The 2002 election of Luis Ignacio “Lula” da Silva as president of Brazil poses an important question for revolutionaries: Can the electoral victory advance the class struggle in Latin America’s biggest economic power?

Lula won the elections with 61.5 percent of the vote. Voter turnout was 80 percent, reflecting mass enthusiasm for the former trade union leader. The world media fearfully labeled Lula as the “first working-class president” in Brazil’s history, while the masses of Brazil and across Latin America rejoiced over the electoral victory of a popular leftist candidate.

Neither Lula’s Workers’ Party (PT) nor his election campaign was particularly radical. But many in the progressive and working class movements in Brazil and the world viewed his election as a victory. João Pedro Stedile, the national leader of the Landless Workers Movement (MST), said just before Lula’s election, “The PT adopted an electoral tactic that is not left. … But I believe that Lula’s victory will represent a symbol for depoliticized people, who will find they have come into their own and will rise up. Hence, a victory for Lula could stimulate a new rise of the mass movement in Brazil that has been in retreat for more than 10 years.” For the masses, Lula’s victory also signified hope for an end to the brutal, violent free market ‘reforms’ of his predecessors.

Brazil is the most populous country in Latin America with 184 million people. The country has the largest Black population outside of Africa — half of the population, by some estimates. Despite the claims by some that Brazil’s society is free of racism, a disproportionate share of the official 22 percent of the population living in poverty are Black, and the Brazilian ruling class is white.

The country has the largest economy in the region, accounting for nearly 40 percent of Latin America’s combined gross domestic product. It has a developed industrial base and a huge amount of natural resources. The Brazilian bourgeoisie increasingly aims at becoming an economic force in Latin America with its dominant position in the MERCOSUR common market, a trading alliance between Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay and Uruguay.

Unemployment in Brazil has risen steadily to its current level of 12 percent. This, combined with the budget cuts initiated by former president Fernando Cardoso at the behest of the Inter-national Monetary Fund, has generated growing pressure for change.

This is why the U.S. and Brazilian ruling classes feared Lula’s electoral victory. But they also knew perfectly well that Lula and the Workers’ Party were willing to make major concessions in an effort to appease the world’s bankers. The PT had appointed Jose Alencar, CEO of the textile conglomerate Coteminas and a member of the ruling class Liberal Party, as Lula’s running mate.

Still, the Brazilian ruling class and U.S. imperialists feared the rising tide of popular mobilization that was behind Lula. They feared the raised expectations of the Brazilian masses.

To this end, the Brazilian ruling class has garnered its forces in an effort to demonize and demoralize the social movements that gained momentum with Lula’s election. Rural landowners still organize state and local militias to brutalize the Landless Workers’ Movement.

Pressure from the ruling class

At the same time, the Brazilian capitalist class is pressuring Lula to stay closely within the confines of economic programs dictated by Wall Street. Most importantly, Lula has been unable or unwilling to break with the domination of the International Monetary Fund over Brazil’s economy, even as he calls for softer terms from the IMF. In December 2003, PT congresspeople helped push a plan to privatize the country’s pension system.

The continued power of the ruling class to attack the mass struggle and gain concessions from Lula’s government illustrates the fact that while Lula’s electoral victory was a morale boost for the Brazilian working class, it did not shift the balance of power in society. The working class did not take state power when Lula won the presidency. It does not control the means of production, the media, the judiciary, or the military and police.

In the arena of foreign policy, Lula has also raised hopes among progressive people. His refusal to bow to U.S. hostility toward the unfolding revolutionary process in Venezuela and toward socialist Cuba continues to provoke ire, prompting right wing U.S. Congressperson Henry Hyde to dub Lula, Fidel Castro and Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez a Latin American “axis of evil.”

Even here, though, Lula’s government caved into the U.S. pressure by announcing its takeover of the military occupation of Haiti in June under the banner of the United Nations. This decision came after the U.S. consistently undermined the democratically, popularly elected government of Jean-Bertrand Aristide in Haiti.

Continent-wide relevance

This question of how the working class can take advantage of electoral victories is being posed across Latin America. The inability of traditional political elites to impose IMF economic policies, combined with growing mass struggles, has resulted in the elections of Hugo Chávez in Venezuela and Lucio Gutierrez in Ecuador. While the Chávez election has opened a revolutionary process, Gutierrez has betrayed the masses who elected him.

Since 1883, when the U.S. declared Latin America its “backyard,” people have been engaged in some form of resistance against the U.S. ruling class’ attempts to politically, economically and militarily control Latin America.

The U.S.—either by direct intervention, support for brutal military dictatorships or both—crushed many of the anti-imperialist social movements from the mid-1950s through the 1970s, such as in Chile after 1973. This left the social movements disorganized and leaderless, but the conditions that gave rise to these social movements worsened and the struggle continued. Many of the movements and uprisings have lacked leadership, like in Argentina in 2001. Others oriented toward the electoral struggle, like in Brazil in 2002.

As the experiences in Brazil have shown, electoral victory in any country must be recognized as only an increased possibility for the working class—not as the victory of state power. This possibility can only be realized in the mobilization and organization of working and poor people and their allies to establish power over the means of production and the state apparatus.

In the face of the vacillations of the Lula government and the machinations of the ruling class, the real hope for the class struggle in Brazil remains the social movements. Ninety percent of Brazil’s land is owned by 20 percent of the population, while the poorest 40 percent of the population own just 1 percent. Some 50 million of the country’s 175 million people live in poverty.

Growing opposition

On June 7, Lula’s vacillations provoked the latest in a series of splits in the PT. The new Socialism and Liberty Party (PSOL) plans to challenge the PT in the upcoming elections. “Our mission is to hold aloft the fallen banner of the original Workers’ Party,” former Senator Heloisa Helena told the Associated Press. “We are for land reform, higher wages and labor rights, while we oppose agreements with the IMF and the U.S.

“We will seek support from labor unions and social movements everywhere in Brazil,” she continued. “We will accept support from anyone except capitalists, opportunists and racists.”

The MST represents 4 million of Brazil’s poorest peasants and is responsible for the takeover and successful occupation of thousands of acres of unused land in Brazil.

The MST supported Lula’s election campaign and victory. It now charges that Lula’s government has moved too slowly to address the needs and demands of the landless workers.

The MST has begun a campaign to step up pressure for land reform. In March, peasants seized 50 estates and began working the estates themselves. During the first week of April, MST leader João Pedro Stedile called for the movement to set Brazil “ablaze” with protest, provoking panicky reports in the newspapers from Brazil’s elite and foreign investors.

The union movement has also mobilized. On May 1, over 2 million workers demanded that Lula combat unemployment in a protest in São Paulo called by the two largest union federations. And, on June 16, over 5,000 people protested proposed labor reforms in Brasília.

Lula has responded cautiously, trapped between the interests of those who elected him and the interests of the domestic and international agribusiness and industry concerns whose state he serves.

“At the rate at which the government is working, our goal will never be reached,” UPI quoted MST regional leader Claudiomir Viera saying on April 7. “We have to take over the land.”

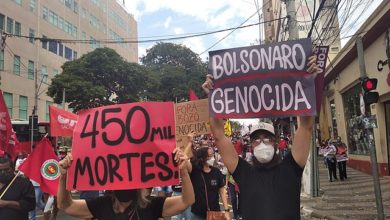

Recent demonstration in Brasilia against President Lula’s labor and economic reforms.