This article is part of Liberation’s commemoration of Black History Month, 2021.

During Black History Month each year we recognize leaders who have pushed the struggle forward with events, memorials and educationals. Many of those we celebrate believed in and fought for revolutionary change.

Prior to the Emancipation Proclamation on Jan. 1, 1863, the Union was losing the Civil War. But that summer, the bloodiest battle of the Civil War — the Siege of Port Hudson, in which more than 15,000 perished just north of Baton Rouge — resulted in a turning point for the North by blocking supplies and support from the richest state of the Confederacy, Texas. In this siege lasting 48 days, a great hero, Andre Caillioux, the first Black officer of the Union army, was killed on the seventh day of the battle. His body lay on the ground for 41 days.

Andre Cailloux

Not widely known, and certainly not celebrated enough, Andre Cailloux was the first Black military hero functioning as an officer in the Union Army. Robert Smalls, who in 1862 commandeered the CSS Planter from Charleston harbor, freeing himself, his family and crew and escaping through Confederate controlled waters, is often cited as the first Black Civil War hero prior to Blacks being recruited into the Union Army.

Born in Plaquemines, La., Andre Cailloux lived in what is today the 3rd Ward of New Orleans. He was widely known as a seasoned boxer who certainly must have used his skills to train his troops in hand-to-hand combat on the battlefield where he perished in the first storming on the Confederate stronghold.

Cailloux, like other free men of color, was conscripted into the Confederate Native Guard which had to appear for troop review although without uniforms or arms at various times in 1861 and 1862. Under the eyes of the masters, these events became celebrations in the Afro-Creole community of New Orleans. Like social control measures today, the repressive environment created by the slave owners was used to police the Afro Creoles where their few privileges were maintained only by constant public expression of loyalty to the system. However, those in this class like Cailloux, a cigar maker, used these gatherings as opportunities to organize. At this time, Andre Cailloux rose as a leader and organizer, ultimately taking these regiments to fight for the Union at Port Hudson.

Imagine the precarious position of the Afro-Creole community in New Orleans at the time. It numbered approximately 11,000 people in a city of 100,000. Many had become so-called free men of color after purchasing their freedom as in the case of Cailloux; his wife Felicie also became free when her mother purchased her freedom along that of two other siblings.

The system of slavery in the region from the various colonial powers created a subset of free people who could potentially be helpful to the colonial powers. The colonial powers attempted to give these free men of color just enough privilege to drive a wedge between them and those in full bondage. But that plan didn’t work and among the Afro-Creole communities, leaders emerged, participating in many significant military battles. The long-standing struggle for higher education for Blacks predated the Civil War and was implemented by the first and only Black governor of Louisiana, P. B. S. Pinchback. Southern University today is part of that initiative.

The struggle for control of the Mississippi River was a main feature of the Civil War. The Union victory of the siege also meant control of the Red River, cutting off East-West Confederate supply routes. By controlling Port Hudson, the Union effectively took control of the Mississippi. The Union was attempting to defeat other Confederate strongholds in the region.

From Native Guard to Union officer and hero

As the Civil War started and continued, the Afro-Creole community in New Orleans faced economic hardship. Cailloux even had to sell his home.

It was during this time that Cailloux earned the reputation of saying he was “the Blackest man in New Orleans.” This slogan reverberated perhaps in the same way that Kwame Ture’s (birth name Stokely Carmichael) “Black Power” did decades later: rallying those oppressed by highlighting self love, a sense of nation and the need to build and take power.

After the Union occupation of New Orleans in April 1862, the Native Guard regiments were disbanded. Later that summer, General Order 63 was announced, allowing for the regiments to re-form under the Union pending approval by the president — six months prior to Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation. Within the next two days, nearly 100 businesses of free men of color closed as men rushed to enlist.

Cailloux’s funeral and inspiration

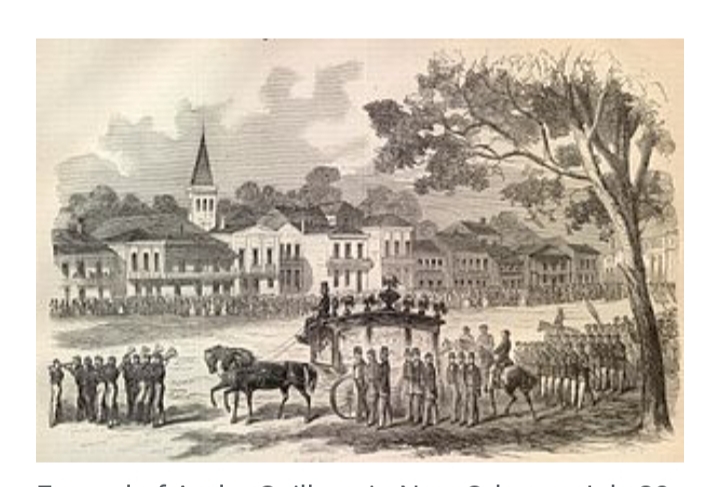

Although photography was available during the Civil War, newspapers had no way to print photographs, so often artists would draw renditions of the spirit of events. Above is a depiction of Black troops charging the Confederate earthworks in the Battle of Port Hudson. Earthworks were a type of elevated trench that’s suitable to the terrain of Louisiana. The artwork portrays the charge forward and valor of the Black troops. This was some of the bloodiest warfare of the Civil War and had the highest number of casualties, especially among Black troops.

After the battle was over and Cailloux’s body was recovered, barely recognizable except for a ring on his hand, historian Steven Ochs writes that no funeral compared since the first Confederate procession earlier in the war.

“Eight soldiers, escorted by six black captains and six members of the Friends of Order, brought the casket on their shoulders from the hall. Two companies of the 6th Louisiana (colored) Regiment acted as an escort while representatives of more than thirty black male and female mutual aid, fraternal, and burial societies, many of which Maistre had helped organize, lined Esplanade Avenue for more than a mile, waiting for the hearse to pass.”

“If ever patriotic heroism deserved to be honored in stately marble or in brass that of Captain Caillioux deserves to be, and the American people would never redeemed their gratitude to general patriotism until that debt is paid,” recorded an account in 1890.

The “Maistre” referenced by Ochs was Father Claude Pascal Maistre, a French-borne priest and ardent abolitionist who was ostracized by the Catholic Church. He presided over Cailloux’s funeral under censure for his abolitionist views and for advocacy for Blacks to join the Union to smash the slavocracy. Cailloux’s funeral, that of a lieutenant sergeant in rank, was widely covered in the northern press including the New York Times, New York Herald and Harper’s Weekly, not to mention the Afro-Creole L’Union.

The important point is that leaders and those who will be the best fighters will come from the working and oppressed people in the next revolution to finally complete all the past unfinished revolutions for true liberation. We must remember them during this Black History Month as the spirit of struggle is in the air.

Sources:

Ochs, Stephen J. (2006). A Black Patriot and a White Priest: André Cailloux and Claude Paschal Maistre in Civil War New Orleans (Conflicting Worlds: New Dimensions of the American Civil War) LSU Press.

Rogers Albert, Olivia V. (1890) The House of Bondage. Cosimo Classics.