On Dec. 16, the Federal Reserve—the U.S. central bank, and under the dollar system the world’s central bank—announced an increase in its “policy rates” of interest, the first since before the Great Recession. These rates include the rate at which commercial banks lend reserves to one another overnight (the federal funds rate) and the discount rate (for lending to commercial banks by regional Federal Reserve banks). The decision by the Fed’s Open Market Committee brings these rates more into line with rising money market rates.

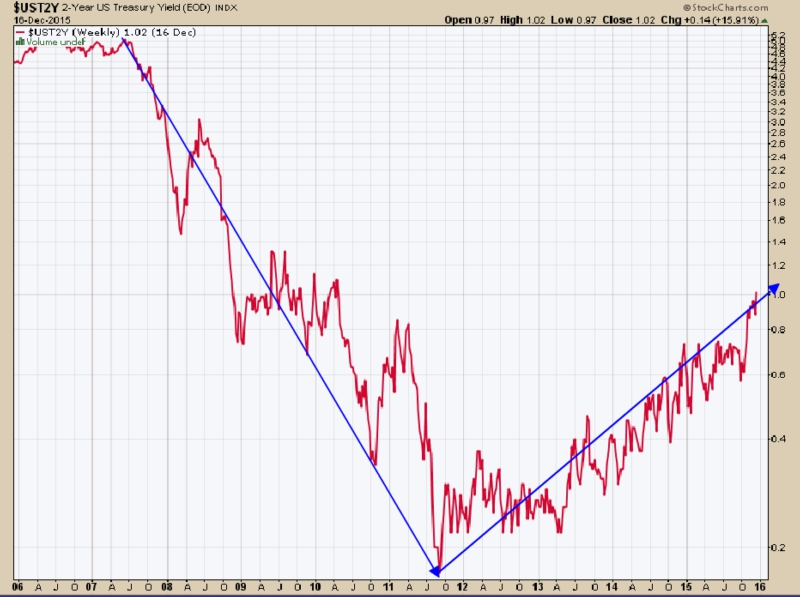

Money market rates have been in an uptrend since mid-2011, about two years after the initial recovery from the devastating Great Recession got underway in 2009. For example, the interest rate on two-year Treasury notes has risen from barely above zero to about 1 percent currently. (See chart below.)

Despite the widespread belief that the Federal Reserve controls interest rates, the fact is that the Fed typically sets its policy rates to follow, in stair-step fashion, market-based rates down when those rates are declining, and follow them up when they are rising, with a lag in each case. The money market rates fluctuate in accordance with the capitalist industrial cycle—falling sharply during an overproduction crisis and subsequent depression phase and rising after a recovery gets underway, as shown by the above chart.

Fed unusually cautious

This time the Fed waited an unusually long time to raise its policy rates, worried that the sluggish recovery would be aborted if it acted “too soon.” Moreover, the increases are small—for example, only 0.25 percent for the Federal Funds rate (from 0.0-0.25 percent to 0.25-0.50 percent) and the same for the discount rate (from 0.75 to 1 percent).

Commercial banks have followed suit, raising their “prime rate” (offered to the most credit-worthy customers) as well as credit card, auto loan and other rates.

Although the Fed normally follows but doesn’t set money market interest rates, it does control its “monetary base,” the paper dollars it prints and digital dollars it creates electronically. The resulting “bank reserves” over and above the minimum required to back up deposits of commercial banks provide the basis for new lending by those banks. Most of what is called “the money supply” is created by such lending activity (via credit cards, auto loans, house mortgages, student loans, and so on) and shows up as bank deposits, mere accounting entries, called by economists credit money.

The Federal Reserve Open Market Committee controls the Fed’s policy rates by expanding or contracting the size of its monetary base, mainly through its “open market operations”—hence the name of the committee—buying and selling securities. If it decides to raise policy rates, like it has just done, it must contract the monetary base (by selling securities from its holdings). When later it wants to reduce its policy rates, it will need to expand the monetary base (by purchasing securities).

‘Quantitative easing’

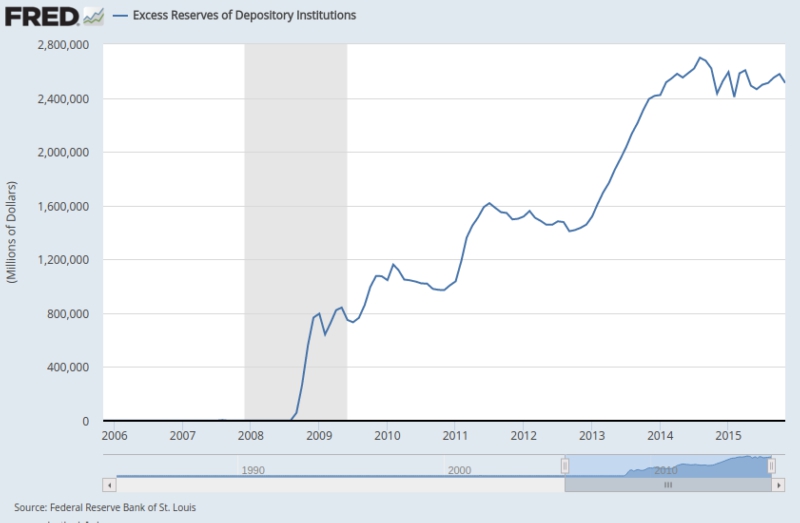

Normally, the Federal Reserve’s open market operations involve short-term (mostly government) securities. However, because the entire banking system teetered on the verge of collapse during the Great Recession, the Fed was forced to expand these operations to long-term government and mortgage bonds—called “quantitative easing.” As part of bailing out the “too-big-to-fail” banks, the Fed purchased huge quantities of these bonds, paying for them by crediting the banks’ accounts with the Federal Reserve, thereby greatly augmenting the banks’ reserves and therefore the Fed’s monetary base. As a further gift to the banks, the Fed agreed to pay 0.25 percent interest on the humongous bank reserves, now raised to 0.50 percent.

The following chart shows the unprecedented increase in “excess reserves”—starting from the “normal” level of close to zero in 2008 and preceding years—that resulted from three rounds of quantitative easing, each round followed by a pause reflected in the decline or leveling off of the amounts shown in the chart. The Fed ended its third round of QE last year, and the excess reserves initially declined but then leveled off at about $2.5 trillion ($2,500,000,000,000).

The pauses shown on the chart actually represent monetary tightening by the Fed, even though it didn’t raise its policy rates, until now. Each pause in the face of continued, if sluggish, economic expansion meant that short-term interest rates would rise—as in fact happened, as shown in the first chart above.

The pauses shown on the chart actually represent monetary tightening by the Fed, even though it didn’t raise its policy rates, until now. Each pause in the face of continued, if sluggish, economic expansion meant that short-term interest rates would rise—as in fact happened, as shown in the first chart above.

The Fed’s big gamble

The latest move by the Fed further tightens credit, since it will require a further contraction of the monetary base to implement. If the economic expansion continues, that will inevitably mean a renewed rise in market interest rates, which in turn will require the Fed to raise policy rates again, and again.

A Credit Suisse research note issued after the Fed’s rate hike stated: “In some ways, it seems odd that the Fed would increase interest rates in the current circumstances. Commodity prices have collapsed, credit and emerging markets are showing distress, and our measure of global risk appetite is hovering near ‘panic’ levels. On top of that, ISM [Institute of Supply Management] headline and new orders have fallen below 50 for the first time in three years and US industrial production has contracted in eight of the last eleven months.”

In its statement, the FOMC sought to reassure the financial markets by saying that it expects the ensuing rate increases to be “gradual”—in small increments and spaced out. This means the Fed expects (really, hopes) market-based rates—determined not by the Fed but by economic developments beyond its control—will rise only gradually.

The Fed’s move suggests the recovery will continue and a new boom phase of the industrial cycle will get underway in the not too distant future, followed at some point by a new overproduction crisis—though as always the Fed hopes (but will fail) to avoid such a crisis. An extended recovery is by no means certain, however, as hinted in the Credit Suisse research note. There are many signs of a slowdown of the global economy happening now, with some economies—notably Brazil but others as well—falling back into recession.

The countries hardest hit are exporters of primary commodities such as oil and natural gas, copper, platinum, palladium and iron ore. The prices of such commodities, which are priced in dollars, have plunged in the face of the pause in the growth of the dollar monetary base following the third round of quantitative easing. Oil, for example, has collapsed from well over $100/barrel in mid-2014 to around $35 currently.

Since most oil-producing countries—for example, Russia, Venezuela, Iraq and Saudi Arabia—depend on oil exports for a large portion of government revenue, and most of the big oil producers in these countries are state-owned, the response to falling prices is at first to increase, not decrease, production. This pushes prices down further in a deflationary spiral.

That has been bad for one sector of the U.S. economy, the rapidly growing fracking industry, but has been beneficial for most other sectors, acting like a big tax cut for businesses and consumers alike. The net result for the U.S. has been positive so far, which made possible the latest Fed tightening move. However, further declines elsewhere in the world could bring a premature end to the current expansion.

‘Junk bonds’ fiasco

Another risk to the economy is a collapse of the high-yield—so-called junk—bond market. Many of these bonds, floated to finance exploration and production of oil in the fracking sector, are already in steep decline. The following chart shows the steep decline in the share value of a prominent junk bond fund from its peak earlier this year.

Banks, hedge funds and other financial institutions invested in junk bonds for their high yields and now face defaults and heavy losses. One major mutual fund, Third Avenue Focused Credit Fund, recently went belly up due to a panicky wave of redemption requests by shareholders that it could not meet. This disastrous run on the fund occurred despite a $200 million cash reserve built up in the days before its collapse.

Banks, hedge funds and other financial institutions invested in junk bonds for their high yields and now face defaults and heavy losses. One major mutual fund, Third Avenue Focused Credit Fund, recently went belly up due to a panicky wave of redemption requests by shareholders that it could not meet. This disastrous run on the fund occurred despite a $200 million cash reserve built up in the days before its collapse.

A further major default on debt is looming, and that is the $2 billion in debt payments coming due at the end of this year owed by the U.S. colony of Puerto Rico. It’s bonds, which paid exceptionally high interest, are owned by a wide spectrum of financial institutions, including hedge funds, mutual funds and even pension funds.

Congress failed to pass legislation granting Puerto Rico the right to declare bankruptcy and go through an orderly, if highly unjust, process for getting out from under its debt burden like Detroit did. Therefore, this could end up in a disorderly default that could further rile the financial markets.

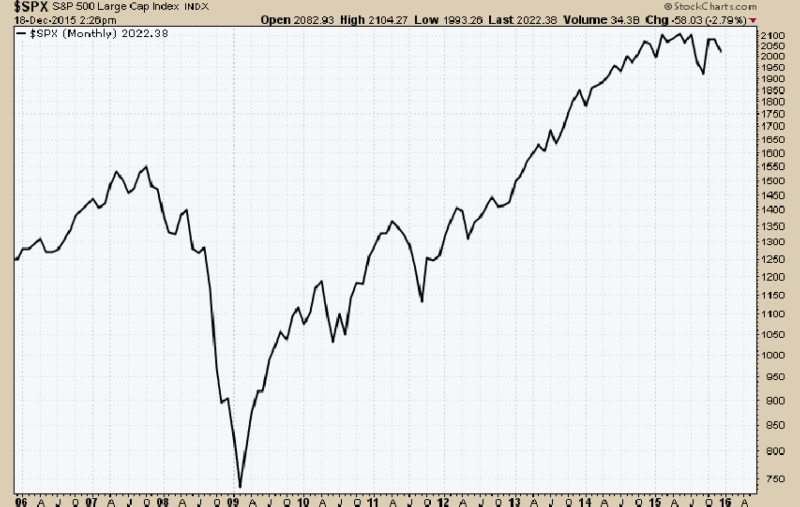

Another danger is a stock market correction that turns into a crash. As a result of years of super-low interest rates, along with massive stock buybacks by corporations, share values have soared since the market hit bottom in 2009. (See following chart.) Now with the prospect of rising interest rates, these levitated share prices could turn down—possibly with a vengeance as panicky investors rush for the exits at the same time.

If all or some combination of these losses start a serious contagion that threatens the big banks, the Fed may be forced to reverse course and begin a fourth round of quantitative easing—and on a massive scale. But that would risk a new run on the dollar, such as began in late 1979 and early 1980, before the sky-high interest rates of the famous Volcker Shock saved the currency from total collapse. Since a strong dollar is crucial for the continued dominance of the U.S. empire, ensuring that status has the highest priority for U.S. finance capital.

If all or some combination of these losses start a serious contagion that threatens the big banks, the Fed may be forced to reverse course and begin a fourth round of quantitative easing—and on a massive scale. But that would risk a new run on the dollar, such as began in late 1979 and early 1980, before the sky-high interest rates of the famous Volcker Shock saved the currency from total collapse. Since a strong dollar is crucial for the continued dominance of the U.S. empire, ensuring that status has the highest priority for U.S. finance capital.

Socialist planning and regulation must replace capitalist anarchy

The conclusion is inescapable: The glory days of capitalism in general and the U.S. empire in particular are receding into the past, never to return. The system has reached the point that the most basic needs of major parts of society are going unmet or in serious jeopardy—especially in the oppressed countries but increasingly also in the “advanced countries.”

Wars multiply and escalate. One country after another is torn apart, its infrastructure and institutions destroyed. Austerity bites ever deeper. Climate change threatens the livability of the planet for many species including our own. Mass unemployment and poverty spread. Policy brutality and mass incarceration (along with surveillance) reach unprecedented levels. Racism is on the rise, and fascism has raised its head. The capitalist system has to go.