East Berlin.

It was during his years organizing in Buffalo that he met his wife, Bernice, who was a member of a Black community theater group. The two married weeks after meeting in 1960. The marriage would last Black’s lifetime.

A pioneering union leader

Beginning in 1961, he began working with Local 1199, then part of the Retail, Wholesale and Department Stores Union, organizing hospital and healthcare workers. The prevailing view in the labor movement at the time was that healthcare workers, primarily women, could not be organized. He was determined to prove that view wrong.

This project would consume much of his energy over the next 25 years—leading strikes, union recognition elections and contract negotiations in New York City, New Jersey, Philadelphia and central Pennsylvania. He founded and was president of District 1199P, which represented hospital and nursing home workers throughout Pennsylvania.

He would often say, “I came to know Pennsylvania by its hospitals and its jail cells.”

As a union leader, he always tried to break down the anti-communist prejudices that characterized the Cold War climate. He participated in delegations to the Soviet Union, East Germany, Bulgaria and other Eastern European countries at a time when U.S. government hostility toward the socialist countries was at its peak.

‘Free Mumia!’

After retiring as local union president and international union vice president in 1986, Black remained active in local and national political struggles. He was a regular at anti-war and social justice activities in his hometown of State College, Pa.

In 1992, Black returned from a trip to Germany committed to take up the case of death row political prisoner Mumia Abu-Jamal, who was then in prison just 30 miles from State College. At the time, Abu-Jamal’s case was little known outside of Black activist circles.

“I found it amazing that there was more awareness in Germany about Mumia’s case than there was in the United States,” Black remarked.

He played an instrumental role in setting up the Committee to Free Mumia Abu-Jamal in State College. He frequently visited Mumia in prison, even after he was moved to a new facility outside Pittsburgh. He also developed a close working relationship with Pam Africa and the International Concerned Family and Friends of Mumia Abu-Jamal.

While this defense work on Mumia’s case in State College seemed isolated at first, it laid the basis for much wider activism in coming years.

In his first book “Live from Death Row,” Abu-Jamal acknowledged John Black’s contributions. “John and Jenny Black, two from the same fire,” he wrote, referring to Black and his daughter, who also devoted intense energy to Mumia’s cause.

For four years, Black hosted the weekly program “View from the Left” on Penn State’s WPSU radio station. Frequent airings of Abu-Jamal’s radio commentaries on the program ultimately led the station to cancel the show.

Internationalism

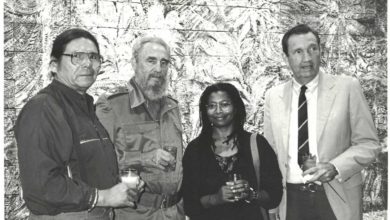

In his later years, Black took every opportunity to challenge U.S. imperialism’s foreign policy. He traveled to Cuba twice in defiance of the U.S. government’s travel restrictions against the socialist country.

In 2000, Black participated in a delegation to Iraq in order to document the damage inflicted on the Iraqi people by a decade of economic sanctions following the first Gulf War. While on that trip, he suffered a severe heart attack.

Well into his seventies, Black continued to write on the international communist movement. After his 1993 pamphlet “Mutiny in the Indies,” an account of working-class solidarity between colonial Indonesian sailors and Dutch military personnel in 1933, he devoted tremendous research efforts into the life of Indonesian communist Tan Malaka.

Although his health declined, he never wavered from his unflinching opposition to racism and U.S. imperialism, and his support for workers’ struggles in the United States and around the world.

His life was dedicated to the cause of the working class and oppressed people. For the revolutionaries who he met and influenced, John was a link in the chain of communist continuity that unites the working class movement of today to its origins in the 1848 revolutions in Europe.

Like many other working-class leaders and activists—some of whom became well known and some of whom worked tirelessly without recognition—the ultimate monument to his life will be a socialist revolution in the United States.

Articles may be reprinted with credit to Socialism and Liberation magazine.