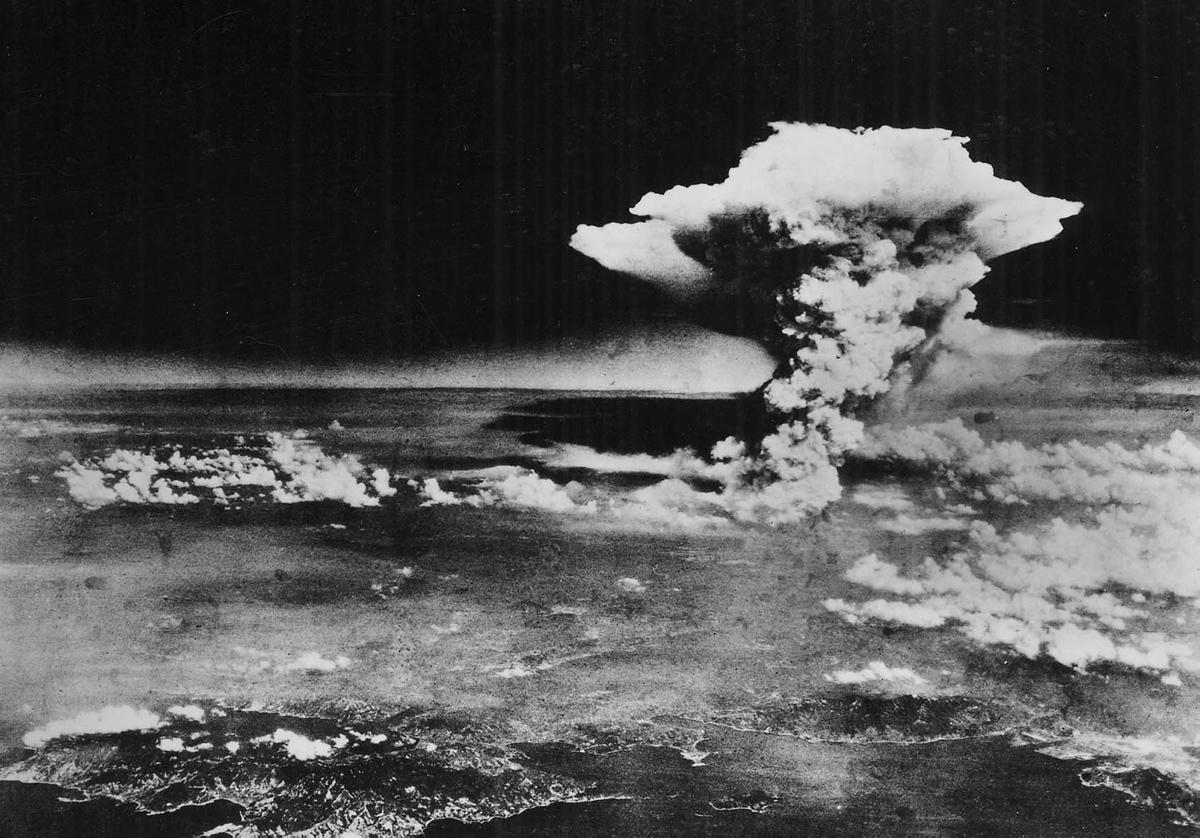

Communist guerrillas now control 80 percent of Nepal. Photo: Pete Pattison |

On Jan. 3, 2006, explosions targeting government offices rang out across the south Asian country of Nepal. The attacks, launched by the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist), known as the CPN(M), came less than one day after the People’s Liberation Army, an army which is led by that party, called off a four-month-old unilateral ceasefire in the unstable kingdom.

In subsequent days, more intense attacks followed. On Jan. 11, more than one thousand armed insurgents stormed over half a dozen government offices, including an army barracks and police post in western Nepal. The insurgents ended the ceasefire because the Royal Nepalese Army had murdered “dozens of unarmed Maoist cadres after apprehending them during the unilateral truce,” according to CPN(M) leader Prachanda. (Kantipuronline.com, Jan. 2)

For 10 years, the insurgency has been fighting to replace the old political structure with a new one free of corruption and exploitation. The CPN(M)’s stated short-term goal is to establish a constituent assembly that would include all of Nepal’s political parties, including bourgeois democratic forces. But unlike the other Nepalese political parties, the CPN(M) ultimately seeks a secular, socialist republic, radical land redistribution, universal education and medical care, equal rights for women and men and all ethnic and religious groups and an abolition of the caste system.

Nepal’s seven main parliamentary parties also blamed the “autocratic government” of King Gyanendra for the ceasefire’s breakdown. Known as the “seven-party alliance,” this grouping does not include the insurgent CPN(M). “We thoroughly studied the Maoist statement announcing the end of ceasefire, and concluded that the current autocratic royal regime is the main guilty party for creating such a situation,” said Madhav Kumar Nepal, a parliamentary party leader.

No group in the seven-party alliance supports or participates in the armed insurgency. Until last February, these groups held 190 of 205 seats in parliament and many supported the King’s army against the insurgency.

United front against the monarchy

The basis for the current, unprecedented political unity against the monarchy was laid one year ago, on Feb. 1, 2005, when King Gyanendra sacked the country’s prime minister and parliament for the second time in just over two years. The king declared emergency rule, banned all political activity and fully centralized state power in himself.

Gyanendra claimed that his power grab was done in the name of “peace” to restore Nepal’s “multi-party democracy” and to quell the powerful insurgency in the countryside. Taking a cue from his U.S. imperialist backers, he invoked the phony war on terror as an underlying motive.

But the real reason behind the royal coup was the King’s ever-rising fear of being toppled from power. He believed the parliament and the few democratic rights left in the country were impediments to defeating the insurgency.

|

In November 2005, nine months after the royal coup, all parties—including the CPN(M)—agreed to work together to end the harsh rule of the king. They did not do this out of ideological unity. The reason that the parliamentary parties have come out in opposition to the monarchy and formed a tactical alliance with the communist insurgents is the strength of the insurgency itself.

The united front of all parties has since pledged to boycott the municipal elections scheduled for Feb. 8, 2006, calling them a farce. Gyanendra called the elections to appease his U.S. imperialist and Indian backers, who are increasingly worried that his naked power grab has backfired and created new support for the communist-led insurgency. Seizing absolute power does not gel with the U.S. government’s talk of “spreading democracy” around the world.

The armed rebellion, coupled with the united front, is making King Gyanendra’s hold on absolute power more tenuous each day.

Poverty and underdevelopment

It is not surprising that a revolutionary uprising has swept the country. Nepal is one of the poorest and least developed countries in the world. Its economic system is tied to the world capitalist market, although strong remnants of feudal social relations remain. It lies on the south side of a 500-mile-long section of the Himalayan mountain range. China borders it on the north, and India surrounds it on the east, west and south.

Nepal gained formal sovereignty in 1816 after a two-year war with the British, who ruled India at the time. After Indian independence in 1947, the new bourgeois or capitalist rulers of India replaced the British in exercising semi-colonial control over Nepal. India’s influence on Nepal’s politics and economy has wavered rarely since then. The whole country is subordinate to and dependent on India and imperialist countries like the United States.

Agriculture is the mainstay of Nepal’s economy. It accounts for more than 40 percent of Nepal’s gross domestic product. Industry is much smaller, primarily based on processing of agricultural produce and related activities. Urban industrial workers are a tiny minority of the workforce.

Poverty in Nepal is grinding. Over 40 percent of its more than 27 million people live below the poverty line, with the gross national income averaging $240 per person, according to the World Bank. The average income can be as low as $40 for women, people from lower castes, dalits or “untouchables,” and ethnic and religious minorities.

More than 85 percent of Nepal’s people are peasants in the countryside. They are uniformly poor and suffer malnourishment and exploitation by corrupt officials, landlords and moneylenders. In rural areas, people lack social services, basic sanitation, clean water and solid infrastructure.

The dictates of globalization are continually driving young Nepalese off their land. The relatively underdeveloped means of planting and harvest are unable to compete with large-scale capitalist commercial agriculture in other countries. In Nepal, unemployment and underemployment are at levels among the highest in the world.

Discrimination against women is deeply entrenched in the current social system. Women are severely oppressed and treated as inferior in every facet of society. Literacy rates and life expectancy are much lower for women than men. Women often face domestic violence and harassment with no legal recourse.

Poverty plagues Nepal’s countryside. Photo: Reuters/Gopal Chitrakar |

Nepal’s prevailing caste system, based on feudal interpretations of the Hindu religion, categorically relegates people into a hierarchy of social positions. In the caste system, people are born into a social group or class. People from the lower castes are denied equal access to social, economic, political and legal resources. There is no changing one’s caste, either up or down.

Around 40 percent of Nepal is comprised of non-Hindu ethnic minorities and indigenous people. None of these sectors are part of the caste system and, therefore, enjoy even fewer rights than the Hindu majority.

Likewise, Hindu dalits are considered to be below the caste system, and not part of human society. They cannot enter higher-caste Hindu temples, must use separate water supplies, are refused entry to the shops used by caste Hindus and are forced to live in separate communities. (Asian Human Rights Commission, 2002)

And some Nepalese are still held in hereditary slavery—known as bonded labor—by greedy landlords. Dipendra Chaudhary, a 20-year-old fighter with the CPN(M), explained his family’s position in society: “My family are all slaves, from the old times, from my ancestors. We lived in a very small hut. We were 10 and the landlords used to make us do everything. We used to prepare food for them and they used to kick us out because we were low class.” (Newsday, Aug. 14, 2005)

These unbearable living conditions have made the armed uprising popular especially among the peasants and young people.

The people’s movement

There is a rich history in Nepal of people fighting back against the country’s dire social and economic conditions. Marxist ideas have long been popular, permeating all castes and classes. The communist movement, inspired by the triumph of the Chinese revolution, has enjoyed strong support over the years.

The CPN(M) emerged from another communist organization in 1994. Shortly thereafter, it created the PLA to carry out a revolutionary war against the government. The revolutionary army initially numbered a few hundred, but it has since grown to more than 25,000, including local militias. (Outlookindia.com, Jan. 3, 2006)

Once the rebellion began, the country’s police unleashed a wave of violence and terror against the rural population. Peasants in conflict areas were deemed “Maoist supporters” and often brutally tortured and killed. With the aid of U.S. military “advisors” and millions of dollars, the Royal Nepalese Army quickly joined the battle, and the repression increased exponentially. The army has been cited as one of the worst human rights abusers in the world. (Nepal: Security Forces ‘Disappear’ Hundreds of Civilians, Human Rights Watch, May 1, 2005)

Despite these significant obstacles, the insurgents have gained much ground throughout Nepal. They currently control about 80 percent of Nepal’s countryside, with growing influence in the cities among the urban workers.

They operate an alternative government—what they call the People’s Republic of Nepal—in the parts of the country they control. These liberated areas consist of nine national and territorial autonomous regions. In these areas, the CPN(M) is building people’s committees and mass organizations and carrying out sweeping democratic reforms. The presence of the king’s government is “now limited to the capital, district headquarters and highways,” according to CPN(M) politburo member Pavrati. (People’s Power in Nepal, Monthly Review, Nov. 2005)

In areas under the control of the communists, people’s committees have formed, which are either nominated or elected, and oversee the administration of the regions. They are seizing land from corrupt officials and redistributing it to poor peasants. Oppressed minorities have the right to practice their own languages and culture. They also participate equally in the governing of the liberated zones.

Laws and historical social practices that discriminate against women, lower castes and dalits have been done away with. Women are given the right to divorce, inherit land, go to school and join local militias and the PLA.

In these liberated zones, courts independent of the monarchy have been established to settle disputes and to punish domestic violence and other crimes. An open-jail system is helping to facilitate the transformation of those convicted of crimes into productive citizens. An elaborate postal courier system has been constructed. Local militias have been created to ensure security and participate in public construction work in the liberated regions. These deep reforms have helped broaden support for the uprising in Nepal’s rural areas.

Challenges facing the movement

But difficult challenges lie ahead. The most immediate challenge is to topple the monarchy. To do this, the CPN(M) is attempting to consolidate greater support not only in the outlying rural regions but also in the cities. Although its presence in Kathmandu and the surrounding region is weaker than in the countryside, its student and women’s organizations are quite powerful in the city. (Counterpunch.org, Sept. 7, 2005)

The united front against the king signals a step forward. Whether or not the king is removed, the joint call for a constituent assembly, if realized, is likely to render his position meaningless. A constituent assembly is a representative body elected with the purpose of drafting, and in some cases, adopting a constitution.

But that demand also has its pitfalls. Most of the parliamentary parties, based in the cities, are oriented toward establishing a stable capitalist economy in Nepal. One of the main parliamentary parties, the Communist Party of Nepal (Unified Marxist-Leninist), also characterizes itself as communist. It held more than 31 percent of the seats in parliament and has substantial support among urban workers and some sectors of the youth. The party’s overall perspective, however, is parliamentary rather than revolutionary.

If the Nepalese bourgeoisie stabilizes its authority after the fall of the monarchy, the outcome could only mean continued dependence on the other world and regional capitalist powers like India and U.S. imperialism.

The seven-party parliamentary alliance that has now entered into a united front with the CPN(M) hopes that the united front will bring the CPN(M) into the political “mainstream”—a code phrase for a loyal opposition within a capitalist democracy. They seek to remove the monarch so that they can institute liberal reforms, while essentially running Nepal for the local bourgeoisie, the Indian bourgeoisie and the imperialists. They do not want the revolutionary forces to give the working classes real political power.

For its part, the CPN(M) says it does not want a return to politics-as-usual when the king is removed. It seeks what it calls a “New Democratic state” under the leadership of the proletariat. For them, the united front gives an opportunity to win more adherents among workers in the capital.

But if the constituent assembly eventually comes to pass, continuing the revolution beyond the democratic tasks and toward socialism will be another major test. That perspective will be bitterly opposed by the bourgeois forces in the assembly, allied with neighboring capitalist countries and the imperialists.

A related challenge facing the people is to break India’s and the imperialists’ hold on Nepal. Any new progressive or socialist-oriented government would have to worry about the possibility of military intervention from hostile neighboring and imperialist states.

The Indian ruling class opposes a change in Nepal’s structure because it fears losing the domination it has enjoyed over Nepal’s economy and politics for decades. It is also worried that a revolution in Nepal could spill over into its territory. There is a communist insurgency in India led by forces allied with the CPN(M).

The U.S. imperialists vehemently oppose a people’s victory in Nepal. U.S. ambassador James Moriarty has expressed the government’s worry that “Nepal is getting to the point where its very existence is at stake.” (Kantipuronline.com, July 25, 2005)

Since 2002, the CPN(M) has been listed by the U.S. government as a “foreign terrorist organization.” Meanwhile, U.S. aid is quietly funneled to Nepal’s king through third-country conduits. The United States also conducts joint exercises with the murderous army and supplies it with thousands of M-16 rifles, communication and night vision equipment, and training in counterinsurgency.

The Chinese government also is not keen on dislodging the king for reasons related to their own policy in the region. China has granted military aid to the Royal Nepalese Army in recent months. In addition, the Indian Express reported in November 2005 that Nepal purchased 4.2 million rounds of bullets, 80,000 grenades and 12,000 AK-47s from China.

Transforming society

For the insurgency to consolidate popular support and realize its ultimate goal of a socialist state, it must decisively break the bonds of economic exploitation.

The revolutionary reforms launched in the liberated regions of Nepal by the CPN(M) have done much to forward the social liberation of the people. They demonstrate concretely that people can shape their own destinies; that people do not have to live in unending poverty and misery. But until the revolutionaries are able to smash the state apparatus in Kathmandu and create a new state power based on the urban workers and rural peasants, the reforms are limited and socialist construction cannot begin on a truly nationwide scale.

Articles may be reprinted with credit to Socialism and Liberation magazine.